During my visit to Abu Dhabi in early December 2025, I visited the new Louvre, which is being promoted as a “new interpretation of the universal museum concept“.

I booked a one-week holiday package with my local carrier Luxair, and I stayed at Hotel Beach Rotana (see my review).

I also visited (and reviewed):-

First Steps

The very first step was to decided which were the most important sights to see in Abu Dhabi, and the list was surprisingly long.

I finally decided on three different sites, and the first one was the Great Mosque, and this, the second, was the Louvre Abu Dhabi, a unique cultural partnership between the UAE and France.

On their website I pre-purchased a ticket for a specific day. Not sure where I read that this was advised because there was a limit on daily access. When I arrived there were people queuing to buy tickets, but when I left there appeared to be people waiting to access the museum.

There is no strict official dress code, but because the museum is a major cultural institution, visitors are expected to dress modestly and respectfully. But as far as I know there’s no official requirement to cover shoulders, hair, or wear formal dress.

Introduction

The musuem was conceived to be more than a satellite of the Paris Louvre. It aims to offer a global narrative of human creativity, bringing together artworks and artefacts from across civilisations and to explore shared themes of human history and culture.

Designed by Pritzker Prize–winning architect Jean Nouvel, the museum is itself an artistic statement. A dramatic 180-metre perforated dome with 7,850 geometric stars appears to float above a “museum city” of low-lying galleries and plazas.

I must admit I was very impressed by the dome, but had not realised they were stars.

Location

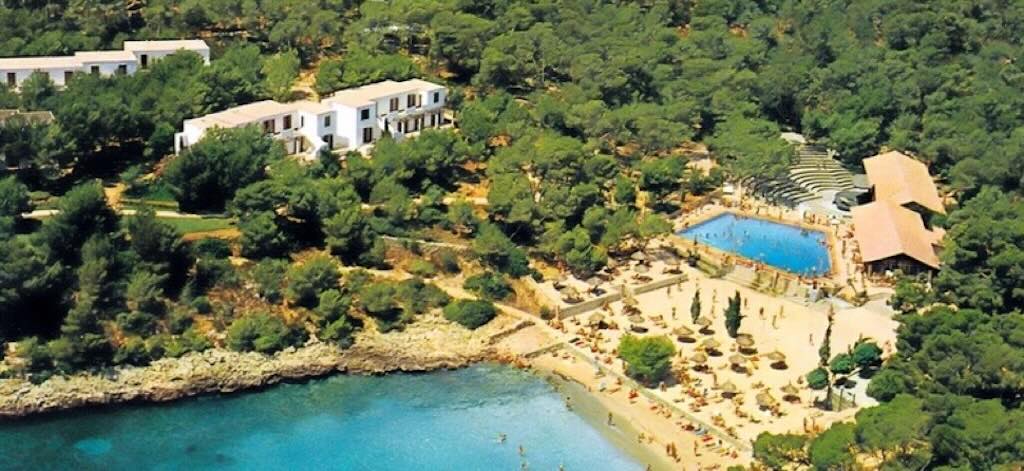

The museum is located in the Saadiyat Cultural District, which is part of Abu Dhabi’s wider strategy to position itself as a global destination for art, history, science, and cultural exchange.

Manarat Al Saadiyat is a long-established cultural centre, predating the big museum boom, serving as a community hub for contemporary art exhibitions.

teamLab is a interactive digital art museum.

There is a Natural History Museum which is the largest natural history museum in the Middle East.

Zayed National Museum is dedicated to the heritage, culture, and history of the United Arab Emirates.

The Abrahamic Family House is an interfaith complex housing a mosque, a church, and synagogue.

And there is under construction a Guggenheim, a contemporary art museum designed by Frank Gehry.

The below map is slightly out of date, because in 2021 The Natural History Museum Abu Dhabi was announced (it opened in Nov. 2025). It now sits between teamLab and the Louvre. However, the Performing Arts Centre Abu Dhabi has not yet been built. Unlike the plan for a future Maritime Museum, which has been cancelled, the Performing Arts Centre (originally designed by Zaha Hadid) has been simply “reprioritised”.

Louvre Floor Plan

Despite the dome being a major attraction in itself, the entrance to the museum, doesn’t really play to that. And in fact, the visitor will only discover the dome near the end of their visit.

