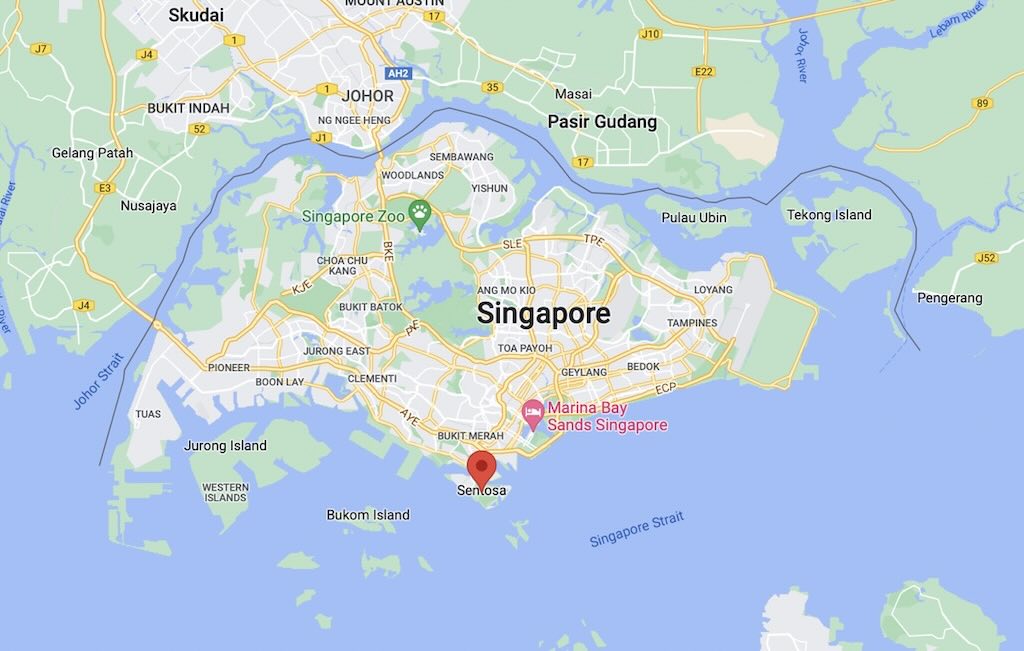

This is a report on a New Scientist tour, hosted by Kirker, entitled CERN & Mont Blanc: Dark and Frozen Matter.

In very simple terms the trip consisted of:

Tuesday 7 Oct. 2025 (Day 1) – Arrive in Geneva

Wednesday 8 Oct. 2025 (Day 2) – Visit Geneva

Thursday 9 Oct. 2025 (Day 3) – Visit CERN

Friday 10 Oct. 2025 (Day 4) – Visit Chamonix

Saturday 11 Oct. 2025 (Day 5) – Visit Geneva

Sunday 12 Oct. 2025 (Day 6) – Leave

I had visited Geneva and the Mont Blanc, so my real interest was in the presentation and visit to CERN.

I had pre-booked this trip some months ago, and I was quite surprised to see that I would have 13 fellow travellers, 5 from the US, 6 from the UK, 1 from Ireland, and 1 from France. I didn’t suspect that CERN would be such a tourist attraction, or Geneva-Chamonix for that matter. However, I was told that the visit to CERN was very popular, and groups are often larger.

Tuesday 7 Oct. 2025 (Day 1) - Arrive in Geneva

The drive down to Geneva was uneventful.

I have a separate report on the Hotel Royal Manotel.

Everyone met at 19:20 and walked to the Casa Rostra restaurant for dinner. The restaurant was almost next door to the hotel. The atmosphere was fine, but a bit “over the top Italian” (but not unusual in a tourist city).

They initially served some bruschetta, which was a joke. Ideally it should be a slice of rustic bread (pane casareccio / pane toscano) grilled over a wood fire, rubbed with garlic, and drizzled with the fresh olive oil. Tomatoes and basil came later, likely after the 16th century, and are used more in Rome than Tuscany.

Outside Italy, restaurants often replace rustic bread with the baguette. The importance is that the bread is well toasted, the raw garlic cloves and tomatoes should be fresh, and the olive oil “full bodied”. The slice should be thick enough to char lightly outside and hold the olive oil and tomato without collapsing.

What we got look to be small, very lightly browned, “pulled apart” pieces of focaccia, with what was probably some kind of whitish garlic sauce from a bottle, and some diced fresh tomato.

The starter was a plate of rucola (rocket), with a few slices of tomatoes topped with mozzarella di bufala. It was edible.

The main was penne al arrabbiata. The pasta was cooked al dente. I’m not sure but it looked like the tomato sauce was added to the pasta (which I don’t think had been sufficiently well drained). The traditional way is to toss the penne directly into the pan with the home-made sauce, and mix over medium heat for 1–2 minutes. This way the pasta is glossy and nicely coated. The “arrabbiata” was served separately as a very spicy olive oil sauce (looked home-made), with the recommendation to be very, very careful. So most people did not take the sauce (which was very intense), and so did not actually eat penne al arrabbiata, but just penne al pomodoro. For some Romans it’s “no cheese”, but for the others it should have been Pecorino Romano. Again it was edible (I was hungry).

Dessert was “tiramisu du chef“, with biscuit, full cream, mascarpone, sugar, cacao, and coffee. This appeared to be a very average Frenchified version, richer but less airy. They didn’t use Savoiardi (ladyfinger biscuits), and certainly didn’t use enough biscuits (which should represent at least 50% of the dessert). They didn’t make a mascarpone cream made from egg yolks, sugar, mascarpone, and then whipped with egg whites. They probably just used only crème entière instead of the classic egg-based zabaglione-style. And it didn’t taste like unsweetened espresso. So the dessert was heavy and a bit soggy, e.g. it collapsed on the plate.

So an inauspicious start to the week.

