This is part-1 of a 2-part report on my trip (July 2025) to Svalbard in the Arctic on the Quark Ocean Explorer. Here is the full list of my posts:-

- Travel – Planning a cruise to the Arctic

- Hotel – Hilton Airport, Helsinki

- Places – Arctic I

- Places – Arctic II

- Travel – Quark Ocean Explorer

Before my Arctic trip I also decided to visit Helsinki, and I stayed in Solo Sokos Hotel Torni. After my trip I returned to Helsinki and stayed in the Hotel Kamp.

One of the most impressive aspects of the cruise was the professionalism of the team of explorer experts. During the trip everyone was invited to register to receive a collection of photos and a video of our explorer cruise. Three weeks after arriving back home we all received access to a >20GB dropbox archive, including a 16 minute video. My Arctic trip report includes a few of my photos, and some excellent wildlife photos taken by the explorer team.

Also throughout this trip report, I will occasionally reference the trip I made to the Antarctic (late Nov. to early Dec. 2024). The best entry point for my trip report is “Travel – Antarctic on Le Lyrial (Days 1-7)“.

Arctic - what does it mean?

The word Arctic comes from the Greek word arktikos (ἀρκτικός), meaning “near the Bear,” a reference to the constellation Ursa Major (the Great Bear), which is prominent in the northern sky. This name has been used since antiquity to refer to the far northern regions of the Earth.

The Arctic is generally defined as the region around the North Pole, encompassing the Arctic Ocean and parts of eight countries, namely the United States (Alaska), Canada (Arctic Archipelago), Denmark (Greenland), Iceland (Grímsey), Norway (Nord-Norge and Svalbard), Sweden (Lappland), Finland (Lappi), and Russia (Far North).

There are two main ways to define the Arctic, either everything north of the Arctic Circle (66°33′ N latitude), or areas where the average July temperature is below 10°C (includes subarctic zones and better reflects the treeless tundra biome).

The term “Arctic” was used loosely until the 19th and 20th centuries, when the science of the polar regions began to formalise climatic and latitudinal boundaries. As oceanography, climatology, and ecology developed, definitions became more refined. Institutions like the Arctic Council (formed in 1996) now use criteria that include ecological vulnerability and indigenous population presence.

The Arctic has been home to indigenous peoples such as the Inuit, Sámi, Chukchi, and Nenets for thousands of years. These groups never “discovered” the Arctic, they simply lived and thrived there long before European exploration.

European exploration began in earnest in the late Middle Ages (9th–12th centuries with Norse explorers (e.g. from Iceland and Greenland) who reached parts of the Arctic, including the coasts of Greenland and Labrador.

In the 16th century, European nations, notably England, the Netherlands, and Russia, began searching for a Northwest Passage to Asia.

In the 19th century Expeditions like those of John Franklin (lost in 1845) intensified Arctic exploration.

And in the 20th century, early air exploration, icebreakers, and eventually satellite mapping completed much of the Arctic’s geographical charting.

But is was only in 1969 that the first confirmed surface journey to the North Pole was made by Wally Herbert.

Modern Arctic tourism is a growing but tightly regulated industry due to environmental concerns and infrastructure limits.

What is Svalbard and where is it?

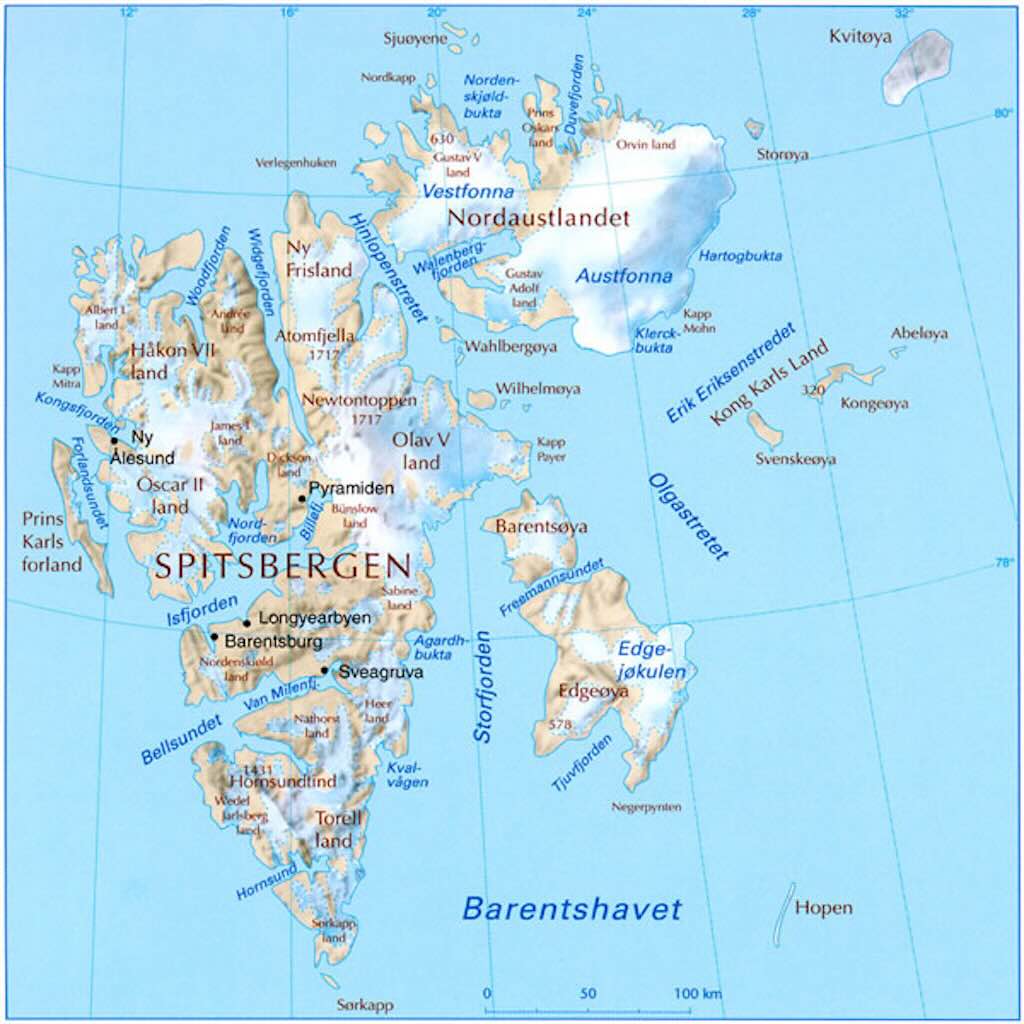

Svalbard is a remote archipelago located in the Arctic Ocean, about halfway between mainland Norway and the North Pole. It is under Norwegian sovereignty and governed according to the Svalbard Treaty of 1920, which grants certain rights to citizens of signatory countries but confirms Norway’s full authority over the territory.

The archipelago consists of several islands, the largest of which is Spitsbergen, home to the main settlement, Longyearbyen. Other inhabited areas include Barentsburg (a Russian mining community) and the research settlement of Ny-Ålesund. Much of the land is covered by glaciers, and the environment is dominated by arctic tundra and permafrost.

Svalbard is known for its extreme conditions, including long, dark winters and continuous daylight during the summer. It is home to polar bears, walruses, Arctic foxes, reindeer, and seabird colonies. Economic activities include coal mining, scientific research, and tourism. It also hosts the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, an international project that stores backup copies of the world’s crop seeds in a secure facility within a mountain.

What should we see when we look at the above map:-

Firstly, the largest island is Spitsbergen, where nearly all settlements are found. The other islands, i.e. Nordaustlandet, Edgeøya, Barentsøya, etc., are vast, icy, and mostly uninhabited.

Many of the place names are in Norwegian, but others are Russian, Dutch, English, and German, and echo the passage of whalers, explorers, and miners.

Unlike Greenland or northern Canada, Svalbard has no indigenous peoples. However, The Svalbard Treaty of 1920 allows citizens of all signatory countries to live and work there, without visas or residence permits. And (as of 2025) the 48 are Afghanistan, Albania, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, China, Czech Republic, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Egypt, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, India, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Monaco, Netherlands, New Zealand, North Korea, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Serbia, Slovakia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States and Venezuela. Remember, Svalbard is Norwegian territory, just one with special treaty obligations. So the treaty does not grant political rights (e.g. voting in Norwegian elections), but it does protect economic and residency rights in Svalbard.

Svalbard is often treated as a “visa-free zone”, but that only applies to entry to the archipelago, not transit through mainland Norway. So travellers may need a multi-entry Schengen visa to transit through mainland Norway to get to and from Svalbard. In fact the Norwegian government controls immigration to Svalbard indirectly, by limiting access via flights and infrastructure from mainland Norway.

There is no social welfare system on Svalbard. Anyone who cannot support themselves may be deported to their country of citizenship, regardless of treaty rights. And remember, Svalbard is not a sovereign state and does not have its own nationality (so it does not issue passports).

There is the catchy phrase, “it’s illegal to die in Longyearbyen”, but it’s not factually true. You can certainly die there. But the local hospital can’t handle serious or end-of-life cases. So typically, terminally ill residents and anyone close to death are sent to the Norwegian mainland for treatment or to pass away. And since the 1950s, burial in Longyearbyen has been banned. The town’s permafrost is so deep that bodies simply don’t decompose, and decades-old graves still preserve organs.

Again its often stated “even deadly viruses like the 1918 influenza” survive. Which is again not true. What is true is that in 1918, seven miners who died of Spanish flu were buried in permafrost at Longyearbyen. Researchers later used ground-penetrating radar to locate their graves about one metre below ground. These bodies were indeed well-preserved due to the permafrost, but no viable influenza virus was ever extracted from them. There have been no reports of anyone recovering live virus or infectious particles from the Svalbard graves.

What is true, is that in Alaska’s Brevig Mission, a pathologist named Johan Hultin exhumed bodies from a 1918 permafrost grave in 1997. From one victim, known as “Lucy”, researchers successfully extracted genetic material (RNA) from the 1918 influenza virus, but the virus itself was not alive or infectious.

So since about 1950, burials in Longyearbyen have been banned. However, cremations can be performed on the mainland, and it’s possible to bury ashes (urns) at Longyearbyen cemetery, but only with special government permission. The process involves obtaining a state license for cremation and burial of ashes, which can take some time.

It is not true that “giving birth on Svalbard is illegal“. It’s true that expectant mothers are strongly advised to leave the island ahead of due dates. This is not because births are illegal, but because medical facilities are minimal and childbirth complications cannot be managed locally. Pregnant residents and visitors are typically required to leave the island by the 37th week of their pregnancy to ensure they can give birth on the mainland where full medical support is available. In fact it is perfectly possible to be born on Svalbard, but it does not give the child the right to live there permanently. The territory is under Norwegian sovereignty, but no one (not even Norwegians) has the right to settle permanently. Residency is dependent on employment, health, and self-sufficiency. The child would be registered in Norway, but this confers no special status or citizenship beyond regular Norwegian law.