Below, I’ve copied the guide showing the 12 galleries that make up the core of the visit.

Gallery 1 The First Villages — early human settlements.

Gallery 2 The First Great Powers — emergence of early states.

Gallery 3 Civilisations and Empires — interactions between flourishing civilisations.

Gallery 4 Universal Religions — development and spread of major faiths.

Gallery 5 Asian Trade Routes — long-distance exchange and cultural connectivity.

Gallery 6 From the Mediterranean to the Atlantic — early global encounters.

Gallery 7 Thinking the State — ideas of governance and society.

Gallery 8 Early Modern Globalisation — widening global connections in the early modern era.

Gallery 9 A New Art of Living — cultural responses to changing lifestyles.

Gallery 10 A Modern World? — modernity and its beginnings.

Gallery 11 Challenging Modernity — critical engagements with modern ideas.

Gallery 12 A Global Contemporary — concluding reflection on the shared human story.

The Collection

In Gallery 1 I found “Monumental statue with two heads”, dated to ca. 6500 BC (Pre-Pottery Neolithic). This is a large plaster bust, originally part of a group of human figures discovered at Ain Ghazal (Jordan) in the 1980s. We have two human heads fused onto a single torso, facing forward, with eyes inlaid with bitumen, giving a dark, striking gaze. They are not carved but modelled with lime plaster built up over an internal armature of reeds and twigs. Also many of these figures were carefully buried, suggesting ritual deposition rather than casual disposal.

It’s known that the people in Ain Ghazal were already practising early agriculture and animal domestication. They built permanent architecture, and had developed a complex ritual behaviour.

Most scholars think the statues had a ritual or symbolic function, possible linked to life/death or just male/female. The fixed, wide eyes might suggest watchfulness or guardianship.

The Dead Sea is one of the world’s most famous natural bitumen sources, exploited continuously from prehistory onward. To make these eyes the bitumen would have been heated to soften, and applied warm, then allowed to harden. This strongly suggests, controlled fire, thermal knowledge, and intentional manipulation. In any case lime plaster itself requires fire, because producing plaster involves heating limestone to create quicklime.

Looking at the heads I felt that there was a touch of Modernist Primitivism (roughly 1905–1935). Maybe Brâncuși in the way he focussed on archetype heads and not likeness, some said he had a “Neolithic restraint”.

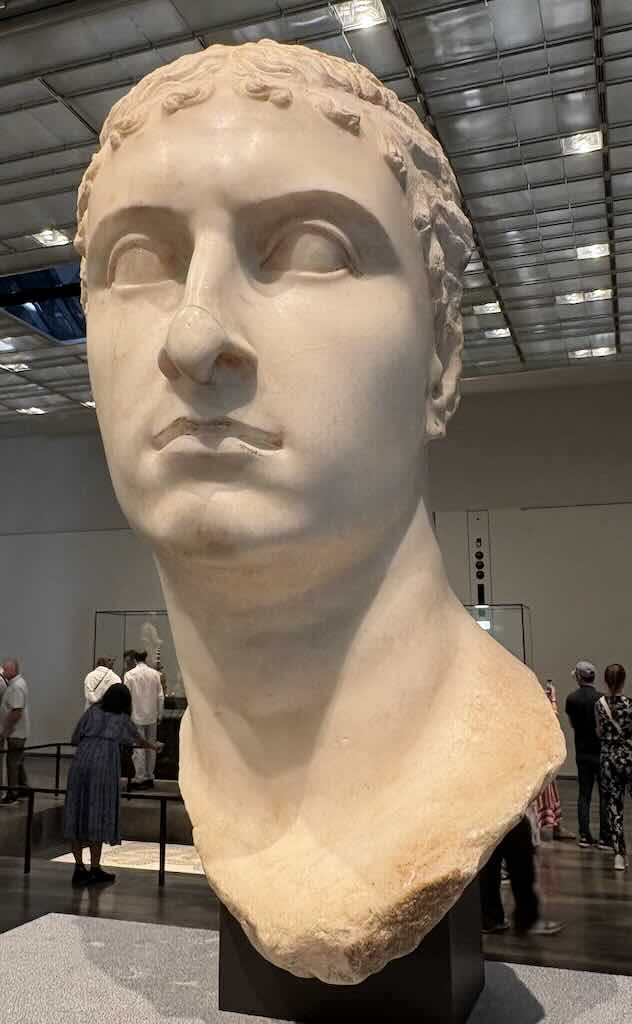

Here is a challenge. Before we hazard a guess who this might be, let’s collect some information.

