Wikipedia tells us that in Chinese poetry, a duilian (simplified Chinese: 对联; traditional Chinese: 對聯; pinyin: duìlián) is a pair of lines of poetry which adhere to certain rules. Outside of poems, they are usually seen on the sides of doors leading to people’s homes or as hanging scrolls in an interior. Although often called Chinese couplet or antithetical (contrasting) couplet, they can better be described as a written form of counterpoint. The two lines have a one-to-one correspondence in their metrical length, and each pair of characters must have certain corresponding properties. A duilian is ideally profound yet concise, using one character per word in the style of Classical Chinese.

In China, câu đối are known as 對聯 (duìlián), literally “paired couplets”. This art form has a long poetic tradition, emerging fully in the Song dynasty (960–1279). There were strict rules of balance, with the same number of characters on each side. Tones, grammar, and imagery was to be precisely matched. They were a central feature of Confucian scholarship and literary artistry, and could be seen on temples, ancestral halls, scholar’s studios, inns, and even New Year’s door decorations. Vietnam’s câu đối tradition is directly inherited from this Chinese practice, but over time, local elements like Nôm script and Vietnamese proverbs were sometimes added.

Chữ Nôm (often just “Nôm”) is a historical writing system for the Vietnamese language that uses Chinese characters (Hán) plus thousands of Vietnamese-invented characters.

In both China and Vietnam, a horizontal plaque (hoành phi/bian’e) would be paired with vertical couplets (câu đối/duìlián) to frame a sacred or honoured space. The horizontal plaque (e.g. sitting over a doorway) would include a name, virtue, or central concept, and the vertical couplets (e.g. on the sides of a doorway) would develop a poetic elaboration of ideals or blessings.

We can see in the feature image above that these panels can be very elaborate and decorative, but I will be looking as some very simple panels that may date from sometime between 1890’s to the 1910.

Vietnam adopted this system of panels, etc. during periods of Chinese cultural influence, particularly during the 1,000 years of Chinese rule (111 BCE – 938 CE) and reinforced during the Lý (1009–1225) and Lê (1428–1789) dynasties. This was probably due to the influence of Confucianism and its examination system, which brought to Vietnam these decorative forms because they were symbols of learning and moral order. By the 18th–19th centuries, hoành phi and câu đối had become so embedded in Vietnamese culture that local artisans specialised in them, producing distinctively Vietnamese carvings while retaining the Chinese structural logic.

Family History

My wife inherited three sets of panels, two sets will be shown here. My wife was a French national but born in Vietnam (Việt Nam), of French parents, but again both born in Vietnam.

The panels, in reality probably date from 1908 or earlier. A different panel has the date 1908 carved and gilded over an exiting Vietnamese script. One panel has my wife’s maternal grandparents name inscribed inside, suggesting that they came from Hanoi, or at least northern Vietnam.

Using Artificial Intelligence

I used ChatGPT to translate the first two panels (seen above). It immediately detected that the pair represented a 對聯 (câu đối), or moral couplet.

The initial translation was quite good, but hampered by the flat image of the carved, rounded script taken from a round “bamboo” pole. In addition there were a few character choices that reflected workshop tradition or transmission variants, which is common with altar carvings.

The initial translation was:-

- Right: To keep a household, hold to steady rules; keep chastity/frugality, and be fair, broad-minded, and forbearing.

- Left: For dealing with the world, there’s no special trick, just practice kindness/forgiveness, lenience, modesty, and humility.

The fact that the four core virtues for home and world were 公 (fairness), 忍 (forbearance), 恕 (forgiveness), and 謙 (humility), suggested that the panels might be copies of a traditional moral couplet.

It was possible to confirm that these panels belong to the hoành phi – câu đối ensemble used in northern Vietnamese ancestral halls and household shrines, typically black or red lacquer with gilded relief characters (sơn ta, thếp vàng). This exact format and finish are hallmarks of late–Nguyễn/colonial-era Hanoi craft (notably the Sơn Đồng guild area).