It is true that Svalbard enforces a ban on cats. Svalbard has no native land mammals other than the Arctic fox and reindeer. Remember polar bears are classified as marine mammals because of their reliance on sea ice for hunting and survival. Introducing cats poses a serious threat to local bird populations and the fragile Arctic ecosystem. Cats could easily prey on nesting birds and/or spread disease. It is said that Kesha, a ginger cat in Barentsburg (the Russian settlement on Svalbard), was registered as a fox to skirt regulations (he passed away in early 2021).

It was once stated that Ny-Ålesund has no mobile phones or wi-fi. The justification was to prevent interference with highly sensitive geodetic and atmospheric equipment run by the Norwegian Mapping Authority. However Telenor installed the world’s northernmost 4G cell tower on November 28, 2023, enabling mobile calls and data access. So now mobile phones work for calls, SMS, and mobile data. However there is still a strict ban on wi‑fi and Bluetooth devices (2–32 GHz range), extending over Ny-Ålesund and a 20 km radius surrounding it. All visitors and staff are required to turn off wi‑fi and Bluetooth, and airplane mode alone is not enough.

Normally airplane mode cuts wi-fi and Bluetooth as well, but Bluetooth can emit low energy pings (if re-enabled), wi-fi can still perform background scanning, some phones have NFC (Near-Field Communication), and they contain internal oscillators, which can leak from clocks or components. So this actually means that no transmitting electronics are allowed within several kilometres of sensitive equipment. So phones, smartwatches, tablets, and wireless earbuds must be completely powered off, not just in airplane mode. Some researchers go further and use Faraday bags or leaving electronics in designated storage areas. And yes, signals can often be traced to a specific location or even to a person.

Firstly, the Norwegian Parliament, via local regulators, declared Ny‑Ålesund and surrounding areas (within ~20 km) a “radio‑quiet zone” for frequencies from 2 to 32 GHz since 1994. That ban includes wi‑fi, Bluetooth, drones, and most radar/4G/5G devices (this includes cruise-ship wi‑fi). There are in fact three reasons for this ban:-

- Geodetic observatories (VLBI & GNSS): Ny‑Ålesund hosts two bore-sited VGOS telescopes. VGOS stands for VLBI Global Observing System, and bore-sited means “bore-hole” foundation anchors that extend several meters into the ground, reaching stable layers and helping isolate the structure from permafrost movement, etc. There are two separate telescopes Nn and Ns, that are about 1.5 km apart, though still close enough to operate as a coordinated VLBI pair. VLBI is a technique where radio telescopes all over the world observe simultaneously the same distant quasars (extremely bright, stable radio sources billions of light-years away). By comparing the tiny time differences when the signals arrive at each telescope, scientists can calculate the distances between telescopes with millimeter accuracy.

This allows researchers to measure Earth’s rotation, wobble, and axial tilt. They can track continental drift, and also define and maintain the International Terrestrial Reference Frame (ITRF) which supports satellite navigation systems (e.g. GPS, Galileo).

-

Atmospheric and climate sensing (LIDAR, SLR): are instruments that measure aerosol concentration and/or tracking satellites. The lasers are extremely vulnerable to RF noise, including emissions from wi‑fi and Bluetooth.

-

Satellite communication and monitoring stations: The GFZ operated X‑band (microwave) satellite receiver cannot transmit its own signals and only receives faint signals from orbiting instruments, and any local RF spill can render that impossible.

There are no inter-settlement roads on Svalbard. Travel between communities is only possible by snowmobile, boat, plane, or helicopter, depending on the season. Whilst snowmobiles do not require roads between settlements on Svalbard. They operate off-road across snow-covered tundra, glaciers, and frozen fjords, but only in winter and on designated or permitted routes. These aren’t “roads” in any constructed or paved sense, just mapped tracks over snow and ice, often marked with sticks or signs in season. It does mean that navigation is critical, and GPS, maps, and satellite beacons are standard. Svalbard has strict environmental laws, so you can’t just ride anywhere. Snowmobiles may only be used on approved terrain.

Then there are a few unusual laws, limits and habits, namely:-

- Locals have monthly quotas for alcohol purchases and must use rationing‑cards. It’s enforced under the “Alcohol arrangement for Svalbard” regulations. Visitors must show a return flight ticket to buy beer or liquor, even self-checkout is off‑limits. The quota is up to 2 bottles of spirits (over 22% ABV) or 4 bottle of fortified wine (e.g. port, sherry, between 15–22% ABV). And 24 half-litre cans/bottles per month of beer. And normal wine in “reasonable amounts”. So technically unlimited, but monitored.

- Historically Svalbard’s modern settlement began with coal mining communities in the early 20th century, and the Norwegian authorities introduced alcohol quotas to control heavy drinking among male labourers, many of whom lived in isolated and extreme conditions for months at a time. The rationing system was meant to preserve order, health, and safety in a harsh and remote environment.

- The Governor of Svalbard states clearly that anyone venturing beyond town boundaries is legally required to carry suitable means to scare off polar bears. “Suitable means” may include flare guns, thunder flashes, etc. Additionally, Svalbard authorities strongly recommend that travellers also bring a rifle for optimal protection. Both the Governor’s firearms guidelines and UNIS (the University in Svalbard) state that rifle plus flare gun is expected when venturing outside town. Many visitors consider it essential to rent or borrow a rifle (plus flare gun) before leaving Longyearbyen. Getting a permit is required, but local outfitters/guides are able to arrange this. Inside town, there are gun-lockers at hotels, shops, and cafes where guns must be stored while indoors.

- Nearly every man-made object from before 1946, including seemingly insignificant fragments like tin can scraps or old ammunition casings, is strictly protected by law and must not be removed or disturbed. Under the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act (2001), all cultural heritage remains, including buildings, installations, single objects, graves, bones, etc., dating from 1945 or earlier are automatically protected. In addition each protected object has a 100-meter buffer zone prohibiting disturbing, removing, or damaging “anything”. The law doesn’t allow exceptions, so tourists and locals alike must leave every item exactly as found, regardless of how trivial it seems. Even items that appear to be just garbage may be cultural heritage, protected under law.

- Within national parks, motor vehicles are banned on bare ground, but snowmobiles are permitted. Cycling is prohibited, even on established paths.

- Since April 1, 2007, every person (including tourists) arriving in Svalbard pays a 150 NOK environmental tax, which is automatically added to plane or cruise tickets. It pays for wildlife and ecosystem monitoring, cultural heritage preservation, and environmental restoration, research, and education projects. Residents are eligible to have the fee refunded.

- Cannabis is classified as an illegal narcotic under Norwegian law, which applies to Svalbard. Possessing up to 15 g can lead to significant fines, and anything beyond carries risk of prison or even removal from Svalbard (there is no prison on Svalbard).

- In Svalbard, there are steep fines (1,000’s of € or $) for disturbing wildlife, especially iconic Arctic species like polar bears and walruses. It is illegal to “entice, pursue, or by other active actions seek out wildlife” in a manner that disturbs them, regardless of distance.

- Under the Svalbard Treaty and the Svalbard Act, Norway is only allowed to tax residents to cover the cost of services there. As a result, Svalbard (including Longyearbyen) has no Value-Added Tax (VAT), which makes many goods and especially alcohol cheaper than on the mainland. Residents pay a flat income tax of around 8% on employment income, significantly lower than the roughly 22–25% rate common on mainland Norway.

- Carrying loaded firearms within settlement areas is illegal (including in vehicles or on snowmobiles). All firearms must be carried unloaded, with a bolt removed or visibly open, making it obvious they contain no ammunition. Everyone must demonstrate that the firearm is empty to any authority or passerby. And it is against regulations to bring firearms into shops, public buildings, or indoor spaces in Longyearbyen.

- Finally it is still possible to send mail to the North Pole. Longyearbyen’s post office regularly handles mail addressed to “Santa Claus, North Pole”, and they answer some, especially from children.

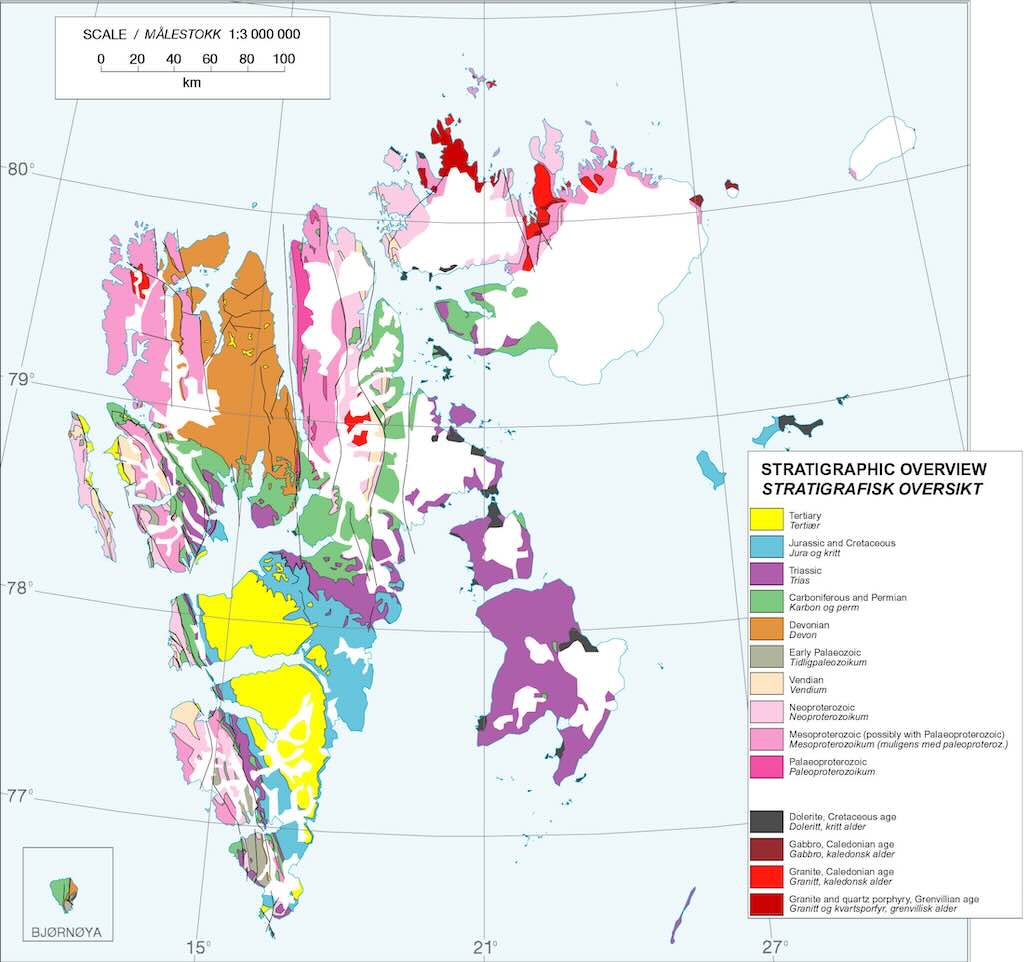

Svalbard - Atlas of Earth’s Deep Past

Svalbard contains rocks from nearly every major geological era, from the Precambrian (over 1 billion years old) to the Cenozoic (present-day).