This head is almost 70 cm high, so it must have belonged to a colossal statue, estimated 3.5–4.5 metres tall (and might have been seated or standing).

It was acquired at some point into the Louvre Abu Dhabi collection (through the museum’s acquisitions or loan arrangements), but no archaeological provenance (site or discovery date) is published.

The museum frames it as likely produced in Alexandria or the Egyptian royal workshops which were among the most important sculptural centres of the Mediterranean during the Ptolemaic period (305–30 BC). We must remember that Alexandria was one of the largest cities in the ancient world, a court city with continuous royal patronage, and home to state-funded workshops. Workshops that combining Greek/Roman portrait realism with Egyptian monumental/divine traditions (linking rulers to gods such as Isis). Ancient literary sources (Strabo, Pliny) and archaeologist agree that Alexandria had a distinct school of sculpture, comparable in importance to Pergamon, Rhodes, or Athens.

Some queens, including Cleopatra VII ruled as a king, not a consort, and Ptolemaic female portraiture deliberately adopted male-coded power, with a total lack of femininity.

In addition the museum also explicitly states the portrait incorporates features of the goddess Isis. Who was also usually presented as timeless, androgynous, non-sexual. This produced faces that modern viewers often read as masculine.

In the Ptolemaic period, the expression of female power, required a stern expression, to emphasise strength and authority.

But if you look carefully there are holes for attaching earrings, and there is a pinhole at the top suggesting a crown once sat there. And I’m told that the isiac curls (a hairstyle element associated with Isis) and headband are described as attributes of a deified queen, shared between Isis and Ptolemaic queens.