Wednesday 8 Oct. 2025 (Day 2) - Visit Geneva

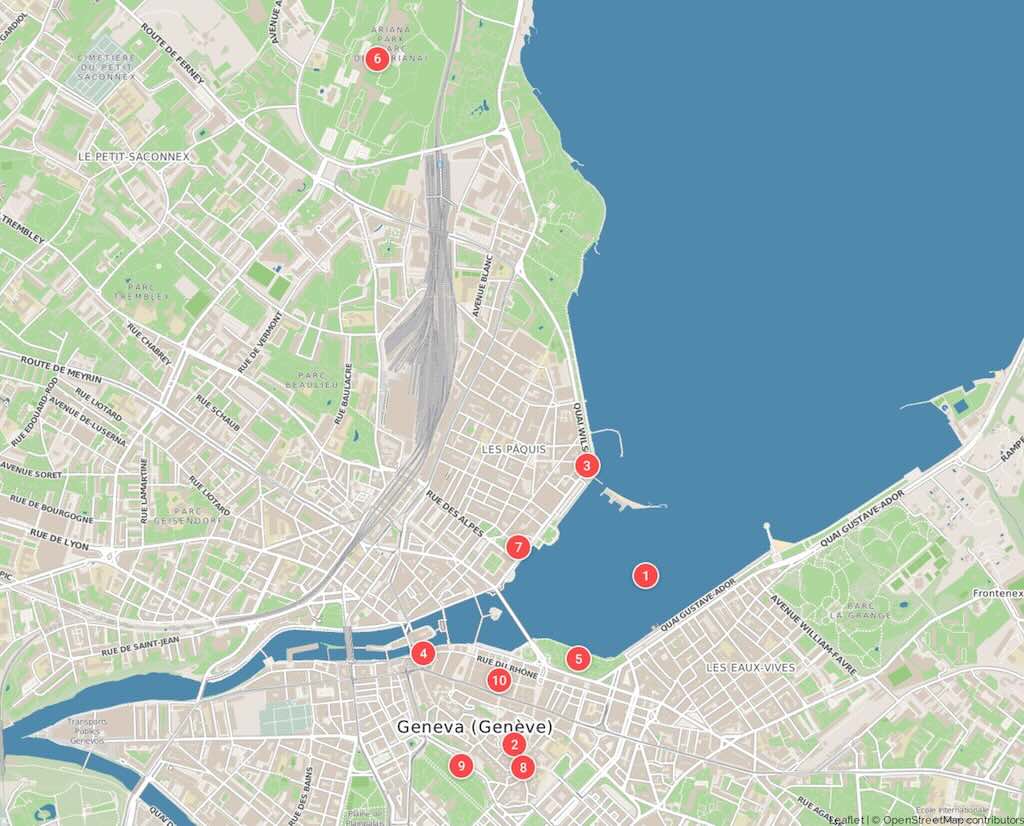

The morning was dedicated to a walking tour of the Old Town, with a professional guide from the local tourism office. The day started with a stroll down to the Brunswick Monument (N°7), a neo-Gothic mausoleum built in 1879 to honour Charles II, Duke of Brunswick, who left his fortune to the city. Unusually his sarcophagus lies prominently above ground within the ornate canopy, not beneath it. What is far less known, is that during the monument’s construction, Geneva’s city archives record that the sculptors secretly inserted a small bronze token engraved with the city’s motto, “Post tenebras lux” (After darkness, light), into the base of one column. It has never been removed or publicly acknowledged.

A little-known facet of the Duke lifestyle is that he lived much of his later life under assumed names in Paris and London, obsessively disguising himself to observe how people spoke of him.

According to correspondence in private collections (not in the Geneva archives but in Hanover), he kept a ledger where he rated his own notoriety. He gave himself scores for “dread”, “envy”, and “admiration”. One entry, dated 1870, reads, “Geneva will not forget — for I shall make her remember”.

That private ledger vanished after his death and has never resurfaced, and its existence is known only through a brief mention in a solicitor’s letter found among his estate papers.

We then walked along the Quai du Mont-Blanc to the Genève-Pâquis (usually just called Pâquis), on the Rotonde du Mont-Blanc.

There we took a small yellow water taxi called “Mouettes Genevoises” (Geneva Seagulls) across La Rade to Quai Gustave Ador (and the Old Town).

The taxis have been operating since 1897, shuttling passengers across Lake Geneva (Lac Léman) and linking the left and right banks via four main lines, each marked M1 to M4 (ours was M2). They are officially part of the TPG (Transports Publics Genevois) system. We had received from the hotel a nominative transport pass for the Canton of Geneva, which included these water taxis.

In theory they can ask to see the transport pass and an ID, but no one asked us during our 5-day stay.

It’s a bit weird that “rade” in French is actually roadstead in English. From the 14th century, the word combines “road” (from Old English rād, meaning “journey” or “riding place”) and “stead” (meaning “place”). So it literally means “a place for riding [at anchor]”.

We will stop for a moment to look at why the lake is called Lake Geneva in English and Lac Léman in French. Originally the name Léman comes from the ancient Latin “Lacus Lemanus”, (possibly Celtic meaning “large body of water”). During the Middle Ages it was often called Lac de Genève, then Lac Léman resurfaced in the Renaissance. In French, the official and locally preferred name is Lac Léman. In English, tradition and geography favour Lake Geneva, emphasising the city that dominates its western end.

Each Mouette carries about 20–30 passengers and crosses the lake every few minutes.

Beneath the varnished wood benches of the oldest Mouettes, there should be brass plaques naming their original patrons, the Geneva families who financed individual boats at the turn of the century as acts of civic pride. I did check but our taxi was one of the modern ones.

Our walk around the Old Town took us past the Molard Tower (N°10 La Tour du Molard), on top of the Reformer’s Wall (N°9 Mur des Réformateurs), through Place du Bourg-de-Four (N°8), and into St Peter Cathedral (N°2 Cathédrale Saint-Pierre). We also walked “briskly” along Rue d’Enfer and Rue du Purgatoire.

We can see the Molard Tower above (ca. 1870), when the place was still closed côté lac. The tower is still attached to its left, but the building to its right has been demolished creating an opening to the lake.

During a restoration of the Molard Tower in 1903, they found a small wooden tablet sealed behind one of the coats of arms. It bore a hand-drawn plan of the Molard as it stood before the Reformation. There was a chapel dedicated to Saint Nicholas attached to its inner side, but it had been erased from records after 1535. The drawing was quietly filed in the Archives d’État under “divers plans anonymes”. Our guide mentioned this.

Some people might think that Rue d’Enfer and Rue du Purgatoire might be linked to a religious moral, but no, they are linked to taxation. City rolls from 1458 show that “Enfer” marked the lowest, most flood-prone lane (where rents were damnably low), and “Purgatoire” was the narrow uphill passage where owners had to pay a cleansing fee for drainage into the main gutter. The names were literal fiscal jokes before they became moral metaphors.

The last stop before lunch was the cathedral, which is located at the highest point of the Old Town (the website is worth a visit). It was originally built between the 12th and 13th centuries as a Romanesque and later Gothic cathedral. It became the centre of the Reformation in the 16th century when John Calvin preached there, leading to the removal of most Catholic ornamentation and the adoption of a stark, austere interior that was a deliberate reflection of Protestant ideals of simplicity and focus on scripture.

