I’m not sure how many people know what a dune buggy is. Well, in Oct. 1974 I went out and bought one for £200.

I had been accepted for a 3-year PhD research grant in a place called Ispra in Italy, but I was having problems finding out where it was. There was no mapping software in those days, and the place was so small it did not appear in any atlases.

But the priority was to find a way to get there, and buying a car was the obvious solution. I had spent 11 days in 1973 in Rome and Capri, so my idea of Italian geography was limited (to say the least).

The question was, what type of car would be cheap to buy and own, easy to repair and maintain, and would “fit in” with my idea of “Bella Italia“? This was the world of sunshine, beaches, bikinis, and Sophia Loren, Monica Vitti and Claudia Cardinale. Even James Bond had a buggy in For Your Eyes Only (albeit in 1981).

When I found out that Ispra was on a lake called Lago Maggiore. The equation was quite simple, a lake must have a beach of some sort, and that ment sand (and bikinis), so a dune buggy was obviously the ideal car for me. I didn’t realise that I would be near the Swiss boarder, and about 50 km from the Alps.

What is a dune buggy?

The dune buggy emerged in California in the early 1960s as a light, open-air vehicle built for fun on sand dunes and beaches. It evolved from a modified Volkswagen Beetle, chosen for its rear-mounted engine, simple mechanics, and wide availability. The fibreglass body, bolted onto a shortened Beetle chassis, gave the dune buggy its distinctive rounded form and low weight, allowing it to skim over soft sand with ease. Bruce Meyers’ 1964 Meyers Manx set the pattern with a durable fibreglass shell, lifted suspension, and off-road tires, all wrapped in a look that embodied freedom and coastal ingenuity. Its success sparked an explosion of imitators and kit versions. Because the concept relied on a standard VW chassis and parts, almost anyone with a few tools and a garage could copy the basic design and build one themselves.

In the United Kingdom, the dune buggy phenomenon arrived a few years after its Californian debut. By 1967–68, imported Meyers Manx kits and car magazines had introduced British enthusiasts to the concept. However, the local scene quickly developed its own identity. The damp climate and lack of open sand dunes pushed the design away from pure beach use toward road-legal fun cars built for summer driving and local car shows rather than off-road play.

By 1969, homegrown manufacturers began producing kits adapted to British conditions and regulations. Companies (e.g. Bugle) offered variations based on the Volkswagen Beetle floorpan, often with subtle styling changes, e.g. wider wings, hardtops, or even full windscreens and weather gear. The GP Beach Buggy, introduced in 1970, became one of the most popular UK versions, known for its solid build and practical layout suited to narrower British roads.

During the early 1970s, dozens of small firms entered the market, selling DIY kits advertised in motoring magazines and at kit-car shows. Production peaked between 1971 and 1973, when owning or building a buggy was seen as an affordable way to capture the carefree Californian spirit without leaving home. British law required lights, mudguards, and other road equipment, so most buggies were registered as re-bodied Beetles rather than new vehicles.

By the mid-1970s, the boom had faded. Stricter regulations, rising costs, and changing tastes, along with the oil crisis of 1973–74, reduced demand. Many small manufacturers folded, leaving a handful of survivors like GP and Bugle still producing limited numbers. Yet the legacy endured, and by 1975, thousands of UK enthusiasts had built their own buggies from kits, proving that, just as in California, the idea remained wonderfully democratic. Anyone with a donor Beetle, a few tools, and some imagination could create one.

What about my dune buggy?