The above map visualises this. With the colour-coded units on the map we can see how stratigraphic units from different time periods are exposed across the archipelago.

This is exceptionally rare on Earth, and few other places offer such a complete and accessible stratigraphic sequence.

The archipelago showcases a wide range of geological processes that occurred more or less sequentially:-

- Tectonic collisions – Svalbard’s basement rocks were deformed and metamorphosed over 400 million years ago during the Caledonian orogeny (490–390 Ma), when Laurentia and Baltica collided to form a vast mountain belt (consisting of multiple mountain ranges).

- Rifting and passive margin development – Following the Caledonian uplift, Svalbard experienced extensional faulting and subsidence, forming a passive margin where thick sedimentary sequences accumulated through the Devonian (419.62 Ma to 358.86 Ma) to Carboniferous (358.86 Ma to 298.9 Ma).

- Glacial and interglacial sedimentation – During the Quaternary (2.58 Ma to present), Svalbard was repeatedly glaciated, leaving behind moraines, tills, and layered marine sediments that preserve a detailed record of ice advance and retreat.

- Carboniferous coal-forming swamps – In the late Paleozoic (359 Ma to 252 Ma), Svalbard lay near the equator, and tropical peat swamps formed extensive coal seams, which are especially visible in the Central Basin of Spitsbergen.

- Permian evaporite basins – During the Permian (298.9 Ma to 251.902 Ma), arid conditions and restricted marine basins led to the deposition of thick evaporites, including gypsum and anhydrite, particularly in the Tempelfjorden Group.

- Mesozoic marine transgressions – The Triassic (251.902 Ma to 201.4 Ma) and Jurassic (201.4 Ma to 143.1 Ma) saw repeated sea-level rises that flooded Svalbard, depositing fossil-rich shales and sandstones in shallow marine environments teeming with ammonites and marine reptiles.

- Cenozoic faulting and uplift tied to the opening of the North Atlantic – As Greenland and Eurasia drifted apart in the Paleogene (23.04 Ma to 2.58 Ma), Svalbard was faulted and uplifted along the West Spitsbergen Fault Zone, creating the rugged mountains and fjords seen today.

Remember, you cannot legally take away rocks, fossils, or any other natural or cultural objects from Svalbard, even seemingly ordinary ones like stones or shells.

Svalbard functions as a natural geological textbook. Not only because of the completeness of its record, but also because it shows transitions clearly (e.g. how ancient mountain belts evolve into sedimentary basins). It offers clear lessons in plate tectonics, e.g. you can read the opening and closing of oceans, the formation of mountains, and the laying down of coal and oil-bearing strata.

If you fancy following up on the geology of Svalbard check out:-

Frozen Fossils: A History of Life in Svalbard

From Svalbard trilobites to plate tectonics: A lifetime in palaeontology

Svalbox – An interactive portal providing Svalbard’s geoscientific data

2 July 2025 (Day 0)

Day 0 was about “signing in” for the explorer cruise. They persisted throughout the trip in called passengers “ocean explorers”, which I found a bit ridiculous.

The instructions were clear. Turn up ready, packed, etc. at between 14:00 and 19:00 on 2 June 2025 in the Hilton at Helsinki Airport.

The first thing was to complete and sign the “Quark Health Declaration Form”.

I was given a planning for the next day, 3 June 2025, as well as luggage/cabin tags for suitcases. It was interesting in that my suitcase weighed 14 kg, and the comment was immediately “your travelling lite”. My backpack was 4 kg, and I distinctly remember being warned that the limits were 20 kg and 5 kg respectively, with no option for excess baggage. Despite this, it was evident that a number of my fellow passengers ignored that rule. On top of that I actually didn’t use all the stuff I had packed.

Surprise-surprise, I had been upgraded from a simple “porthole” cabin (N°310) to cabin N°408 (a Deluxe Veranda Stateroom).

This was a change from 15.4 square-metres with a porthole (actually just a window), to 19 square-metres with a floor-to-ceiling window and a walk-out balcony. This represented a 30% markup on the price I paid.

First thing, I was put in one of three groups, mine was green Group 3. Beyond just walking together to the airport, and tagging the luggage, it didn’t have any significance onboard the ship.

Points worth noting were that the flight time was approximately 3 hours, and that everyone would have around two hours free in Longyearbyen after arriving and before boarding the ship. But that luggage would be transferred directly from the airport to the ship.

Point of comparison with my Antarctic Ponant cruise, was that with this cruise there was no evening meal included for passengers. That meant that I had no opportunity to say hello to my fellow travellers. With the Ponant cruise, on that first evening, everyone sat together on round tables that could take 10-12 people. I met several people that would become travel buddies, and even today we still message each other on our WhatsApp group.

This time I had not eaten all day, so I had a beef burger and a small beer in the hotel restaurant (cost €28 including tip).

The Ocean Explorer itinerary

What you book for is a provisional, or ideal, itinerary. but changes can be made due to weather, wildlife spotting, etc.

Above we have the actual itinerary of our cruise, including the different kinds of excursions, and any important wildlife spotting’s.

3 July 2025 (Day 1)

Today was really in two parts, getting to the cruise ship harboured in Longyearbyen, and boarding, with all the usual first-day, on-ship formalities.

According to the planning, breakfast was served in the Hilton Airport Hotel between 06:00 and 10:00.

Again on my Ponant Antarctic cruise everyone had breakfast together, sitting at those same round tables, so it wasn’t surprising that groups would start to form.

Luggage, properly tagged, had to be in the lobby at 07:30, and porters took the luggage to the check-in counter at 07:50.

The green Group 3 meet and walked to the airport at 09:10.

We had to collect our luggage, and check-in individually for the charter flight Enter Air ENT 512. I had never heard of them, but they are a Polish charter airline, founded in 2009, and operating 34 aircraft.

The scheduling was impressive, and we had only to wait a few minutes to check-in, and passport control was automatic and security was very fluid.

The gate was 51A in the non-Schengen part of the terminal. The walk from the hotel to the airport check-in took about 8-9 minutes. Then, inside the airport, the gate was over behind the hotel we had just stayed in, so another 10 minute walk brought us to out gate were we could see the same hotel from the other side.

Neither walks were particularly challenging, but Gate 51A was in part of the airport that looked like it was almost never used. We were the only passengers in that area of the terminal, and all the shops but one, were closed. Gates 50 and 51 looked like they were dedicate to charter traffic.

One thing I had never seen before was that near the Gates, there was a Pet Relief Area. It provides “a private and secure space for pets”, and also features “artificial turf and waste disposal facilities”.

During check-in we learned that we were 98 passengers, and so things would not be crowded. In fact, the organisers managed to sequence things so that we had virtually no delays.

We would later learn there were 50 US passport holders, 18 Australians, 16 from the United Kingdom, 3 Germans, 2 people from Canada, China, and Hong Kong, and one person from Belgium, Korea, Luxembourg, Singapore and Spain. And as a group our average age was 58, which made me feel quite old. Fortunately there was onboard a 91-year-old gentleman, which was an excellent example that even elderly people with limited mobility can go on explorer cruises. A fact that did not make me feel any younger. Its also worth noting that in the crew the dominant nationalities were Filipino and Indonesian.

The airplane was nearly half-full, so I had a window seat 30F and an aisle to myself. There was nothing much to say about the flight, there was some initial turbulence, and they did serve a drink (water in my case), but that was about it.

Just as an aside, I noticed that on one of the fore cabinets there was a red sign “Smoke Hood“. I don’t think I having ever noticed this before. Commercial aircraft carry multiple smoke hoods (usually one at each crew station, plus extras near fire-prone areas like galleys and lavatories). They are often not signed on storage units, but they are part of the crew’s emergency fire response equipment, and all cabin and cockpit crew receive mandatory training on how to use them.

Svalbard Airport, Longyear (often called Longyearbyen Svalbard Airport), has the IATA code LYR and ICAO code ENSB.