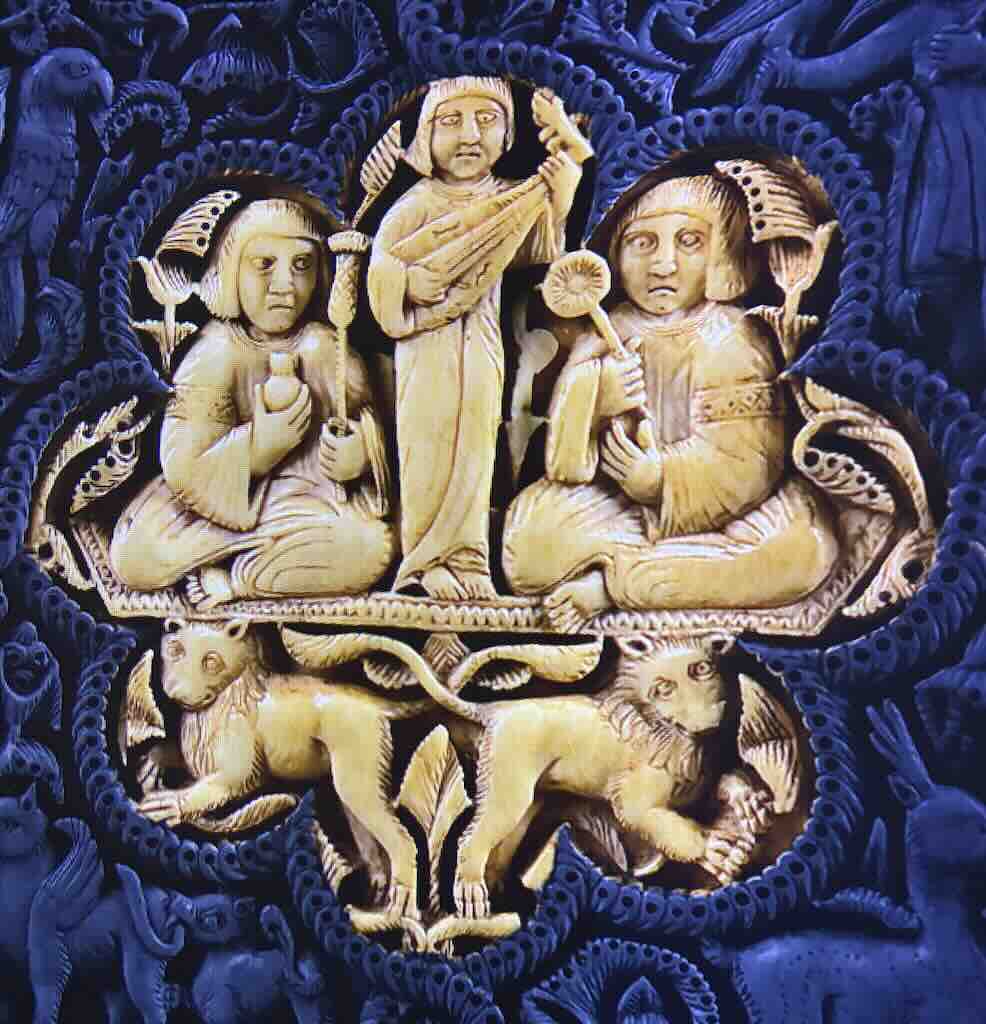

Above we have a Pyxis made for Prince al-Mughira (dated to 968). It’s roughly 15 cm by 8 cm, typical for Andalusian elephant ivories. It was made as a two-part object, a cylindrical body, and a tight fitting lid. In al-Andalus and the wider Islamic court world, ivory pyxes were used to contain perfumes (especially musk, ambergris, rose), aromatics and unguents, and occasionally medicinal compounds (or even jewellery).

The blue is not real, and is used here to highlight the three figures. The central figure stands slightly elevated, flanked by two seated figures. Each of the two flanking figures holds a staff or sceptre-like object. Beneath them are two animals, usually identified as lions, facing outward. This type of high-relief carving, was characteristic of Umayyad court workshops in Córdoba.

Lions in Andalusian court art symbolise royal power, dominance, and legitimacy. The three men are dressed in courtly garments, so a dynastic scene, not a narrative or religious one. Some experts suggest that the standing figure is a symbol for dynastic authority. The two seated figures are not equals in power to the central figure, suggesting competition, not cooperation (they are asserting a claim). In fact this pyxis was made for a young prince who was later murdered because he was a dynastic threat. It must be said that the Wikipedia article on this medallion offers a few different interpretations.

The museum text tells us that with the fall of the Umayyad dynasty and the establishment of the Abbasid Caliphate in 750, a descendant of the last Umayyad caliph seized Córdoba in 756 and founded an independent emirate, which soon expanded over a large part of the Iberian Peninsula.

Later in 929, Abd al-Rahman III proclaimed himself caliph. To consolidate his authority and affirm his new title, he founded a new capital city, Madinat al-Zahra, near Córdoba (see my visit report of Madinat al-Zahra). This city served as a significant administrative, commercial, and cultural hub. The flourishing artistic environment of this period included the production of precious objects made of textiles and ivory within the royal workshops. The Pyxis of al-Mughira, displayed in this gallery, stands as a testament to this artistic prosperity.

This pyxis was made in 968, under the reign of Caliph al-Hakam II, the son of Abd al-Rahman. The box was presented as a gift to Prince al-Mughira, the caliph’s half-brother, probably by their mother. At that time, the political climate at the court was unstable, with two main factions emerging, one led by the prince’s mother and the other by the caliph’s spouse. Some of the scenes depicted on the pyxis can be linked to this tumultuous context.

However, due to its iconography, the object is now considered as an auspicious gift designed to bring about the prince’s happy destiny. Nevertheless, to prevent him from seizing power, he was assassinated by his opponents in 976, shortly after the death of Caliph al-Hakam.