We can see quite a mix of styles, namely:-

- Front portico (left) – an 18th-century neoclassical addition with Corinthian columns and pediment, giving the medieval church a restrained classical façade.

- Central dome (behind portico) – part of the same neoclassical renovation, built over the crossing.

- Gothic body – the main medieval church built between the 12th and 15th centuries is only visible as a small corner between the portico and the chapel.

- Green spire (rear) – a copper spire added in the 15th century, crowning the crossing tower.

- Whitish bell tower (far right) – the original Romanesque tower, built of lighter stone, one of the oldest surviving parts.

- Chapel of the Maccabees (right foreground) – the projecting Gothic chapel with large traceried window, richly decorated inside, dating from the late 14th century.

Despite the overall restraint, one part escaped this severity, namely the Chapel of the Maccabees, built in the late 14th century. It was lavishly restored in the 19th century and today stands out for its richly coloured Gothic decoration, gilded details, and intricate vault paintings. It makes for a very striking contrast to the otherwise bare cathedral interior.

The Chapel of the Maccabees was built in 1397 by Cardinal Jean-Allarmet de Brogny as a funerary chapel. It was dedicated to the Seven Maccabee brothers, Jewish martyrs described in the Second Book of Maccabees, who were tortured and killed for refusing to abandon their faith. In Christian tradition they symbolised steadfastness and faith under persecution, so a theme appropriate to a burial chapel and to the moral tone of late medieval devotion.

Originally, like many Gothic chapels, it was richly painted and gilded to evoke the splendour of heaven. In fact colour was a form of theology, and each colour symbolised a different facet of the truth, namely:-

- Light as divine presence, was represented by stained glass and painted vaults which transformed sunlight into coloured radiance, and was a metaphor for the way divine grace transformed the material world.

- Gold represented divine light and heavenly glory. It didn’t just shine, it was the colour of eternity.

- Blue (especially ultramarine, made from lapis lazuli) symbolised the Virgin Mary, faith, and the infinite sky of heaven.

- Red evoked sacrifice and divine love, often associated with Christ’s passion.

- Green meant renewal and hope, with the promise of eternal life.

After the Reformation in 1535, the chapel was stripped and used for secular storage. In the 19th century, architect Jean-Baptiste Lassus restored it in neo-Gothic style (1850s), carefully recreating the brilliant polychromy (red, blue, gold, and green) that medieval interiors once had. The goal was both historical accuracy and symbolic revival, showing what the medieval church might have looked like before the Reformation’s austerity.

The word “maccabee” is sometime used as slang for a dead body, but a Maccabee is, in origin, a member or follower of a Jewish rebel family who fought against Greek (Seleucid) rule in the 2nd century BC. In later Christian thought, the name came to stand for unwavering faith under persecution, which is why the Seven Maccabee brothers became symbols of steadfast belief and were venerated as saints.

We stopped for lunch au Grütli for a very well prepared 3-course lunch menu. I passed on the starter, and took the orecchiette, pumpkin spice, arugula (just rocket again), Grana Padano, toasted seeds, and cherry tomatoes. It was excellent, despite it being fusilli and not orecchiette. I then took the lemon pie, which was really good and had a pleasant tang.

Highly recommend. It was the best meal of the trip.

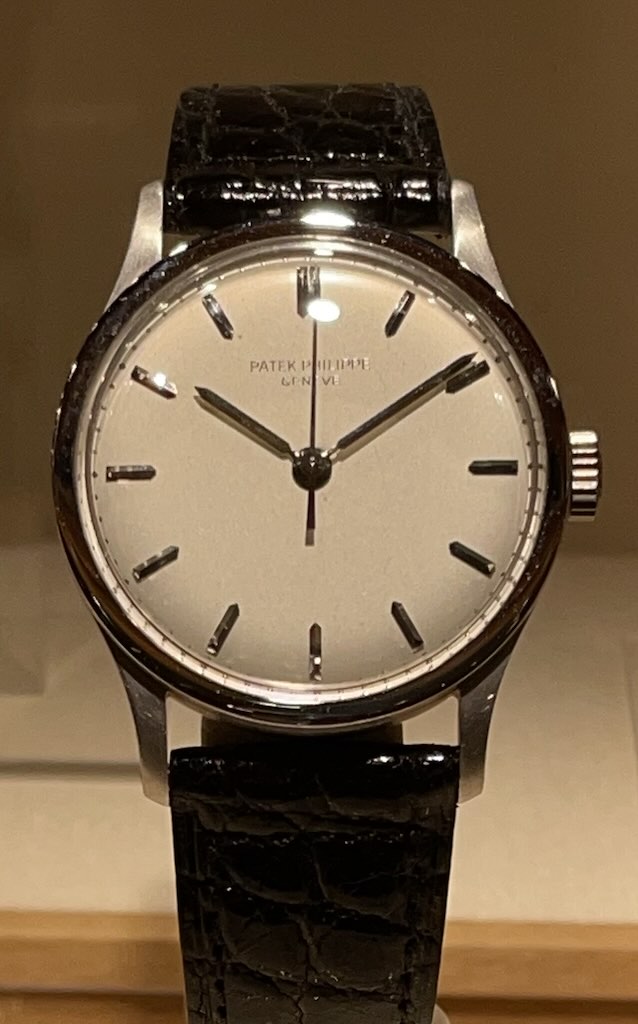

Our afternoon was dedicated to a guided visit to the Paket Philippe Museum. We had one of the museum’s private guides, and we spent a good two hours visiting first the collection of antique time pieces (2nd floor), and then the Patek Philippe Collection on the 1st floor.

The craft of clockmaking had roots in Europe by the Late Middle Ages. Mechanical timekeeping originated not in Switzerland but in the urban and monastic centres of late-medieval Europe, roughly between 1270 and 1350. The earliest true clocks were tower clocks using verge-and-foliot escapements, driven by weights, and regulated not by springs but by crude balances. The Salisbury Cathedral clock (ca. 1386) is one of the oldest surviving examples.

Around 1450–1500, European artisans began to miniaturise mechanisms using spring-driven power instead of weights. This enabling the first table clocks and “Nuremberg eggs” (portable watches). The German regions of Nuremberg (see Peter Henlein) and Augsburg were key, but this period also saw the rise of ornamental clockmaking, e.g. gilt-brass cases, engraved dials, astronomical indicators, which blended metallurgy, engraving, and emerging precision mechanics. Geneva’s goldsmiths and engravers absorbed these northern and Italian influences during the early 16th century, precisely as Calvinist restrictions on jewellery redirected craftsmanship toward precision mechanics (clocks, watches) rather than ornamentation. In 1601 the Watchmakers’ Guild of Geneva was founded as a formal institution that helped regulate craftsmanship, quality, and training.