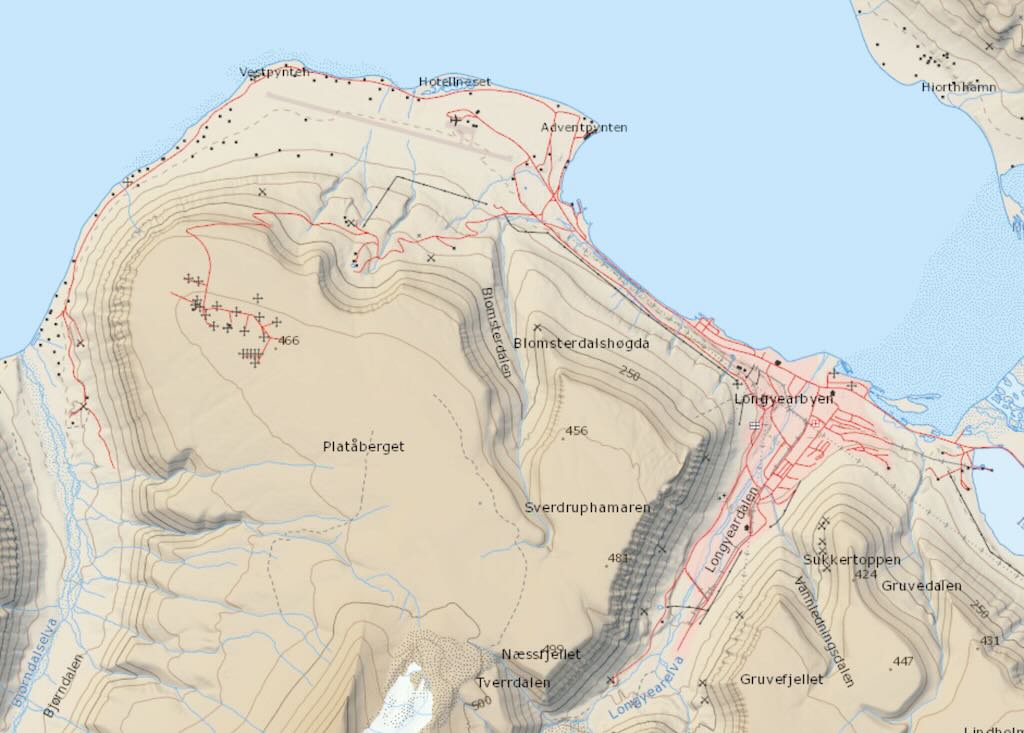

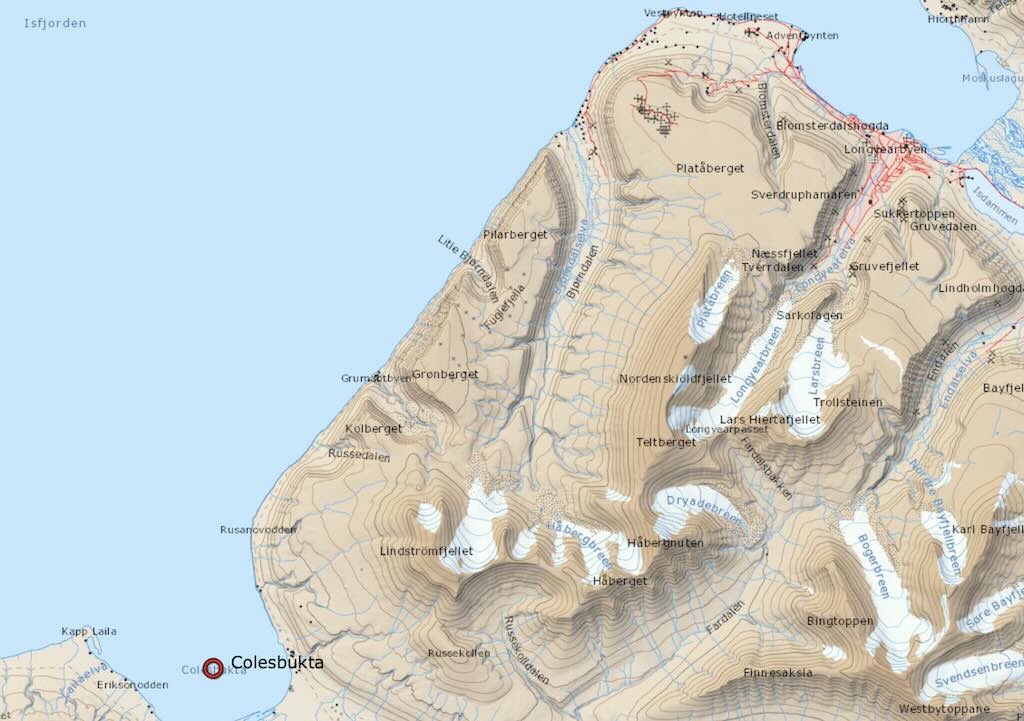

The airport is located about 3 km northwest of Longyearbyen, on the peninsula of Hotellnese, and is the northernmost airport in the world with scheduled public flights.

Svalbard Airport is a very small airport, but there was a simple but efficient passport control. Its worth noting that Finland joined Schengen in 2001, and Norway, although not an EU member, entered Schengen through an association agreement implemented also in 2001. So travelling between Finland and Norway would normally be without internal passport controls. However Longyearbyen (Svalbard) is not part of the Schengen Area. It is in fact governed by the Svalbard Treaty and, despite being part of the Kingdom of Norway, is outside both the European Economic Area (EEA) and the Schengen Area. They are also outside the Nordic Passport Union, although Nordic citizens can live and work there freely by treaty.

Technically Svalbard has its own visa-free status. However, if some nationalities did require a Schengen visa to travel via mainland Norway, they would then require a visa for multiple entries.

We boarded one of three coaches, that took everyone into Longyearbyen. We were left in the town a good two hours, before again being picked up for the trip to the dock, and our ship.

On the short drive in, there was a guide that introduced us to the island and the town of Longyearbyen (population 2,000–2,500 people, depending on the time of year). The local agent was Hurtigruten, or more specifically Hurtigruten Svalbard, a tour and hotel company based in Longyearbyen.

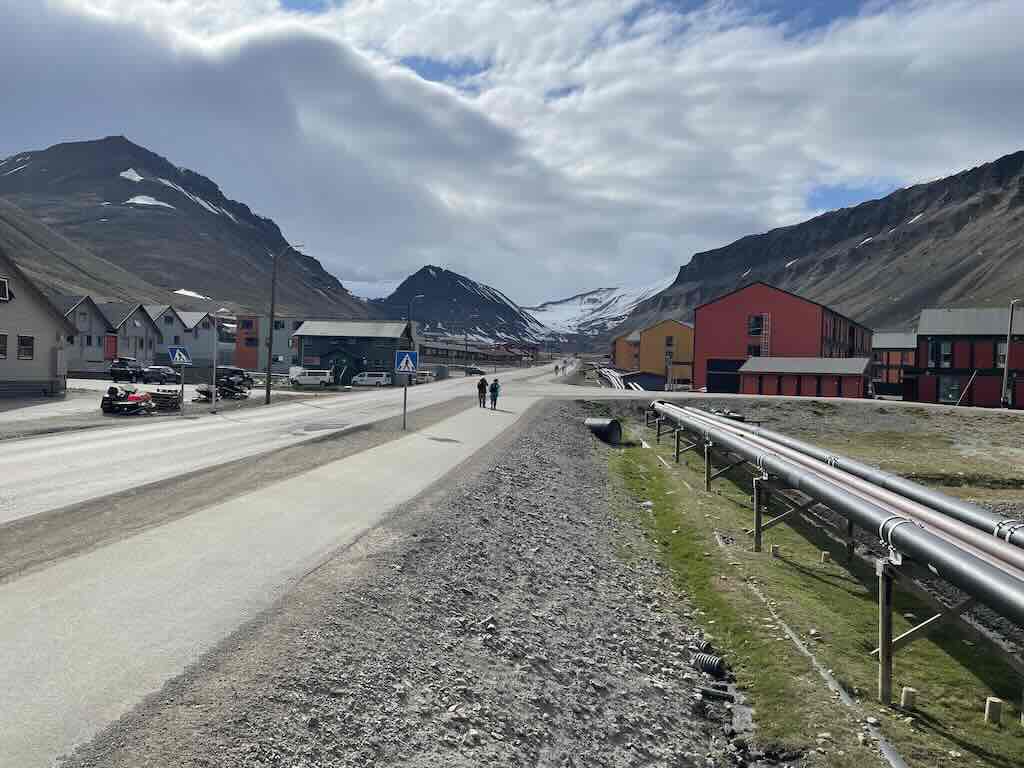

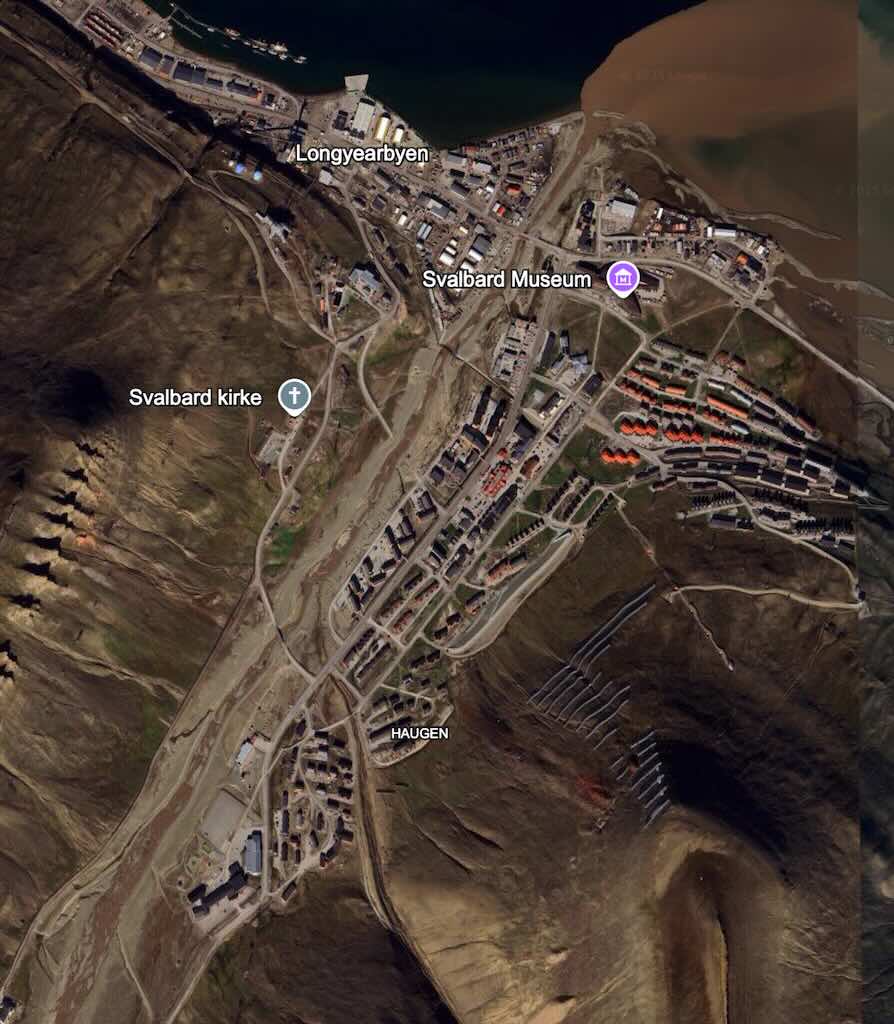

Longyearbyen stretches along a narrow valley (Adventdalen) surrounded by steep Arctic mountains. The built-up area is linear, with most services within walking distance of each other. We can see below a central free parking area, and a “pedestrian-friendly zone” called “Sentrum”, where shops, restaurants, and hotels cluster. Everywhere appeared to be “pedestrian-friendly”, and I guess the town has all the usual amenities, but probably no more than one of each (except facilities for tourists).

Residential areas are spread out along branching roads, and all the buildings appear functional, minimalist looking, boxy, often colour-coded, and raised off the ground. Services are also raised of the ground, presumably because it’s pointless fighting to bury them in the permafrost.

I visited Svalbardbutikken, the only supermarket, which was surprisingly well-stocked with fresh produce, wine, outdoor gear, and general goods. There were lots of outdoor clothing stores, and you could find polar bear souvenirs everywhere. I took pride in not buying one.

In the above map, “Haugen” refers to a residential upper‑valley neighbourhood. In Norwegian, haugen simply means “the hill” or “mound,” derived from Old Norse haugr.

I was told that there were no street names, with addresses given by area number and house number, and I didn’t see anyone carrying rifles (not required inside the town limits).

Most of the cars looked the “worse for wear” probably due to the cold and salt, and it was summer, so there were big parking areas for snowmobiles.

I was also told ownership was rare, and most people rent through their employer (e.g. mining company, university, government, tourism operator). Also rent is expensive compared to mainland Norway, and difficult to find, although heating and electricity are subsidised and centralised. One of the guides had been living there for six years, but said that there was no social life, and that there were no old people because there were no elderly care facilities.

In fact one of the guides said that healthcare services are deliberately limited on the island, and that there are no elderly care homes, hospices, or nursing facilities.

A good sign was that we were told to wait for “our” coach at 17:10, and it arrived exactly on time. The drive to the ship took around 15 minutes.

Unlike many traditional ports formed around natural bays, estuaries, or protective inlets, Longyearbyen’s harbour is more of a semi-exposed industrial shoreline along the southern edge of the bay Adventfjorden, a broad and relatively open fjord that feeds into the much larger Isfjorden. All docking is done via straight piers built out from the relatively flat gravel shoreline, not within carved-out or sheltered docks. The main cruise dock (Bykaia) was built on reclaimed land and is effectively a platform pinned into the fjord, reinforced for trucks and passengers, but has no shelter from above or around. The coal pier is bulkier and longer, reflecting its original purpose for handling heavy, slow-moving conveyor-belt coal operations. It lacks finesse but is more ruggedly built.