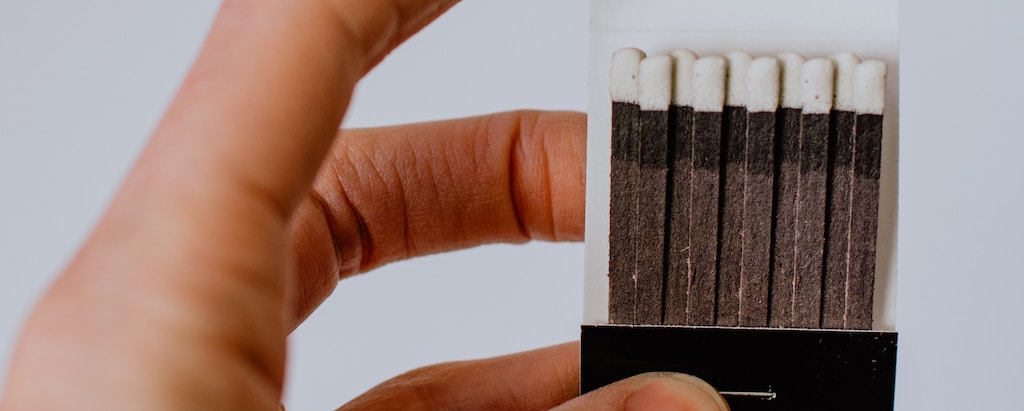

My buggy was built on a shortened 1966 Beetle chassis with a 1200 cc air-cooled engine. I know exactly how much it was shortened because I had a problem to find and modify a VW break cable. The Bruce Meyers’ original 1964–66 Manx design specified a 14¼-inch chassis cut, and the British GP kits copied this exactly. Shortening the VW floorpan didn’t alter the suspension units themselves, i.e. the front torsion beam and rear torsion bar assemblies were retained intact. However, the lighter fibreglass body and shorter wheelbase meant that some builders replaced the original rear torsion bars with thinner ones to soften the ride, and occasionally fitted a shorter gearbox nosecone to improve shift linkage alignment under the compact body shell. These modifications gave the buggy (as seen in the feature photo) a slightly higher rear stance once re-bodied.

The body was a fibreglass monocoque with add-on black wheel arches, exposed engine, fixed windscreen, no chrome, and no bumpers. The raised front ridge, the round headlamp pods, and the add-on black arches, were also features typical of a GP Mk I or early Mk II body shell (built c. 1969–71 by GP Vehicles in Berkshire). The simple red paint job (no metal-flake and chrome) was typical for an early budget kit. By 1971, GP Vehicles had sold hundreds of Mk I kits, most through small garages that customised details.

The wheel rims were hand-made, with widened steel rims, and extra support brackets in place. Early UK builders commonly cut the outer rim section from one Beetle wheel and welded it to another, producing a wider channel for bigger tyres. There were “support brackets” welded between the centre disc and outer rim to counter flexing and cracking. This was a home-engineered safety fix seen on early GP and DIY builds. Through 1970–72, specialist wheels were expensive and mostly imported. So many British buggy builders, especially using GP or similar kits, fabricated their own widened steels, until commercial wheels became more common around 1973. The back tyres were much wider than at the front, and they were generic road radials.

When I had finally to replace the tyres, each one (retreads) cost more than the original cost of the buggy.

The roof and frame consisted of a single thick roll-bar (painted, not chromed) with clip-on vinyl roof and roll-up side curtains with windows. This was a GP soft-top option available from around 1970, using a central hoop that doubled as roll protection. It fixed to the windscreen frame and rear deck lip with snap fasteners.

Inside there were two decent-quality fixed vinyl front seats on simple tubular frames that pivoted forward for rear access. There was a loose rear bench seat not bolted down. The dashboard was a simple flat panel with minimum instruments (standard GP Mk I).

So the exterior had no bumpers, no chrome, large fuel filler on the bonnet, flat rear lights, and a simple candy-red gelcoat finish. The large front petrol tap/filler was a hallmark of GP shells, which used a top-mounted cap feeding the original Beetle tank underneath the bonnet hump.

The mechanics used a stock carburettor and single silencer, but being light weight (~550 kg) it performed surprisingly well with just 34 bhp. Steering and braking remained stock Beetle (worm-and-roller, drums all round).

So my buggy was built between 1970 and early 1972, almost certainly from a GP Mk I kit purchased before the company’s Mk II redesign. It was probably assembled by a small garage or an experienced amateur, then sold on and re-registered before I bought it in late 1974.

Completed roadworthy buggies, built from kits and registered, appeared in Exchange & Mart classifieds for between £250 and £450 in 1973–74. Homebuilt examples with no chrome, standard engines, and plain gelcoat commonly traded £180–£250.

So my £200 was about right for Oct. 1974.

Life of a buggy in Italy

The most important thing was that my future wife, Monique, fell in love with it. The hood would not stay on at speed (like >10 km/hr), so it was only used when parked (and then rarely). We went everywhere with the buggy, skiing in a open top in winter (naturally it had no heating), carrying 7-8 people down to the beach at the local lake (the back could “seat” 6 or 7 if they all held on to the roll bar), and my 1974 tax disk remained in perfect condition through to when we sold the buggy in Nov. 1981. The buggy went to a good local Italian family who loved it as much as us (for a nominal Lira 100.000 or about £50).

We would park it anywhere, and no one said anything. It always attracted a smile and wave, and the local Carabinieri loved to stop us just for a chat. We never paid a fine, but in the late-70s they did insist that we get new tyres.