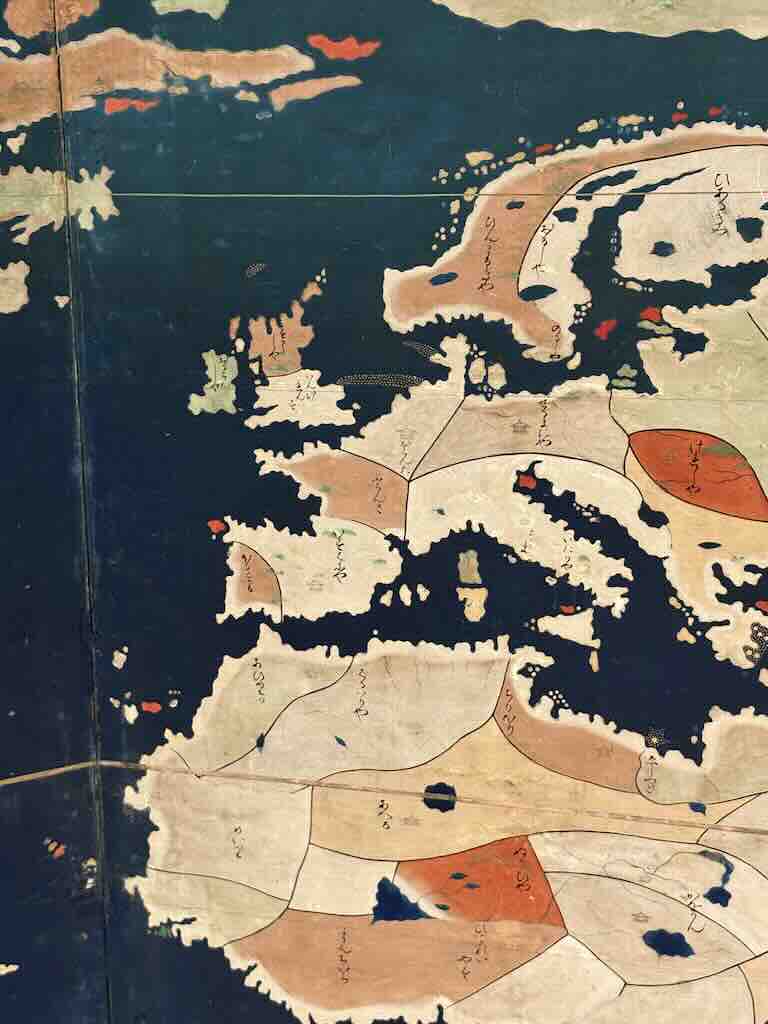

This is a small part of a Japanese folding screen with maps of the World (data ca 1690).

What attracted me was the odd shapes given to the British Isles. But perhaps more amazing is that in Japan around 1690, they could draw a map of the British Isles, including not only the separation of the United Kingdom and Ireland, but also including the islands of the Hebrides, Orkney, Isle of Man, and even a hint of the Shetlands.

This was a time when Japan and the world was changing more rapidly. Between the 16th and 18th centuries, the movement of goods, people, and ideas expanded dramatically across continents, reshaping societies, territories, and systems of knowledge. It shows that Japan, though politically regulated in its external contacts, was not isolated. Foreign objects, information, and visual models entered the archipelago through carefully controlled channels, contributing to new ways of imagining the world beyond its shores.

Cartographic folding screens, combined geographic information with decorative refinement, found a place in elite interiors. The use of ink, colour, and gold situates the maps within Japanese pictorial traditions while accommodating foreign spatial concepts and place names.

Displayed in domestic or ceremonial settings, such screens functioned as both objects of knowledge and instruments of display. They testify to a period when distant lands inspired fascination and curiosity, and when artists and craftsmen reinterpreted global change through local techniques and aesthetics.

We know virtually nothing about the maker of these folding screens (no signature, seal, or workshop mark). It’s dated based on cartographic conventions, and a stylistic comparison with other known world-map screens.

Almost certainly it belong to an elite Japanese household, possible a high-ranking merchant family. Such maps were status objects, not navigational tools, and ownership would have implied intellectual curiosity and worldliness rather than an experienced traveller.

The exact acquisition path (previous owner, auction house, or dealer) is not fully published in open catalogues.

It’s interesting that in European imperial cartography, maps were presented spread out on walls. The aim was often to support ideas of total understanding, mastery and even conquest. But these Japanese screens were more decorative than factual, and would have only been partially visible. They were made to be looked at, not used. Were they deliberately composed so that no viewer could ever fully “master” the world they depicted?

This is “The Rialto Bridge from the South” by Giovanni Antonio Canal, known as Canaletto (1697–1768), dated ca 1720.

This is a classic vedute, a genre that flourished in Venice in the early 18th century. Such works were not souvenirs in the modern sense, but prestige objects, often commissioned or bought by wealthy foreign visitors. And obviously the Rialto was a prime theme, being the commercial heart of Venice, with its markets, banks, warehouses, money changers, etc. By 1720, the bridge (completed in 1591) was already a symbol of Venetian wealth and civic order (or lack of).