Over time, watchmaking expanded from Geneva outward into the Jura foothills, which offered cooler climates (better for metal work), isolation (cheaper land and lower costs), and a tradition of artisan workshops. The Swiss adopted a system of “établissage”, whereby specialised small firms (établisseurs) would make individual components (cases, dials, hands, movements) and assemble them, creating a flexible networked manufacturing structure. Daniel Jeanrichard is often credited with pioneering aspects of this in the late 17th–early 18th century.

It is useful to understand how a timepiece is made. Firstly, a manufacture d’horlogerie produces the essential components of a movement, notably the ébauche, the unfinished set of plates, bridges, and gear train parts that form the mechanical core. These ébauches, along with balance assemblies and escapements, are delivered to an établisseur, a factory that practices établissage, the system of assembling watches from many independently made parts. Within this process, a chablon refers to a movement that is partly assembled but lacks the dial and hands. From this stage, the work continues through terminage, in which the termineur (independent assembler or workshop) performs the detailed fitting, adjustment, and finishing. Once assembled, the movement is “sprung and timed” (regulation and accuracy testing), then fitted with its dial, hands, and case. A remontoire, if used, provides a secondary power source ensuring steady energy delivery from the mainspring. Finally, the completed watch undergoes final inspection before dispatch. It’s important to distinguish between a company which makes its own ébauches, from an atelier de terminage, which merely assembles and regulates purchased ones.

As pocket watches became more common in the 18th and 19th centuries, Swiss makers progressively improved precision (temperature compensation, jeweled bearings, chronometer standards). By 1790, Geneva was already exporting over 60,000 watches per year.

After World War II, Swiss watch exports boomed, however, from roughly 1970 to 1985, the Swiss watch industry went through a serious depression (the “quartz crisis”). Electronic and quartz technologies (mainly from Asia) undercut mechanical watchmakers. Many firms failed or consolidated, and the surviving firms leaned into branding (“Swiss Made”), mechanical excellence, luxury positioning, and innovations to differentiate themselves. For example, In 1985, Audemars Piguet produced the world’s thinnest self-winding perpetual calendar, Vacheron Constantin produced ultra-flat repeaters, calendars, and chronographs, Audemars Piguet released the ultra-thin wristwatch tourbillon, and Patek Philippe assembled 33 complications (e.g. perpetual calendar, moon phases, sidereal time, thermometer, etc.) into a single watch.

Patek Philippe traces its roots to 1839, when Antoine Norbert de Patek (a Polish expatriate) and Franciszek Czapek founded Patek, Czapek & Co in Geneva. In 1844, at an industrial exhibition in Paris, Patek encountered Jean Adrien Philippe, who had developed a mechanism for keyless winding (stem winding). Shortly afterward, Philippe joined, and the company reorganised as Patek, Philippe & Cie. Since 1932, the Stern family has owned Patek Philippe (Stern were originally dial manufactures). It is often cited as one of the few remaining large Swiss watch manufactures still privately and independently owned, and it maintains extensive in-house capabilities (movement design, case making, finishing, complications) rather than outsourcing major elements.

Patek Philippe has filed over 100 patents in its history, reflecting continuous research in chronometry, complications (e.g. perpetual calendars, minute repeaters, split-seconds chronographs). The company remains entirely private, with no outside shareholders or public listing, which is unusual among major luxury brands. The company also keeps detailed archives, so owners can request an “Extract from the Archives” which draws from records dating back to 1839, verifying a watch’s original features, date of sale, etc.

The Patek Philippe Museum is a serious institution preserving horological heritage. The museum officially opened in November 2001, and is essentially a privately funded institution, originating from the personal collecting efforts of Philippe Stern (former head of the company).

The museum holds about 2,500 pieces, watches, clocks, automata, enamel miniatures, and enriching objects spanning five centuries (16th century to present). It also maintains a specialised library of over 8,000 works on horology. The museum is organised broadly into two main thematic divisions “historic timepieces” on the second floor, and the Patek Philippe collection on the first floor.

The museum is amazingly popular with more than 600,000 visitors, it has become one of Geneva’s cultural landmarks.

I managed to take a few photos, so I’m going to try to just use them to give a flavour of our visit.

This is a late-Renaissance “Jour et Nuit” pendant watch with sundial (Germany, 1570). It’s an early hybrid between a mechanical timekeeper and a portable scientific instrument. The lower section is a small spring-driven watch with an engraved gilt-brass dial, while the lid contains a horizontal sundial with a hinged gnomon and a small compass to orient it toward north. The outer ring of Roman numerals marks the twelve hours, while the inner 24-hour scale divides day and night (“jour et nuit”).

The whole object is compact enough to be worn as a pendant, one of the earliest known forms of personal, portable timekeeping. It’s richly ornamented, suggesting it was made for a noble or scholarly patron.

The combination of mechanical and solar time in one object reflects a transitional moment in horology. In the mid-16th century, mechanical clocks were still being checked and corrected against sundials, so this watch embodies that interdependence. The sundial maker Markus Purman and the possible movement maker Hans Koch both worked in German centres known for mathematical and astronomical instruments (Augsburg or Nuremberg). These cities were then Europe’s leading workshops for portable dials, astrolabes, and early watches. By 1570, mainspring and fusee technology had just begun to allow watches to run for several hours between windings. Accuracy was poor by later standards, but the achievement was miniaturisation, i.e. fitting gears, verge escapement, and balance inside a palm-sized case.

This mid-17th-century (ca. 1645) pendant watch combining early French mechanical watchmaking with the finest painted enamel decoration of its time. The outer and inner covers depict episodes from the Life of the Virgin Mary, rendered in polychrome enamel on a white ground. The inner cover shows the Visitation while the dial itself bears the Virgin in prayer, surrounded by Roman hour numerals and a single gilt hand.

The enamel technique, probably painted on gold, achieves exceptional detail and colour depth, rivalling miniature portrait painting. The casing was intended to be both devotional and ornamental, a portable expression of piety and status.