The next step was to look for a widely circulated classical moral câu đối, that would have been the inspiration for these panels. The full form is a known pair that appears across northern Vietnam and southern China in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Here is the standard form of this couplet:

Right pole: 居家有恒規 親可寬 鄰可恕

Cư gia hữu hằng quy, thân khả khoan, lân khả thứ

“At home, hold to steady principles: be magnanimous toward kin, forgiving toward neighbours”

Left pole: 處世無別法 忘勿怒 忍勿驕

Xử thế vô biệt pháp, vong vật nộ, nhẫn vật kiêu

“In dealing with the world, there is no other secret: forget anger, practice patience, avoid arrogance”

This was a classical maxim taught across East Asia. In Vietnam it became a staple of Confucian moral education, memorised by scholars and often displayed in homes.

Symbolic Importance

We have to imagine what the symbolic importance (hidden message) might have been to someone seeing these panels as they entered a private house.

Firstly the Nguyen dynasty still formally ruled Vietnam, but real power was in the hands of the French colonial administration after the Treaty of Huế (1884).

Secondly, Hán-Nôm (classical Chinese + Vietnamese ideograms) was still the script of the educated elite, while quốc ngữ (romanised Vietnamese) was only starting to spread among reformists and modern schools.

Thirdly, the Confucian civil service exams were abolished in 1919, but at the time these panels were hung the exams were still in place, though in visible decline.

Just hanging a pair of Hán-character bamboo câu đối said “This is still a Confucian household”. It would have been a quiet act of cultural resistance, asserting that Vietnamese tradition still held authority inside the home even if colonial power ruled outside.

So a câu đối at that time would have signalled a classical education, loyalty to tradition, and possibly a quiet resistance to colonial rule. Scholars might express loyalty to the Emperor, mourning for lost independence, or hidden critiques of French power through subtle metaphors that only educated readers could decode.

At that time, openly anti-French writing was dangerous. Câu đối allowed for layered meaning, for example a line praising the “Southern Dragon” could literally mean a family ancestor but secretly evoke Vietnam’s independence. Mention of dragon (long), phoenix (phượng), “Southern land” (Nam quốc), or “Imperial virtue” (hoàng đức) would suggest loyalty to the Emperor and quiet defiance of French authority. Just as mention of plum (mai), orchid (lan), bamboo (trúc), chrysanthemum (cúc), books (thư), or brush (bút) would suggest scholarship and learning. And reference to mountains (sơn), rivers (giang), “light returning” (quang phục), and mythical heroes would suggest resistance and nationalism.

So such panels would represent a safe wish for prosperity and virtue, and were a visible sign of education and virtue. But they could include a hidden patriotic message, legible only to the educated elite.

The reality was that French officials rarely understood classical texts. A household could publicly display Confucian ideals without censorship, but among Vietnamese elites, this would be instantly recognised as a refusal to surrender identity. It’s an interesting reminder that both my wife and her parents were born and educated in Vietnam, and would have been fully aware of the panels significance.

I wonder how my wife’s maternal grandparents, or even her great-grandparents who emigrated to Vietnam, obtained these panels. I also wonder if in bringing them back to France, they were just bring back some decorative items, or was that act also a hidden message.

It is strange that although my wife, and her parents, were born in Vietnam, I almost never heard them speak Vietnamese. My wife’s uncle, was also born in Vietnam, and only retired back to France in the late 70s (with his second, younger Vietnamese wife). The brothers often spoke together in Vietnamese, but would revert to French in company. Also when eating out in Nice, we only ever went to Vietnamese restaurants where my wife’s parents were always well received. But everyone spoke French. My wife’s father would disappear into the kitchen, and we never seemed to pay. I understood that my wife’s father often helped some of the local Vietnamese families navigate the complexities of home and small-business ownership.

The panels now hang in my living room, just as they hung in the apartment in Nice. A reminder of times past.

But the story does not end here.

We will see below that as we looked at the “bamboo” nature of the panels or poles, a new detail entered into the analysis.

Are They Really Bamboo?

My wife, and her parents, always spoke of the panels as being bamboo panels. But I must admit I just thought that it was more symbolic than a real statement about the material of the panels or poles. And I was right.

The poles are not bamboo, and they never pretended to be.

Of course, the idea of bamboo poles suggested a material that was accessible and resilient, and being a “humble” material fitted in with the idea of a household that wanted to preserve tradition without attracting too much colonial attention.

It is true that in northern Vietnam it’s been noted that some types of bamboo can reach 40 metres in height and 30 cm in diameter (i.e. under ideal conditions). For example, the “sweet bamboo” variety (a species used in Vietnam) is reported to potentially reach 25–30 metres in height and 13–30 cm in diameter under good conditions. It can be used for food (edible shoots) and for building quite substantial structures.