Ocean Explorer was moored on the coal pier, so just outside town and nearer the airport.

Boarding was fast. Handover passport, and pick up pre-prepared card for ID and as a room key.

Once aboard, the first thing I did was profit from my “free” balcony, only to find the Norsel alongside for bunkering. This is a 96 m, 2,490 ton gross, 22-year-old, Norwegian crude oil tanker.

It cast-off about 20 minutes later, and we were ready to sail. Or if you prefer a less romantic term, we “got underway”.

Broadly speaking, the cabin was perfect. It was comfortable, spacious, and more than enough for the “single” me. In a separate blog post I will try to compare this ship, this cabin, and this “explorer” trip with the Antarctic trip I took in late 2024.

For now I liked the overall impression of the cabin, I found many features perfect for my needs, e.g. good storage space, comfortable bed, good desk, seating, good sized wall safe, etc. The only real comment I would have is about the “universal” power sockets. There were only three, and the “classical” two pin plug you find on many simple appliances (e.g. laptop, shaver, etc.) often hung-loose and didn’t always connect to charge.

One key issue was that for some reason the full length “French windows” were difficult to open, and, despite being double glazed and very sturdily built, were freezing cold. I kept the heating on in the room at maximum all the time, in order to keep a comfortable 20-21°C.

The bathroom was spacious, very functional, but with just one defect. There was a socket only destined for electric shavers, and with my shaver it did not work.

In comparison with the cabin on my Ponant Antarctic cruise, this cabin appeared more spacious and better designed, although I’m not a fan of excessive fake wood. This bathroom was bigger and certainly more comfortable. The cabin on the Le Lyrial has a smaller bathroom with a slightly smaller shower, and a separate, but quite narrow WC.

18:00 We set sail to Smeerenburg.

As we sailed out, on the port side I could just see a few radomes, covering satellite dishes. This is just a small part of Svalbard Satellite Station (SvalSat) located on Platåberget (Plateau Mountain). In fact hidden from view there are over 100 antennas, making it one of the largest commercial ground stations globally. It high latitude in Svalbard allows contact with polar-orbiting satellites on every orbit, which is not possible from lower-latitude ground stations. The site provides real-time data downlink and telemetry, tracking, and command (TT&C) services, for Earth observation, weather monitoring, climate research, and scientific satellites (including the recent Sentinel satellites). All infrastructure is connected via a dedicated fibre-optic link to the mainland through the Svalbard Undersea Cable System, ensuring high-speed, low-latency data transmission. The link consists of two redundant submarine fibre-optic cables that run from Svalbard to Harstad on mainland Norway, via Andøya. It’s worth pointing out that due to Svalbard Treaty constraints, military uses are restricted, so the station is officially used for civilian purposes only, although dual-use data (e.g. weather, remote sensing) is possible.

Before a buffet dinner, there was a welcome and briefing in the Explorer Lounge on Deck 5, which included the programme for the next day. The programme was not printed and distributed, but was on the TV in each room, and placed near the lift.

On the Ponant Antarctic cruise the next-days programme was printed and placed in everyone’s cabin in the early evening. I understand the idea to avoid excessive paper, but I still have all those one-page programmes, as a keepsake. About three week after the cruise, passengers were sent a very substantial photo-video archive, with included all the daily programmes and even the daily menus in the dining room.

After the welcome and briefing followed an obligatory safety drill, including donning the lift-vest, and practicing the evacuation routine.

I won’t comment here on the meals, but it’s sufficient to say that they were a “good average”, but not better.

4 July 2025 (Day 2)

One source of useful information is the Norwegian Polar Institute’s Cruise Handbook for Svalbard.

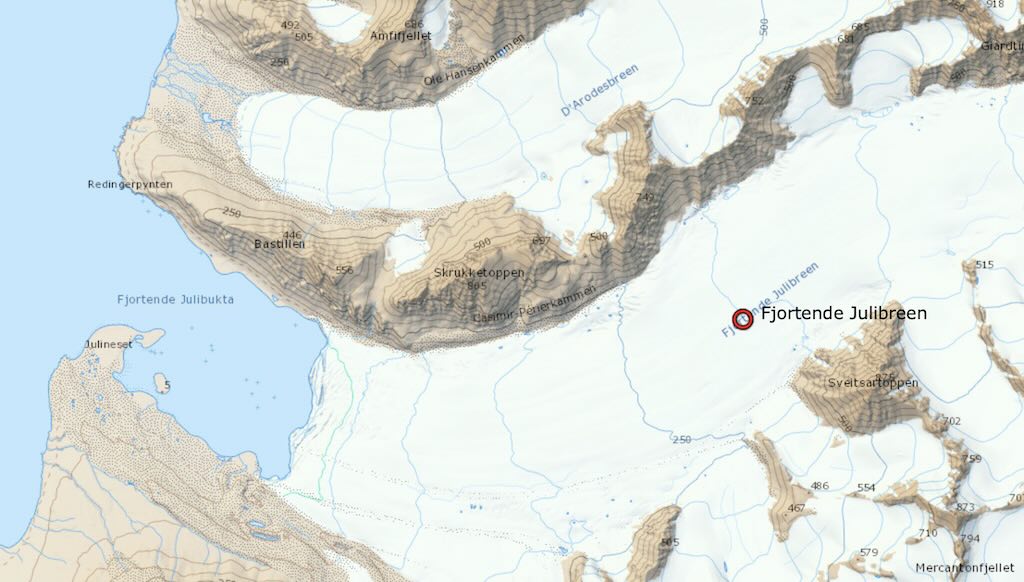

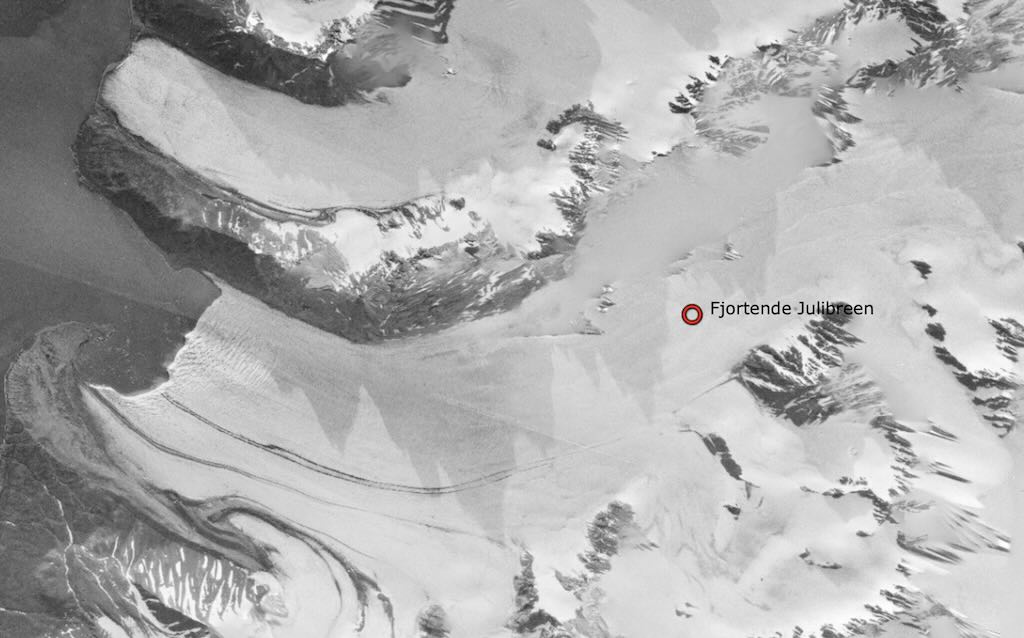

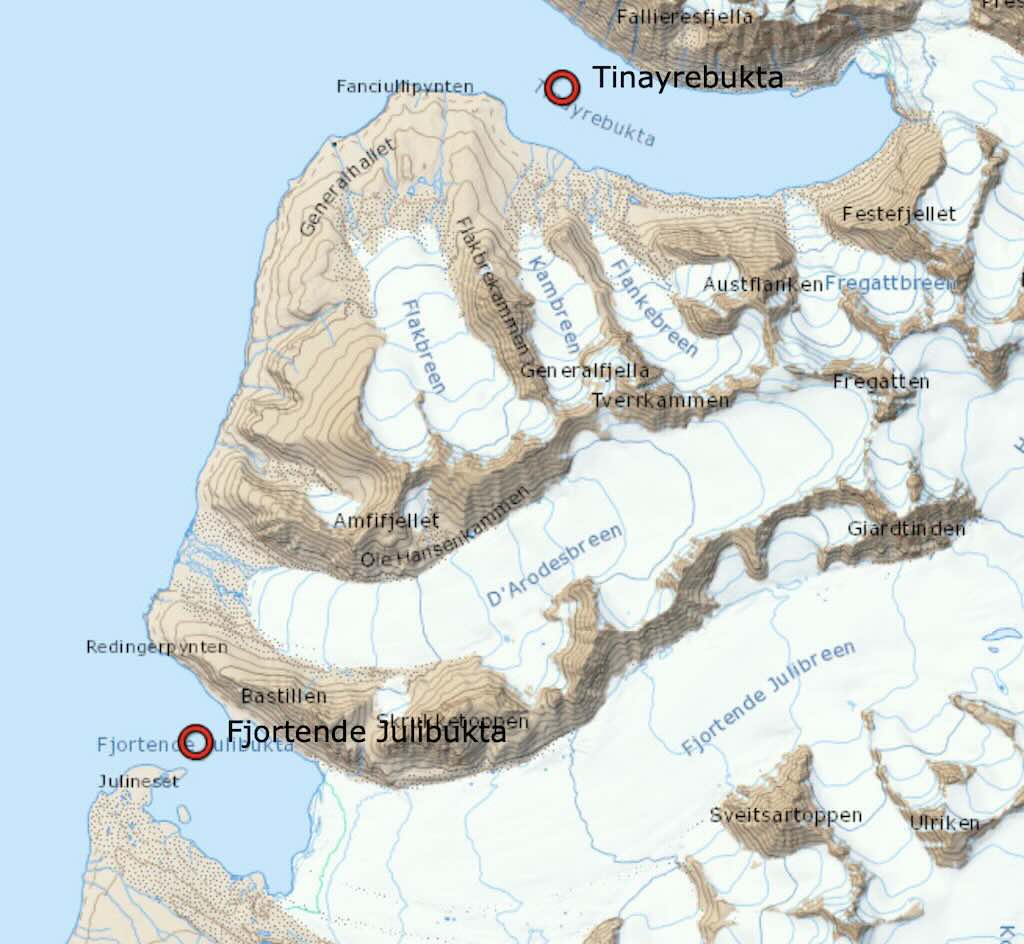

Most of the maps are taken from TopoSvalbard. And it’s important to grasp the ending of words, that can indicate a geographical feature. Here are some useful examples:-

-fjorden/-fjorden = Fjord (narrow sea inlet)

-fjellet/-fjella = mountain/mountain range (fjell = mountain, so -fjellet means the mountain, and -fjella means the mountains)

-neset = headland/point of land (from -nes a promontory)

-tinden = peak/summit (from tind = peak)

-breen = glacier (from bre = glacier)

-bekken = stream/brook (from bekk = stream)

-høgda/-høgdi = height/ridge (from høg = high, høgda = “the height”)

-luva = could describe a rounded hilltop or summit shaped like a hood

-hallet = the slope or “rock slab”

-vannet = lake

-vollen = meadow

-nakken(e) = the ridge(s)/neck(s) (from -nakk = ridge)

-vika = bay/inlet

Reminders:-

fjell = mountain, fjellet = the mountain, fjella = the mountains (plural definite)

bre → breen (the glacier)

tind → tinden (the peak)

nes → neset (the point/headland)

And as an example of a more complex meaning…

-tunga is often used to describe a tongue-shaped landform, so could be a narrow ridge, or peninsula or promontory, or glacier tongue (i.e. an extension of ice), or tongue-shaped mountain spur.