The maker, François Baronneau, is known to have been active in Paris in the early 17th century. He was part of the first generation of French watchmakers after the craft had spread from Germany and Geneva into France. By the 1640s, Parisian workshops were noted for combining technical refinement (spring-driven watches, improved escapements) with luxury craftsmanship (enamel painting, repoussé goldwork). The watch’s devotional theme reflects the Counter-Reformation era’s emphasis on visible faith, especially in Catholic France under Louis XIII and Louis XIV.

The object demonstrates how early watch cases became miniature canvases for religious or mythological scenes. Enamelled dials like this required repeated firings at precise temperatures, where each misfire could destroy weeks of work. Portable sacred imagery allowed the wearer to carry both time and prayer, an emblem of moral and temporal order.

Around this date, watches began moving from being curiosities of the wealthy toward symbols of personal identity and virtue.

This fantastical object is part of a matched pair of jewelled pistols, each containing both a scent-sprayer mechanism and a small watch concealed in the handle (ca. 1805). The barrel and grip are richly enameled in translucent red and deep blue over engine-turned guilloché gold, bordered with seed pearls and chased gold mounts. Pulling the tiny trigger releases not a bullet but a puff of perfume through the nozzle at the front. A theatrical flourish of courtly flirtation rather than violence.

In the butt of the grip, beneath a hinged cover, is a small circular watch dial with Roman numerals, allowing time to be read discreetly.

Mouliné, Bautte & Cie was the partnership of Jean-François Bautte (1772–1837), one of Geneva’s great entrepreneurs, later associated with the firm that became Girard-Perregaux. Bautte’s workshops were famous for turning everyday or fanciful objects (e.g. fans, snuffboxes, miniature pistols) into mechanical jewels incorporating watches, music, or perfume. Around 1800–1810, Geneva exported such pieces to Ottoman, Persian, Russian, and Chinese courts, where they were prized as marvels of European ingenuity.

Combining horology, automaton engineering, and perfumery in a single miniature device was a technical tour de force of early micro-mechanics. Genevan enamel mastery, and in particular the use of translucent enamel over guilloché metal was a hallmark of Geneva’s decorative arts circa 1800, and it demanded precision firing and perfect polishing.

This represents Geneva’s golden age of mechanical art, when the city’s workshops rivalled Paris in elegance and invention.

This singing bird cage represents the pinnacle of Swiss automaton art in the early 19th century. Standing on ornate gilt feet, the piece features a gilded and enamelled structure in the form of an openwork dome, richly decorated with filigree goldwork, translucent blue and black enamel, pearls, and miniature architectural columns.

Inside the cage, two mechanically animated birds perch on a golden branch. When activated, they turn their heads, flap their wings, open their beaks, and sing in a coordinated natural rhythm. Beneath the cage, in the octagonal base, a small watch dial is set into a patterned guilloché panel. We see timekeeping and musical automata united in a single luxury object.

The title given to this piece Sérénade orientale reflects the fascination with the “East” in early 19th-century Europe. In addition singing birds embodied harmony, nature’s voice, and the triumph of mechanical ingenuity over silence. Their motion was both entertaining and also demonstrated human mastery of life-like automata. The combination of watch, clock, and bird automaton was typical of Geneva’s export trade to the Ottoman Empire, Persia, China, and India, where such objects were prized as marvels of Western artistry.

The maker is not known, but pieces of this sophistication are closely associated with Jacquet-Droz, Les Frères Rochat, and Blaise Bontems, which were Geneva and Neuchâtel ateliers famous for singing-bird mechanisms.

Around 1800–1820, Geneva’s artisans perfected a system in which a miniature bellows and whistle system imitated bird song, driven by the same spring barrel that powered the movement. The lifelike movement of the birds was achieved by cams and levers controlling multiple axes of motion, a triumph of pre-industrial micro-mechanics.

By 1815, Switzerland had turned mechanical art into a global export industry. Objects like this, delicate, musical, and alive with motion, helped define the reputation that would later evolve into Swiss watchmaking supremacy.

Just a final pointer to the watch that I preferred from the Petek Philippe collection. It is the Calatrava, from 1965. For me, the design philosophy of purity and restrained elegance making it a timeless example. It’s slim, uncluttered, and could have been produced almost anytime in the 20th century. It was first introduced in 1932 where the Bauhaus principle of “form follows function” was being applied to horology.

The evening meal was in Le Bistro of the hotel. I didn’t take the starter, and the main course was chicken supreme with some small roasted potatoes and a few mushrooms. Overall the plate was quite tasty, but let down by the chicken. This particular bird obviously had had a long and very active life, and surely put up a fight until the end. In other words, a tough, old bird.

Dessert was I think something in chocolate. I can’t remember it, which is probably to its advantage.

So a meal that was poor-to-near-average, but hovered over disappointing.

Thursday 9 Oct. 2025 (Day 3) - Visit CERN

Separate report in preparation.

Friday 10 Oct. 2025 (Day 4) - Visit Chamonix

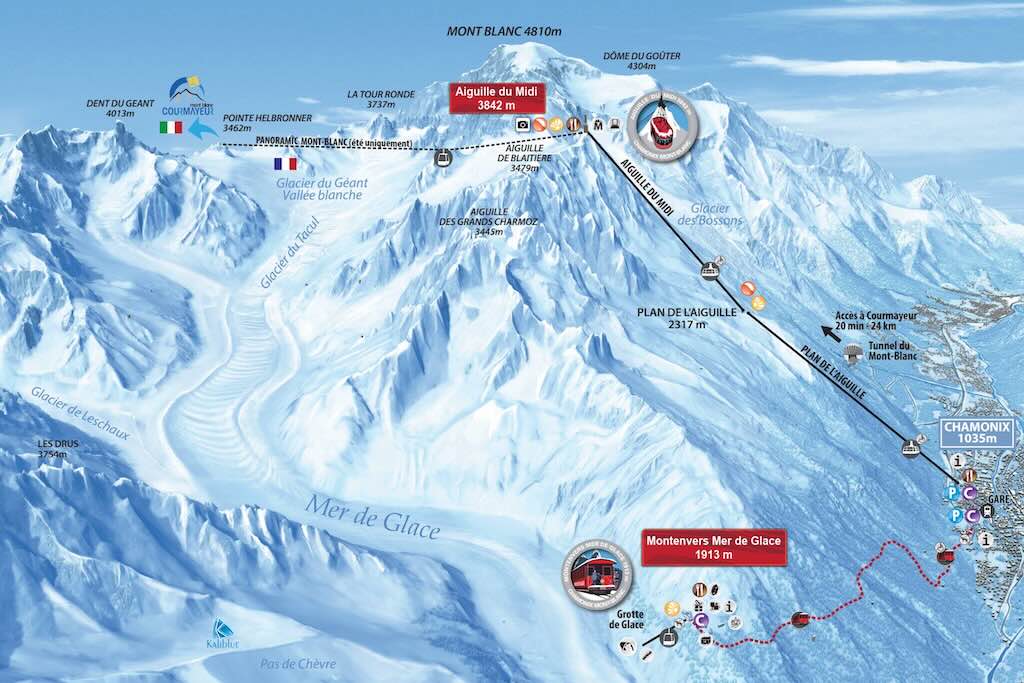

Today was dedicated to visiting Chamonix and la Mer de Glace. In the morning we visited the foot (ablation zone) of the glacier seen from the Gare du Montenvers, and in the afternoon we saw the head (accumulation zone) of the glacier from the Aiguille du Midi.