But, and there is always a but! Usually the nodes in the stem are especially clear and widely spaced, typically 30–45 cm apart, sometimes more in the fastest-growing sections near the middle of the culm. Polishing, with lacquering or painting, can visually hide them on the outside. But the hollowed inside of the half-cylindrical poles will always show the nodes because they are inherent characteristics of the nature of the growth of bamboo.

The challenge was now to look back to the period around 1900 in the region in and around North Vietnam. What kind of woods would be available and used? My friendly AI considered several woods commonly used for temple construction, ceremonial objects, and furniture. The options were Hopea odorata, Shorea, Manglietia/Parinari species, and Ficus/Banyan species (having eliminated giant bamboo).

My AI decided on Hopea odorata or Manglietia species. Both were abundant, culturally prestigious, and worked well for large hollowed ritual columns.

I had provided the AI with a photo of the interior of the poles, and it noted long, natural fibres (split and separated), no sign of laminates, and a rough interior surface, suggesting it was carved from a single trunk with hand adzes or gouges.

It also noted the trunks would have been selected from old-growth forest trees, which were common in northern Vietnam ca. 1900 before intensive colonial logging began. Also the craftsman had specifically chosen sections with minimal natural taper, often cut from the lower trunk near the roots, which tend to be cylindrical.

New Interpretation, New Significance

It was interesting that in formulating my query to ChatGPT I did not initially mention the size of these panels or poles. It assumed from the photos that the poles were the “usual” size, i.e. ~120–150 cm with a diameter of ~5–8 cm, and weighing ~3–5 kg each. This would be the size of traditional household câu đối. And even this size would be reserved for a wealthy, literate family, especially in northern Vietnam circa 1900–1915.

However these poles are 2.36 metres long, with a diameter of 20 cm. When hollowed out to make them portable, and carved with a moral inscription, they were more likely used for public display or processions. They might have been used to flank an altar or temple gate, or eventually mark the entrance to a family compound during ceremonies.

However poles decorated in black lacquer with gold-painted inscriptions suggest visible ceremonial objects designed to signify authority, reverence, and connection to the Confucian or Buddhist elite traditions.

The size and decoration meant that they were expected to be read from a distance, probably standing at a temple entrance, ritual gate, or central courtyard during festivals. And they would have been expensive to make, suggesting a wealthy sponsor, either an important village association, or elite family.

The gold paint looks evenly applied, and there don’t appear to be any old chisels marks, suggesting that the texts are original. We do not see any Vermilion lacquer, thick gold leaf, carved dragons, phoenixes, etc. so they are not from Imperial gates, but nor are they unpainted or plain painted wood, which would have suggested a local shrine or festival.

The likely origin would be a temple or ancestral hall with substantial resources, but not part of the imperial bureaucracy itself.

Its possible to try to read far more into such poles, and ChatGPT is good at developing a reasoning approach (sometimes ill conceived, but occasionally difficult to refute).

The size and decoration of poles would suggest that they were to read by many, possible in a communal context. The inscriptions, about constancy in the family and forgiveness in society, was perfectly suited to such a context. In the colonial context, the text would be seen as non-political on the surface, but symbolically it declared Vietnamese Confucian values in a public, visible way.

In other words, these poles were physical embodiments of traditional authority, standing literally and figuratively against the forces of colonial modernisation.

This interpretation might be challenged, because it’s not sure how many of those viewing the poles would have had a Confucian education, and have been able to read and understand the text. Nevertheless displaying the poles in a communal setting would have shouted very publicly the erudition and legitimacy of a family, and reinforce their claim to cultural authority.