I’ve always loved Canaletto for his exceptional architectural precision, and his use of a camera obscura (inferred rather than documented). But also because he captured people, boats, buildings in such a natural but elegant way. I can spend hours looking at the detail.

Of course it reflects how Venice wanted to be seen, and how foreign buyers wanted to remember it. It’s not a candid scene, it’s an exportable and reassuring view of Venice fit for walls in London, Paris, or Vienna.

In this sense it aligns perfectly with the Louvre Abu Dhabi’s mission to show shared urban, mercantile, and visual histories.

I will admit, I visited the permanent collection taking a few photos of things that attracted my eye. Now faced with using one of them as a closing object, I’m not convinced.

I will use “Between Darkness and Light” by Marc Chagall. It was painted between 1938 and 1943, during a period when the artist lived between France and the United States, having fled Europe following the rise of Nazi persecution of Jews. We actually don’t know exactly where it was painted, or when.

The work belongs to a group of paintings produced by Chagall during the years surrounding the Second World War, when themes of displacement, conflict, and identity became prominent in his work. The composition combines a central human figure with surrounding symbolic and narrative elements drawn from personal memory, religious imagery, and contemporary events. Chagall frequently employed such composite structures rather than single-point narratives, assembling figures and scenes within a unified pictorial space.

Luckily a temporary exhibition on the Mamluks gave me the ideal “end of visit” artefact, the Baptistery of Saint Louis. One of the most famous and puzzling objects in medieval Islamic metalwork.

It’s a large brass basin (copper alloy), decorated with silver and gold inlay.

The metalworker Muhammad ibn al-Zayn, who signed the object six times, so I’m guessing he was happy with his workmanship.

It dates from ca 1320–1340 (early 14th century) and was probably made in Cairo or Damascus during the Mamluk Sultanate.

The basin is completely covered in narrative imagery. There are mounted horsemen, foot soldiers, and attendants, sultans, emirs, and courtiers, and hunting scenes with animals. There are no Christian symbols, no coats of arms, and no dedicatory inscriptions. In fact despite the courtly Mamluk imagery, there are no signs of religion.

No names, no text explains its function, and no contemporary document describing it.

Everyone agree that it was not made as a baptismal font, but may have been used for handwashing rituals.

It was only in the 15th century, the basin appears in an inventory of the royal Château de Vincennes. How it got there is unknown.

But once found, the basin was repurposed as a baptismal font. It was used to baptise royal children, most famously Louis XIII in 1606.

However, the name “Baptistery of Saint Louis” only appeared in the late 18th century. And it refers retrospectively to Louis IX (reigned 1214–1270), despite there being no historical link between Louis IX and the basin.

It was only in the late 19th century, art historians finally recognised the object as one of the finest surviving examples of Islamic inlaid metalwork.

Every detail leaves a question mark. Our horseman is armed (mace or staff), suggesting a military role, but he wears a conical hat with a brim, not a Mamluk military helmet. Yet military elites always wore recognisable helmets or turbans. He sits within a medallion, a framing device usually reserved for high-status figures, and it is not a generic face, but he is not named. The horse is richly harnessed, but not parade-perfect. This is not a courtly artefact, yet there is no sense of triumph, so why was such an elaborate and very prestigious piece made?

The Dome

Here and there, is access to a roof terrace, which provides an overview of the dome. But the most impressive views are from under the dome.

This is not a decorative dome, it is a major piece of environmental engineering. The diameter is ~180 metres and it weighs ~7,500 tonnes. It is built up of 7,850 unique star-based geometric motifs in 8 superimposed layers (4 structural steel amd 4 aluminium cladding layers). The dome is not constructed of several 1,000s of individual “star”, but a series of 85 super-structures each 5 metres thick and weighing between 30 and 70 tonnes.

The dome is supported by four massive concealed concrete-and-steel piers, integrated into the buildings below. The idea was to create a dome that floated above a village of buildings.

Sunlight passes through the layered geometry, with each layer blocking part of the solar radiation. The overlapping patterns ensure no direct, sustained solar exposure.

This mimics palm-leaf shading in traditional Gulf architecture, scaled up to monumental size. The architect wanted a Medina-like street networks and a desert tent logic. This means exploiting the local breezes, favouring gentle, continuous air movement, and evaporative cooling from the water.

Its thought that the dome reduces the local air temperature by as much as 5°C.