We drove in a small minibus to Chamonix, met our guide, and started the first part of the day with a trip on the Chemin de fer du Montenvers. This is a 5.1 km rack railway line that runs from Chamonix, to the Hotel de Montenvers station, at La Mer de Glace, at an altitude of 1,913 metres.

The story goes that initially the people of Chamonix did not see a train as “progress”. They opposed it, fearing that sordid “foreign” manipulators (anyone non-Savoyards) would come and steal their main business, which was the occasional hiking trip in the mountains. They were already many hundreds of professional guides competing for a small number of rich clients. They feared that the railway would take their “daily bread”. But this was not the case, because with the railway there was a substantial increase in the number of tourists attracted to the mountain. So many tourists, that the guides would also take the train to access more rapidly the high peaks.

Initially it was with steam locomotives, but in 1953 the line was electrified, using an overhead line at 11 kV AC and 50 Hz. Trains run at 14 to 20 km/h and take 20 minutes for the journey.

Check out Le Montenvers – Monsieur Perrichon en pantoufles sur la Mer de Glace. for an in depth explanation of the early days of the railway.

There were 8 steam engines, and curiously they had two false axles driven by an unorthodox set of connecting rods, and two cogwheels (barely visible) meshing with a rack. These were the real driving wheels because this train was being driven on a toothed rail (the rack) fixed between the running rails, which engaged with a cogwheel (the pinion) on the locomotive. At the ends, there were two apparently load-bearing axles, but the first could also be the motor for movements in the station where the track was level.

One of the main reasons why the steam trains were changed to electric trains was simply because every trip needed between 350 and 400 kg of coal, which was far from readily available locally. Once the decision made, all 8 stream engines were sold, including N°8 in 1979 and N°7 in 1981. Later, the two were found parked in a warehouse, forgotten by the buyer. So they were brought back to Chamonix in 2009.

Another special feature, not easily visible on the photo, was that the boiler was inclined (chaudière inclinée). In English this was called “kneeling cow” and in French “vache à genous“, or “une vache agenouillée sur ses pattes avant”. The idea is the boiler looks as if it is leaning forward, or has it nose down. It’s mentioned that they are (for example) “set at” 9°, or it mentioned that they are inclined at 5%, to the horizontal.

The reasoning is simple, it’s to ensure that the water level in the boiler covers the firebox and internal tubes, when the engine is on an incline. This prevents priming and avoids exposing hot surfaces, thus improving steam generation during climbing. Inclined boilers are found on a number of mountain trains, and vary between about 6° and 9°.

So the engines ran “chimney first” uphill, pushing the coaches. The idea was that the boilers fixed angle matched the normal working attitude. On decent, they coasted most of the way using rack brakes, not by reversing the boiler geometry.

Views from Montenvers station toward the Mer de Glace, still the largest glacier in France by area and ice volume. Accelerated melting from rising temperatures and debris-darkened ice has exposed unstable rock walls, turning the former “sea of ice” into a stark valley of erosion.

We are looking down at la Mer de Glace, one of the most studied glaciers in the Alps. We can only see a part of it here but today it’s about 7 km, though it once extended over 12 km in the mid-19th century. The area today (2024) is about 30 square kilometres, compared to roughly 40 square kilometres a century ago. It’s thickness was over 200 metres near Montenvers, now its less than 100 metres in most places. That loss translates to a century-scale estimate of about 1 to 1.5 Gigatonnes of water lost (or ≈ 400,000 Olympic swimming pools).

It is fed by two major tributaries, the Glacier de Leschaux and the Glacier du Tacul, and it descends northward before curving west above Chamonix.

The name was given in the 18th century for its vast, crevassed surface resembling frozen waves. And from the above postcard we can see why. The glacier ran past the hotel, and stood well about the first floor. Today to walk to the glacier, your 90 minute hike starts after taking 500 steps down to the valley floor.

La Mer de Glace is among the first glaciers systematically studied in the world. From the 18th century onwards, scientists such as Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, Louis Agassiz, and later Joseph Vallot used it to pioneer glaciology, (e.g. measuring flow, temperature, and annual retreat). The glacier has become a benchmark for Alpine climate change, with continuous measurements of ice flow, thickness, and surface elevation forming part of the GLACIOCLIM network, tracking French Alpine glaciers’ response to rising temperatures.

By 2050, models predict that La Mer de Glace could lose up to 70% of its 2020 volume, with only remnants surviving near the Tacul and Leschaux sources.

It’s time to have a closer look at where were are. Above is the Chamonix valley, and we can see the train we took in the morning, and the cable cars from Chamonix to the Aiguille du Midi. Naturally, it looks a bit different in winter.

So after a short stroll and lunch in Chamonix, we were booked on the Aiguille du Midi cable car (téléphérique de l’Aiguille du Midi). It consists of two independent aerial tramways (deux tronçons indépendants), both of the va-et-vient type (two large cabins shuttling back and forth on fixed cables).

The first section (premier tronçon) is from Chamonix (1,035 m) to the Plan de l’Aiguille station (2,317 m). Then you have to change to a second section (deuxième tronçon) from Plan de l’Aiguille to the upper station (Piton Nord, 3,778 m). From there, a lift goes up the final 42 metres to the summit terrace at 3,842 m.

The first section has three pylons (pylônes), and the second section is world-famous because it has no intermediate supports at all. It is a single unsupported span of about 2,867 m, with a vertical rise of 1,461 m. This was a world record for an aerial tramway when it opened in 1955, and remains one of the longest unsupported cable spans ever built.

Between the two sections you walk through the interior of the Plan de l’Aiguille station, a solid stone-and-concrete building acting as the anchor point for the two cable systems. Both the counterweight and motor assemblies for the first section are located here, and the second section’s cables start here and stretch unsupported all the way to the upper station. Each section has its own drive, counterweights, and cables, and the cabins from each section do not share cables or grips.