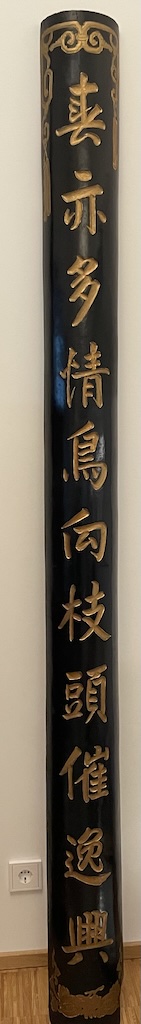

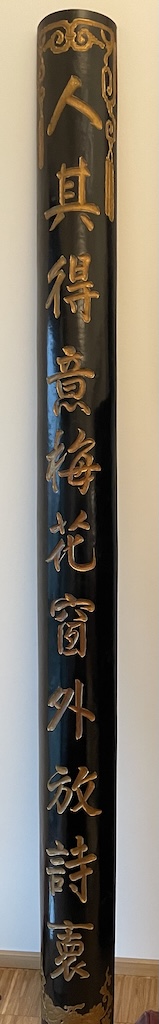

Another Pair of Poles

Here we have a differs pair of poles making up another duìlián (câu đối). However, the couplet is completely different, and the location in a house would also be completely different.

This poetic duìlián can be found in multiple proverb/couplet anthologies, although no single named author is given.

There are at least two reliable references that print the couplet exactly in this form, sometimes with minor cosmetic variants.

A polished translation is:-

Right pole: 人其得意,梅從窗外放詩懷

nhân kỳ đắc ý, mai hoa song ngoại phóng thi hoài

“When one is in fine spirits, the plum beyond the window releases a heart full of poetry”

Left pole: 春亦多情,鳥向枝頭催逸興

xuân diệc đa tình, điểu hướng chi đầu thôi dật hứng

“Spring too is full of feeling; birds upon the branch-tips spur untrammelled inspiration”

The reading (spoken aloud) is in Hán-Việt, not modern Mandarin. However, the couplet is well known also in Mandarin as:-

rén qí dé yì, méi huā chuāng wài fàng shī huái

chūn yì duō qíng, niǎo xiàng zhī tóu cuī yì xìng

As with the first pair of poles the written characters are Chinese, but the spoken form is local. In fact a household in Hanoi with a Confucian altar or study would never have spoken Mandarin, even though a modern Chinese speaker can read the same characters. Both the first “moral” set of poles and this second “poetic” set belong entirely in the Hán-Việt world.

For both sets of poles the characters at the same position in each line should match in tone, grammar, and meaning. Here we have the example with “plum blossom” on one side, and “spring bird” on the other.

This second pair is literary and poetic, celebrating nature, spring, and poetic inspiration.

Together the two sets form a perfect late-Nguyen/colonial Hanoi ensemble, with one set speaking of duty and ethics, the other of refined culture and joy.

The first pair would have been kept near an ancestral altar or in a main household hall. This pair is decorative and literary, and would have been perfect for a study, reception room, or space for quiet reflection. They would also go well in a space reserved for entertaining friends with tea and poetry.

Ir’s worth noting that my AI provided a text taken from printed collections. Where the character 梅 (plum) sometimes appears simply as 梅, while on this pole there is mention of 梅花 (plum blossoms). This is a workshop embellishment, and does not change the mean of the couplet.

My friendly AI also mentioned that the couplet has classic balance with plum blossoms and spring birds, and later poetic heart with soaring inspiration.

It noted that couplet echoed a famous Tang dynasty line by Li Bai:

俱懷逸興壯思飛

“Together we harbour soaring inspiration and heroic thoughts that take flight.”

So this reference links it to high-literary diction, but the exact two-lines formed here are a later, anonymous creation.

These poles are formal, high-status decorative objects, not casual decorations. Their size, craftsmanship, and poetic theme all point to them hanging in the reception or study hall of a wealthy literate household or a temple-style family home in northern Vietnam (Hanoi and Red River Delta) around the late 19th or early 20th century.

They would have been hung to very visible, so that visitors would immediately read them and know the owner was a man of learning and high-culture.

Unlike the first set of poles, these would not be seen in public, they were personal and literary, not explicitly religious or civic.

My AI in closing took the time to stress…

Plum blossoms (梅花) → purity, resilience, scholarly integrity.

Birds (鳥) → joy, vitality, the voice of spring.

Poetic feelings (詩懷) and untrammelled inspiration (逸興) → the inner life of a scholar.

Together, they link the natural world to intellectual creativity, reinforcing the household’s claim to refined taste and learning. In practice they would normally have been found in a mandarin’s house, or with wealthy merchant wanting to stress his knowledge of classical literature, or possibly in the public room of a large clan residence.

In Vietnamese terms, this is văn hiến (文獻), or the cultivated harmony of literature, morality, and nature.