We had set sail yesterday (3 June) from Longyearbyen to Smeerenburg just before 18:00. The distance was between 100 to 110 nautical miles (nm), depending on the exact route taken, and the time taken was probably around 10 hours.

07:00 There were three options for breakfast on board. At 07:00 there was coffee/tea and pastries served in the Observation Lounge on the Deck 8. From 07:30 to 08:30 breakfast was served in both the Main Dining Room on Deck 5, and in the bistro on Deck 8.

My breakfast routine was simple. At 07:00 I would go for a bowl of musli/yogurt and a coffee in Observation Lounge, and at 07:30 I would continue with coffee (still taken from the excellent machine in the Observation Lounge) and some pastries in the bistro just next door on Deck 8.

In fact I would often get up early because on the observation deck (Deck 8) the team would be out checking the landing sites for wild animals. Remember that we were not allowed to land if there were wild animals on the landing site, e.g. polar bears, walruses, etc.

Meal options

Before moving on, it’s perhaps useful here to look at the meal options.

Breakfast options

There were three options for breakfast onboard. At 07:00 there was coffee/tea and pastries served in the Observation Lounge on the Deck 8 (see above). From 07:30 to 08:30 breakfast was served in both the Main Dining Room on Deck 5, and in the bistro on Deck 8 (see below).

In the Observation Lounge there was a proper coffee machine, and a small selection of breakfast options on the counter on the left.

I will take the opportunity to mention that in the library on Deck 6 there was also a proper coffee machine, and a constant supply of biscuits.

Both proper coffee machines worked 24/24. However, elsewhere coffee urns could be seen, but the coffee was occasionally terrible (and usually worse).

Breakfast in the bistro on Deck 8 was a very complete and reasonable buffet (excepting the terrible coffee). Staff and service were perfect.

Lunch and dinner options

These were either table service in the Main Dining Room on Deck 5 (see below), or self-service buffet in the bistro on Deck 8 (as seen above).

I twice tried the dinner menu service in the main Dining Room on Deck 5. I found the atmosphere “stuffy” and overly formal, the food options boring, and the food itself ordinary. Fortunately there was no formal dress code, and no captains dinner, but he did host a cocktail.

Otherwise I went to the bistro on Deck 8 for both a buffet lunch and buffet dinner. Sitting in the Main Dining Room the tendency is to eat too much, and so it’s simply nicer to be able to pick and choose. I will admit the buffet was not that much better, but there was usually something that was well prepared (e.g. the grilled tuna was excellent), and the cook enjoyed adding a bit more Tabasco and spices which I appreciated “muchly”. Also I could then just stroll from the bistro to the Observation Lounge and get a decent coffee.

Point of comparison with my Antarctic Ponant cruise, was that passengers on Quark appeared to focus less on the niceties of good cuisine, and I guess what was served amply met their expectations. The cuisine and the options on the Ponant cruise, were not exceptional, but were at least “two stars” above the options on Ocean Explorer. But not to worry, I had been warned.

And it’s worth mentioning that on the Ponant Le Lyrial full room service was included in the forfeit, as was Champagne at the bar. The Champagne certainly made “life at sea” more agreeable!

Snacks & drinks

Here and there, snacks and drinks were served. Before the evening de-briefing and planning meeting there were some drinks (I took the fruit juice) and some finger food. The hot options were usually delicious, but the canapés were less successful (see below comment).

Coming back from a zodiac cruise or land excursion, a selection of canapés and small sandwiches were usually served, along with a warm drink.

As a general comment on the canapés and sandwiches, they were quite poor, but edible, if hungry. A canapé consisted of one of two “things” plonked on a small square of thick-cut white bread, all held together with a toothpick. Sandwiches consisted of stuff plonked inside a little bread role having zero taste and undetermined nutritional value. Below is a photo of their best effort, which presented better than it tasted.

PS – Why stick a small plastic tree in the centre of a double-height window is beyond me. In particular when the explorer team was asking everyone to collect any plastics, etc. they saw during their walks.

Wines

I may “winge” a bit about the food, but I had been warned. However, no one warned me about the wines. The sparking white served in flutes was almost undrinkable. This is totally unacceptable, because there are excellent sparking wines available at very, very reasonable prices. I could say the same for the red wines, where the focus appeared to be on having a thick dark red colour in the glass, to the exclusion of any other criteria. I will admit I only tried three wine options, but then gave up. I should have tried the whites, but didn’t. The beer in the bistro was ok, but I usually drank orange juice.

09:00 Mandatory presentation of AECO briefing and Zodiac operations

Easiest way is to have a look at AECO guidelines, and in particular their Operational Guidelines and Small Boat Operational Guidelines.

I presume the initial intention was to land and visit “blubber town”, and see the most obvious remains, the large circles of blackened rubble that once served as the foundations of the blubber ovens.

The plan was changed because wildlife was visible on the shore. This was prioritised and we stayed on the zodiacs to observe polar bears and walruses.

For completeness it’s worth mentioning that during the 17th century, the Smeerenburg settlement was a thriving whaling outpost. Dutch and Danish whalers sailed the icy northern waters in search of blubber, which they would render in the Smeerenburg ovens.

In the early 1600s, Dutch and Danish whalers came to the waters around the Svalbard archipelago, whose most profitable whaling grounds centred on the island of Spitsbergen. In 1619, the whalers founded the settlement of Smeerenburg, literally meaning “Blubber Town”, on Amsterdam Island (Amsterdaøya) in northwest Svalbard. The location was chosen because it was near bowhead whale feeding grounds, with sheltered waters and beaches suitable for pulling carcasses ashore. Tales of the “booming” Smeerenburg were highly exaggerated with claims of hundreds of ships and as many as 18,000 men visiting the settlement during the short summer seasons.

In reality, as later archaeological evidence showed, Smeerenburg was likely visited by perhaps 400 men and 15 ships during its peak seasons (it was a seasonal camp), and had around 19 buildings during its heyday in the 1630s. Still, it was an important outpost for processing the valuable blubber, which at the time required a local land-based operation.

The blubber was rendered in vast copper vats placed on top of blubber ovens, whose circular foundations were made from bricks and “blubber cement”. This cement was made using a mixture of whale oil, sand, and gravel, which formed a solid base not unlike asphalt.

Smeerenburg was a short-lived settlement. It was already in decline by the mid-1640s, as whale numbers dropped drastically and the processing of blubber into oil was more frequently done onboard. After 1645, pelagic whaling (open sea/offshore rather than shore-based) became dominant. The outpost was eventually abandoned around 1660 and was stripped of any useful materials.

On the shore we saw three polar bears (a mother and her two young male adults) and about 10 walruses. The photos above are of one of the young males enjoying a walrus. It’s important to remember that cubs stay with their mothers for about 2½ years, during which time the mother provides all the food. This male cub is certainly nearing maturity, and after separation, young males typically become independent and competitive, not cooperative. Polar bears are solitary by nature, especially once they leave their mothers, and are especially intolerant of competition, so food sharing is rare.

Walruses haul-out in large, tightly packed groups on beaches primarily due to a combination of biological necessity, social behaviour, and environmental conditions. Firstly, walruses have a thick blubber layer for insulation in cold water, but on land, this same fat can cause overheating. By lying still and letting the air cool them, they avoid expending energy. What looks like “sunbathing” is just letting the cool air (not the sun) regulate body temperature. Blood vessels in their skin dilate, especially on flippers, to dump heat. So they’re not taking the sun for warmth, like reptiles, but cooling down in a relaxed state. Secondly, lining up close together creates a protective mass, reduces the risk of predation (e.g. from polar bears). In fact young calves are kept in the centre, shielded by larger adults. Thirdly, after diving and feeding (often for clams and mollusks on the seafloor), walruses need long periods of rest. Their metabolic recovery takes time, and they lie motionless to digest food and rebuild oxygen stores.

The key parameter is “viewing distance“, and 500 metres is now the preferred minimum distance on many expeditions. Initially AECO published a minimum of 300 metres, but many operators now enforce 500 metres, especially with increasing safety concerns and polar bear unpredictability. Although I was told that onboard our viewing distance was about 300 metres, and the main objective was to not disturb the animal life.

In addition under Norwegian Svalbard law, it is illegal to seek out or disturb polar bears. If a bear is within visible range, landings must be cancelled.

Those people with powerful zoom lenses and/or good quality binoculars could see that one of the young male polar bears was enjoying tearing apart its dead walrus. This was in fact hard work. The polar bear was looking for the blubber, but had to get through 10-15 cm of hard skin.

The viewing distance for walruses of 300 metres is often enforced near haul-out sites. AECO guidelines formerly allowed 30–50 metres, but these are increasingly seen as minimums only in exceptional conditions (e.g. from small boats, in silent drift).

What we could see was about 10 walruses laying on the beach. Also at times we could see one (or more) walruses swimming. Admittedly, it’s very difficult to identify the number of individuals in a haul-out when visually it looks like just a chaotic pile of animals heaped next to each other.

After the visit to Smeerenburg, we immediately set sail to Alicehamna, a picturesque bay located on the eastern side of Raudfjorden. It usually features calm waters ideal for anchoring and landing small boats. The distance was about 20-25 nautical miles depending upon the exact route taken (between 2-3 hours).

The name Raudfjorden means “Red Fjord” thanks to reddish sandstone in the hills. The place is named after Princess Alice, the vessel of Prince Albert I of Monaco, who explored Svalbard between 1898 and 1907. Of course, he named his ship after his second wife, Marie Alice Heine. She was on her third marriage, after marrying a decedent of Cardinal Richelieu, and then marrying a descendent of Cardinal Mazarin. The fact that she was born in the French Quarter of New Orleans may explain her penchant for French nobility.