The second cable car arrives inside the Piton Nord building, which is partly carved into the granite. Here there is the drive machinery and counterweights for the upper section, a control room, and an emergency staircase down into the rock.

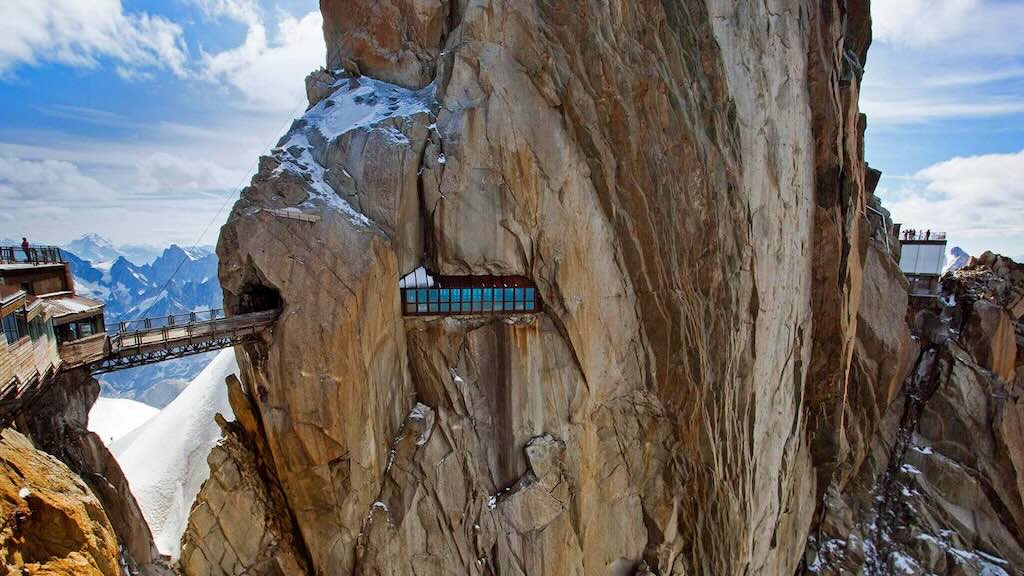

Above we have the Piton Nord on the left, then the footbridge (passerelle) to the Piton Central seen below (also called “sommet sud” on some plans). This houses the lift up to the terrasse sommitale at 3842 metres at the base of the antenna. There is a circular gallery Le Tube which wraps around the Piton Central. To the right there is the Piton Sud, which is reached by the sequence of terraces and gangways.

Below we have plan of the different terraces, walkways, etc.

You can get some spectacular photos, but often it’s difficult to appreciate the scale of the mountains around you. For example, in the above photo, the lines drawn in the snow are tracks of those going to climb the various peaks, including Mont Blanc. And in the below photo, check out the metal stairs on the bottom of the rock in the foreground.

We will close this little visit with two comments. Firstly, summer is very pleasant, but winter is an entirely different story.

Secondly, you can practice a multitude of sports from the top. There are classic climbs routes (from arête des cosmiques, the most famous mixed rock–snow ridge, or pure granite routes, narrow snow ridges, glacier ascents, ice climbing, etc.). Then there is ski mountaineering and off-piste, e.g. Vallée Blanche, ski de randonnée (ski touring), and heli-ski from the Italian side. There is paragliding, BASE jumping, and speedflying. Not forgetting glacier hiking and high-altitude trekking, or the training courses in crevasse rescue, glacier navigation, and crampon technique (by guides). And finally there are photographic / scientific expeditions (climate monitoring, geology, cosmic-ray research station, etc.).

This means that of the 2,000 to 3,000 tourists accents (peak 5,000) per day, about 350 to 500 will be doing “something” (can reach 700 or more). For the Vallée Blanche on a perfect (bluebird) weekend there will be 800 – 1,200 descenders/day.

Saturday 11 Oct. 2025 (Day 5) - Visit Geneva

Today was divided into two parts, a morning visit to Musée d’histoire des sciences de la Ville de Genève (Museum of the History of Science of the City of Geneva), and an afternoon trip around the lake. In the evening there was a “end of tour” dinner.

The museum (above) is housed in Villa Bartholoni, a 19th century Palladian-style villa set in the park La Perle du Lac, with pleasant surroundings and views over Lake Geneva. It has a compact collection of early scientific instruments (e.g. astronomy, gnomonics, meteorology, microscopy, electricity, etc.). However it is an old-style museum with limited interactivity. I will admit I wandered through the rooms, and left after about 30-40 minutes.

I was on the lookout for things I had not seen in the past, or items that just caught my eye. For example, I saw an unusual apparatus for demonstrating ascending waterspouts (trombes d’eau ascendantes). It was created by Jean-Daniel Colladon (1802–1893) a Geneva physicist, and consisted of a rotating vane (moulinet à pales) in a large glass cylinder holding water. The upward spiral motion creates a visible “funnel,” much like a miniature tornado, and sawdust particles (sciure) were used to trace the flow lines, making the vortex structure visible.