This was a landing with the zodiacs. It was important to keep everyone in groups, since polar bears had been regularly seen in the region. What this meant was that there were several stops, with a member of the explorer team giving a small presentation. And at each stop and along the route the explorer team were stationed and armed.

The role of protecting explorer tourists in Svalbard, especially in polar bear territory, is highly regulated due to the dangerous environment and strict Norwegian laws. Guides and expedition leaders must meet several legal, training, and equipment requirements.

All tourism activities in Svalbard must comply with Svalbard Environmental Protection Act, the Governor of Svalbard’s regulations, and Norwegian Firearms Law (for bear deterrence), which have been customised for application in Svalbard.

Commercial operators and guides must notify the Governor of Svalbard in advance of trips outside the settlements, especially into designated polar bear habitats. Anyone leading tourists in non-urban areas (e.g. expeditions, photography tours, hiking, kayaking) must be capable of defending the group against polar bears.

This means that guides must carry the following deterrents and firearms when outside settlements:-

- .308 Winchester, .30-06 Springfield, or larger, bolt-action rifles, but semi-automatics are forbidden.

- Signal pistol or flare gun to scaring off polar bears from a distance.

- Tripwire systems for overnight camps. These surround tents and trigger noise/explosives to deter bears.

- Binoculars.

- Bear deterrent spray (optional, but allowed).

- Satellite phone / GPS beacon, for remote expeditions.

It’s worth stressing that a powerful cartridge is needed that can penetrate thick muscle and bone. Both .308 Win and .30-06 are capable of stopping a charging bear with proper shot placement and the right type of ammunition (typically heavy, controlled-expansion bullets). They do not need to be chambered (round in the barrel) at all times, but a loaded magazine (ammunition in the magazine) is expected.

Commercial guides or group leaders must have documented firearms training, and must prove safe handling and marksmanship. This can include range practice in Norway. They must also have polar bear awareness training conducted by the Governor’s Office or approved bodies. They must also be trained in First Aid and survival in remote/wilderness areas, including Arctic terrain, and have practical knowledge about sea ice, glaciers, and weather. Annual revalidation is recommended.

Lastly, polar bears are protected by law, and killing a polar bear without just cause may lead to criminal charges. Later we learned (not validated) that a person could be prosecuted for needlessly killing a polar bear. To ensure that a need was clearly seen, the shot must be to the bear’s face and must be made at a distance of less than 50 metres. A shot to the head or body, and made at more than 50 metres, might suggest that killing the polar bear, was not a matter of life-or-death. It’s worth mentioning that a polar bear can run up to 40 km/hr, so they can cover 50 metres in about 5 seconds. In the last 20 years only two people have been killed by polar bears. Approximately 3 polar bears are killed each year by people acting in self-defence. Over the past 20 years, only one involved formal charges, and it ended without prosecution.

The first stop on the shore, was a cabin called Raudfjordhytta. It was originally a Swedish trapper Sven “Stockholms‑Sven” Olsson’s secondary base (built 1927–28), now maintained as an emergency shelter.

The story goes that he was born in Stockholm in 1884, but moved to Longyearbyen in 1916. He began working as a steward at Camp Morton (a coal mining encampment) before switching to trapping in 1922. It’s during this period that he earned his nickname “Stockholms‑Sven”. In 1927–28, he built a secondary trapper’s hut at Alicehamna, Raudfjordhytta, as well as another hut at Biscayarhuken. It’s worth remembering that all structural wood, e.g. framing, planks, internal boards, etc., had to be transported by ship from Norway or elsewhere, the island itself offering no wood.

However, a severe facial injury from a mine avalanche during his first winter transformed his life. Afterwards, he became intensely reclusive and “he did not wish to show himself to people south of Longyearbyen”. Sven worked mostly alone, trapping in remote northern parts of Spitsbergen, ranging from Raudfjorden to Velkomstpynten. His solitary lifestyle and dramatic withdrawal from social life earned him legendary status among Arctic trappers. He symbolises the lone trapper archetype, i.e. resilient, independent, and profoundly connected to the wild.

The next stop walking up Brucevarden hill, was at the grave of a whaler, and further up there was the memorial of skipper Erik Zakariassen Mattilas, who died of scurvy in 1907–08. His grave, marked with a cross and cairn, is visible from Brucevarden hill.

The grave of the unidentified whaler is encased in stones with a wooden coffin inside, the burial is partially exposed, and its solid boards and even a skull are visible. It is now exposed because of frost heave and permafrost dynamics. Permafrost can keep organic materials frozen and intact, protecting the wood, bones, and sometimes textiles for centuries. In other Svalbard whaling cemeteries grave goods such as pine coffins, woollen blankets, and even moss from the whalers’ homeland have survived because of long-term freezing. What has happened is that rising Arctic temperatures have deepened the seasonal “active layer” and thawed the ground. Permafrost once tightly holding graves is now softening and collapsing. What this means is that coffins and remains are now being pushed upward or revealed as the soil sinks or shifts, sometimes directly exposing bones to weathering. Sites in Smeerenburgfjorden contain around 600 whaler graves, and academics are trying to document and study remains before they deteriorate beyond recovery. Analysis of remains and burial artefacts reveals social class, health (scurvy was common), genders, origins, etc.

The memorial to Mattilas is a simple wooden cross and a stone cairn, located near the summit of Brucevarden, just uphill from Raudfjordhytta.

Scurvy posed a deadly and immediate threat to those who wintered in extreme isolation, far from any possibility of fresh supplies, relying almost entirely on preserved foods, e.g. salted meats, dried biscuits, and little to no access to vitamin C, whose importance was still not fully understood. At that latitude, with total darkness for months and no vegetation, the absence of fresh food was absolute. Unlike naval expeditions, which by that time often carried lemon or lime juice, smaller land sites lacked such provisions, either through oversight or skepticism about their necessity. The extreme cold compounded the physical toll, weakening the immune system and accelerating the impact of vitamin deficiency. By late winter or early spring, as stores ran low and bodies became depleted, scurvy set in. Gums would bleed, joint became painful, fatigue set in, and eventually organs failed. Mattilas, like others in similar Arctic graves, likely suffered a slow and painful decline, his body unable to maintain itself without the vital nutrients fresh food provides.

Scurvy did kill many earlier Arctic mariners and whalers, though precise numbers aren’t recorded, archaeological findings confirm it was a common cause of death. However, it has now been determined that lead poisoning, likely from solder in canned food, was often confused with scurvy.

In between there was another stop, and a presentation on the local geography/geology, with particular reference to what we were walking on, namely a moraine. In fact the ground beneath our boots was angular and loose, a jumble of shattered rocks of varying sizes, some grey-green phyllites (a type of foliated metamorphic rock) and quartzitic sandstones, remnants of Svalbard’s oldest bedrock. The rusty brown streaks in some rocks are where iron-bearing minerals have oxidised, giving the stones a weathered, almost bruised look. Boulder-sized stones are scattered irregularly, dumped here by glacier ice that once swept across Raudfjorden and then receded. Also the permafrost just beneath the surface makes the soil thin and frozen, so there’s no real vegetation. Looking around you can see some steep, angular ridges carved by glacial erosion. Then there are the flatter valleys that once contained glaciers, some still do. These date back to Caledonian orogeny (roughly 490–390 million years ago). The current landscape has been formed over hundreds of millions of years, and rearranged more recently by ice. The nearby summits are fractured and sharp-edged, often with frost-shattered rock fields (blockfields) near their crests, where freeze-thaw cycles have broken stone into gravel-like debris.

18:15 Captain’s Welcome Cocktail

19:00 Welcome Dinner

21:00 After dinner there was a debriefing, and an outline of tomorrow’s visits.

I’m not sure what I should make of this day.

Positives were that it was very well organised. Given the potential danger from polar bears, being well organised is important. The talks during the landing, and in the de-briefing were excellent. The expedition crew were well prepared, and enjoyed presenting “their” subject. Another sign of the professionalism and good organisation, was that walking sticks were on the beach for the taking.

Negatives were (for me) the over enthusiasm in seeing polars bears and walruses at 300 metres. I didn’t have a camera with a powerful telephoto lens nor a top-end pair of binoculars, so these polars bears were just white “blobs” on the horizon. The photos shown here were taken by one of the explorer team, with professional equipment.

I also found it odd that despite the company being American based and many of the passengers American, nothing was celebrated, or even mentioned, about the US 4 July Independence Day.

The above photo is of one of the team of expert guides. She was a nice woman, and as we can see, always smiling. But if you look carefully you will see the rifle, and possibly the orange flare gun, and they also usually carried a knife. These were precautions against polar bears. Walking routes were watched over, and groups were accompanied. This was a formal obligation, as was having people who were trained to use guns if needed. It was often mentioned that no one wanted to have to kill a polar bear, so it was important to respect the rules and stay together.

Point of comparison with my Antarctic Ponant cruise, the Quark explorer team of guides and experts, were collectively better than the team I saw in the Antarctic. Many were more knowledgeable, and most presented better, and they all transmitted a passion for their subjects. This is not a criticism of the team on the Ponant cruise, it’s just a point of comparison, between very good and excellent.

Another point of comparison was that the Quark team were much more accessible. In the bistro I almost always found myself sharing a table with one or other of the explorer team, and chatting not just about the cruise, but about life in general.

5 July 2025 (Day 3)

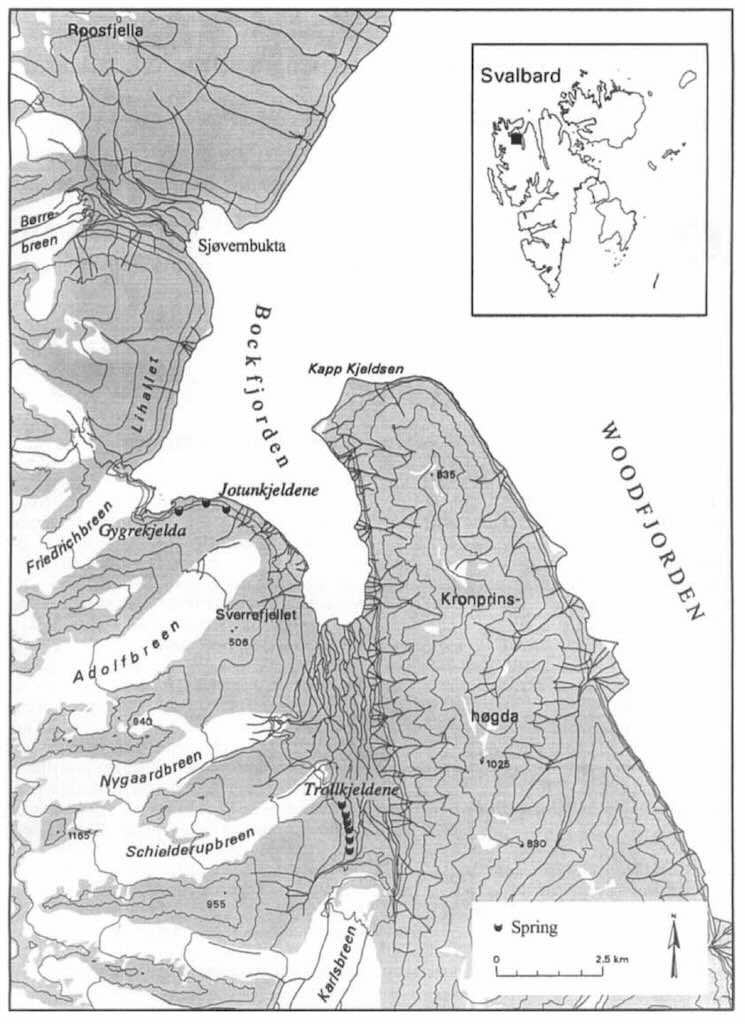

During the night we sailed to Jotunkjeldene, in the Bockfjorden. The distance was probably ~30–35 nm, taking 3-4 hours.