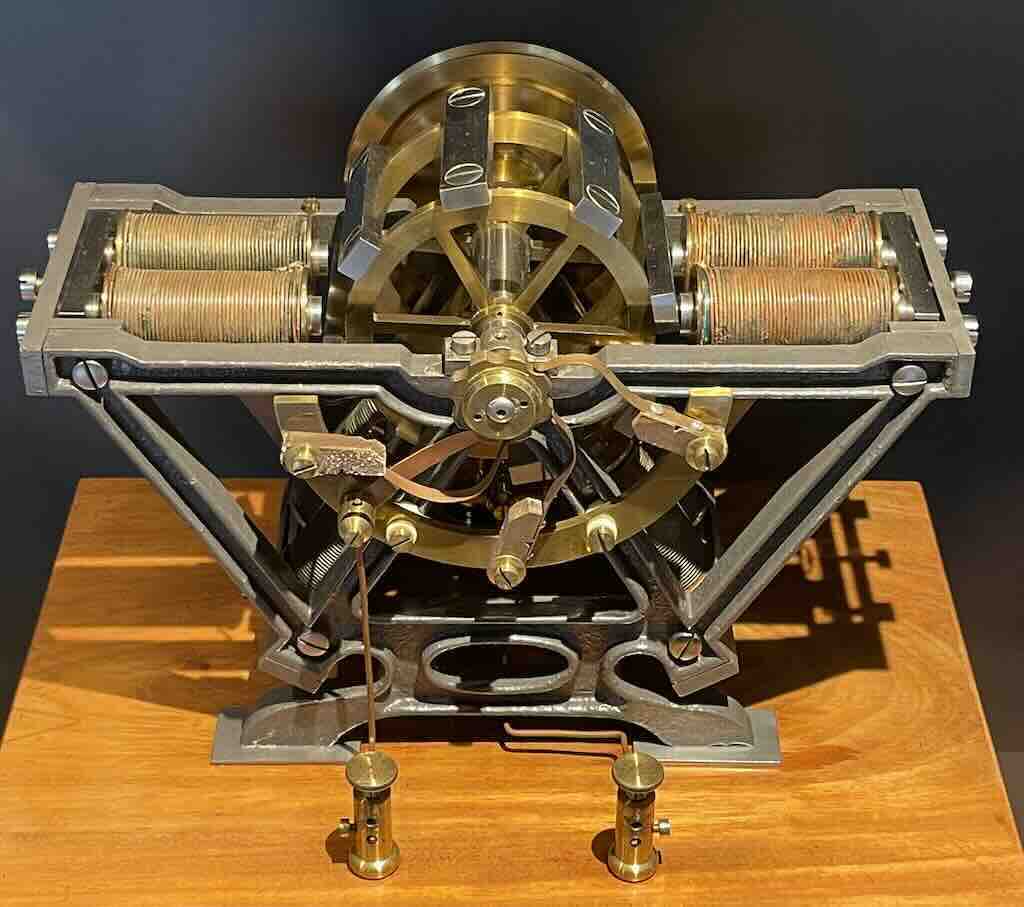

Not the most passionate item, but unusual. Next I saw a beautifully preserved “Gramme machine” (invented by the Belgian Zénobe Gramme in 1871), which was the first practical continuous-current generator and motor.

When connected to a direct current source, current passes through the coils and commutator, magnetising the armature in alternating polarity. The magnetic attraction and repulsion between stator and rotor poles produce rotation. So it’s a DC electric motor.

When driven mechanically (for instance by a belt or hand crank), it works in reverse as a DC generator, producing current at the terminals.

This is the kind of “modern” machine that a gentleman might have kept in his drawing room or study, and might occasionally have brought out after dinner to impress guests with his knowledge of the “new age of electricity”.

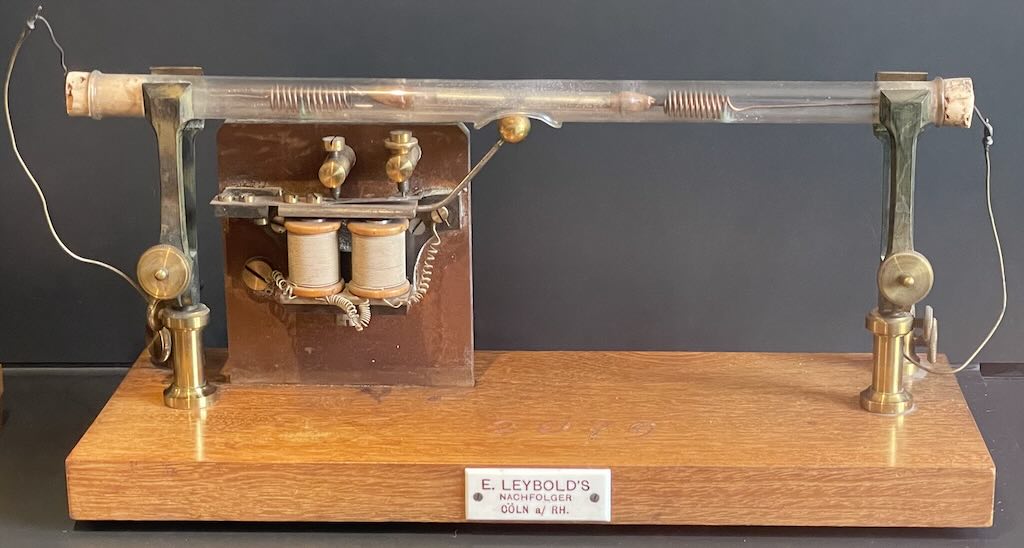

My next item was triggered by the name Leybold. They were my preferred makers of vacuum-tight components. I did not know that they made educational replicas and demonstration models into the early 20th century.

This equipment is a spark-gap resonator (also known as a Hertz resonator), an apparatus used in the late 19th century to demonstrate the existence of electromagnetic waves. So it was in fact an early proof of radio waves. Hertz proved James Clerk Maxwell’s theory (predicted in the 1860s) that light and electromagnetic radiation were of the same nature.

Prof. Charles-Eugène Guye was head of the Geneva university’s physics laboratory (ca.1908-1915) and an international authority on precision measurement. His instruments, such as torsion balances, electrometers, and electron tubes, were all handmade in Geneva, often by glassblowers and machinists working under his direct supervision.

I recognised this instrument immediately because I had built electron guns for low-energy electrons (<1 keV). His was for an energy range slightly higher (10 keV to 50 keV), but the electrons were produced by a different physical process. The Guye electron gun (sometimes called canon à électrons de Guye) was designed to emit and accelerate electrons in a vacuum using a cathode and one or more anodes. The idea was to measure their velocity from the accelerating potential, and observe deflection in electric or magnetic fields to determine their apparent mass.

By comparing measured deflection with theoretical predictions, Guye’s group tested whether the electron’s mass increased with speed, a central claim of Lorentz’s electrodynamics and Einstein’s 1905 special relativity.

Guye’s 1915–1916 results (with his students Charles Lavanchy and Stéphane Ratnowsky) agreed closely with Einstein’s relativistic formula, and the experiments were among the first quantitative confirmations of special relativity anywhere in the world. What they showed empirically was that mass was not constant but increased with velocity. This turned Lorentz’s and Einstein’s theory into measurable fact.

Guye’s electron gun transformed the cathode-ray into a quantitatively controlled electron beam, without which neither the electron microscopy nor the television would have matured so quickly. I think the example in the museum looked to be a later version made for laboratory demonstrations.

The afternoon was dedicated to a trip on the lake, which proved to be a disappointment. It was a 55 minute trip, without any commentary.

Dinner was in the restaurant Edelweiss. It’s a very traditional and well presented restaurant, including traditional music, etc.

The meal was a fondue bourguignonne, 200g of beef cooked in oil, homemade rösti and three sauces. It was a pleasant final evening, let down a little by the beef that I found not particular tender.