09:00 Jotunkjeldene in Bockfjorden (zodiac landing/walk)

Jotunkjeldene are geothermal springs located in Bockfjorden, on the northwest coast of Spitsbergen. The name Jotunkjeldene translates from Norwegian as “the giant’s springs”, referencing Norse mythology (Jotun = giant), and Bockfjorden is named after Arctic explorer Franz-Karl von Bock.

Hot springs, is a slight exaggeration, since the springs are typically around 20°C, but any form of hot spring is highly unusual in the High Arctic.

I didn’t see the two springs, I think in part because there were warnings to avoid walking on fragile carbonate terraces. Different groups set out on various hikes, but I stayed with a group that looked more at the tundra vegetation, etc.

This was an opportunity to look at what we were walking on, and to focus on the difference between permafrost and tundra.

Permafrost and tundra are distinct but interconnected components of cold-region ecosystems (polar or alpine), each with unique characteristics that shape the distribution and survival of plant and animal life. While they often occur in the same general environments such as the Arctic and sub-Arctic, their roles within those systems differ in subtle but crucial ways.

Permafrost is a geocryological condition, which means ground (soil, rock, or sediment) that remains at or below 0°C for at least two consecutive years. While tundra is a climatic biome, defined by low temperatures, short growing seasons, and the absence of trees. These systems often overlap, but they are not synonymous. The presence or absence of permafrost fundamentally alters how tundra ecosystems function, particularly in terms of soil structure, water dynamics, and biological productivity.

In regions like Smeerenburg, permafrost is continuous and thick, reaching depths of hundreds of meters. Only a shallow active layer, typically no more than 20 cm deep, thaws during the brief Arctic summer (the temperature at the top of the permafrost is often well below –2 °C, limiting summer thaw penetration). This thin, seasonally thawed layer is where all plant and soil life must operate. Because water cannot drain into the frozen substrate, soils become waterlogged in summer, creating cold, anaerobic conditions that limit nutrient availability and root penetration. Vegetation is correspondingly sparse and patchy, dominated by mosses, liverworts, crustose and fruticose lichens, a few grasses and sedges, and very occasionally dwarf shrubs like Salix polaris. The plant community is slow-growing, low in biomass, and highly sensitive to disturbance.

Despite the seemingly barren conditions, the terrestrial ecosystem is animated by a remarkable, if cryptic, community of cold-adapted invertebrates. Springtails (Collembola) and mites (Acari) dominate the soil fauna, feeding on decaying organic matter, fungal hyphae, and microorganisms. They are essential to nutrient cycling in the thin organic soils. Dipterans, especially chironomid midges and fungus gnats, thrive in meltwater ponds and saturated moss beds during summer. These, along with rare beetles, spiders (notably Pardosa glacialis), and parasitic wasps, can make up a surprisingly intricate food web. Importantly, no rodents inhabit Svalbard, the archipelago lacks the soil depth and vegetative productivity to support them. Even Svalbard reindeer, a highly cold-adapted subspecies, are scarce or absent from Smeerenburg due to its limited vegetation and extreme exposure.

The consequence is an ecosystem where invertebrates play an outsized role in ecological processes. They form a crucial link between sparse plant life and larger predators, such as the Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus), which also scavenges marine-derived resources like bird eggs, carcasses, and intertidal matter. The proximity of rich seabird colonies enhances nutrient input into the terrestrial system through guano, enriching certain microhabitats and supporting bursts of biological activity during the summer thaw.

In contrast, Jotunkjeldene in Bockfjorden is Arctic tundra within a polar permafrost zone. Here, the tundra biome is shaped primarily by the high Arctic latitude and geothermal activity, rather than elevation. The permafrost is continuous in this region, though localised geothermal heating around the hot springs may create patches of increased thaw depth. As a result, plant life is still sparse and low-growing, though potentially slightly more diverse near warm ground areas, with mosses, liverworts, crustose lichens, and scattered dwarf species such as Salix polaris and Dryas octopetala forming patchy ground cover rather than continuous mats across the landscape. While still harsh and nutrient-poor, this environment supports a few herbivores such as Svalbard reindeer and Svalbard rock ptarmigan, as well as their predators, primarily Arctic foxes. Svalbard lacks rodents and has few avian predators inland.

The ecological difference between Smeerenburg and Jotunkjeldene is therefore not merely one of temperature or latitude, but one of ground condition and soil dynamics. Permafrost in Smeerenburg imposes a hard limit on biological activity by constraining root development, water flow, and decomposition rates. This results in a low-productivity system reliant on microhabitat specialisation and marine nutrient subsidies. By contrast, the tundra at Jotunkjeldene, although still underlain by permafrost, may show localised microhabitat variation due to geothermal heat, and thus supports slightly enhanced vegetation and seasonal biological activity near warm patches, but not the layered complexity seen in permafrost-free systems.

We can think of the tundra as the living room of life in the Arctic. And below we will see two quite different aspects of that life on the tundra. Firstly, some wild flowers.

Here we some white flowers with yellow centres, often with 8 petals, and called dryas octopetala (commonly known as mountain avens). This is a dominant pioneer species in alpine and arctic ecosystems. It helps stabilise soil and is one of the first to colonise post-glacial ground.

This is even more attractive as it is scatter across the tundra. It has bright pink to purplish five-petal flowers sitting on a cushion-like mound of small green leaves. It is silene acaulis (commonly known as moss campion). This is a textbook example of a cushion plant, which conserves heat and moisture in harsh environments. It is one of the most iconic flowering plants of arctic-alpine tundra.

Field Note: Reindeer Carcass at Jotunkjeldene

Location: Tundra near the geothermal springs at Jotunkjeldene, northern Spitsbergen

Date: 5 July 2025

Find: Partial reindeer skeleton (skull with antlers and cervical spine intact), with hair concentrated in ~2–3 m area, and bones (legs, ribs) dispersed over 5–10 m radius

- The skull and antlers were still connected to the cervical spine, indicating the animal likely died before shedding antlers, which male reindeer typically do between late October and December.

- Hair was still attached to the skull, and loose white fur was heavily concentrated in a 2–3 m zone, suggesting the body decomposed in place.

- Other bones (legs, ribs) were scattered over a broader area (5–10 m), most likely by scavengers such as Arctic foxes and ravens, which are known to be present on Svalbard.

- The animal’s teeth were worn nearly flat, implying advanced age.

Species: Svalbard reindeer (Rangifer tarandus platyrhynchus), a small, short-legged subspecies endemic to the high Arctic archipelago. Both males and females grow antlers, but on different cycles. Males grow antlers in spring, use them for rutting (mating), and shed them in late autumn. Females grow antlers in summer and retain them through winter into the next spring, helping pregnant females access limited winter forage.

Deduction: The presence of large, multi-branched antlers and their connection to the skull strongly suggest this was a mature male. The timing of antler retention implies he died before shedding, likely late autumn to early winter. The worn-down teeth indicate advanced age, possibly 8–10 years, which is old for a wild male reindeer in Svalbard, where winter starvation is a common cause of death. There were no signs of violent trauma or large predator activity. The most plausible cause is starvation, perhaps due to an icing event (i.e. when rain-on-snow freezes forage under ice), a well-documented killer of reindeer in Svalbard. His old age and likely weakened condition after the rut would have made survival difficult once snow and ice sealed over the tundra.

The bones scattered in a 5–10 m area suggest Arctic foxes dragged limbs away from the main carcass. Birds may also have fed on soft tissue early on. The fact that the skull, antlers, and spine remained mostly intact supports a natural death and scavenging scenario, not violent predation.

We were standing near the antlers and skull, and with the sea and ship behind us, we look inland. We see what looks like a conical volcanic peak called Sverrefjellet, which in fact is the heart of the Jotunkjeldene system, the landform responsible for both the spring system and the broader volcanic and glacial landscape around us.

The springs consist of large, terraced carbonate deposits, formed by minerals dissolved in the warm water on its way up through the bedrock. The water in the springs is groundwater that has been heated up so that the temperature at the surface is around 20°C all year. This can be linked to previous volcanic activity along a fault in the bedrock. There are two springs from which warm water emerges and runs down. I think we were near the western formation, where there is no longer a spring at the top. Rather, a spring emerges in the middle of the slope. The below map might help. We can see three springs indicated, and I think we are standing on the middle one looking towards Sverrefjellet.

Two warm springs, named Jotunkjeldene, about 2 km north of Sverrefjellet, were first discovered in 1910. Their location near to the Quaternary volcano, Sverrefjellet, clearly indicates a volcanic origin. A third spring was discovered in 1995 about 1 km west of the westernmost spring of Jotunkjeldene (where we were standing).

In addition there are another six springs, named Trollkjeldene, located about 5km south of Sverrefjellet. It’s reported that the southernmost of these springs was the warmest with a temperature of 28.3°C.

The history of this landscape began far before any volcano appeared. First came deep rocks, rivers, shallow seas, and tectonic chaos. The Caledonian Orogeny (Silurian–Devonian period~420–390 Ma) was a giant continental collisions creating a deep metamorphic basement (now buried), creating gneisses and schists. The first is metamorphic rock. It is formed by high-temperature and high-pressure metamorphic processes acting on formations composed of igneous or sedimentary rocks formed under pressures and temperatures over 300°C. The second is a medium-grained metamorphic rock generally derived from fine-grained sedimentary rock, like shale, typically forms during regional metamorphism accompanying the process of mountain building (orogeny).

This mountain-building cycle is seen throughout the northern parts of the British Isles, the Scandinavian Caledonides, Svalbard, eastern Greenland and parts of north-central Europe.

Then came sedimentary deposits (Devonian–Carboniferous ~390–300 Ma). This is identified by thick red and grey sediments (sandstone, siltstone) laid down in river valleys and shallow seas. These formed the fjord cliffs we see across Bockfjorden.

During the Mesozoic–Early Cenozoic (~250–50 Ma) Svalbard drifted away from Greenland. Old rocks cracked, and the fractures would later feed the volcanos.

Today none of this is visible in my photos, but all of it lies beneath my feet.

Then a volcano erupted here in the Late Ice Age, just before the last glaciers covered it. Sverrefjellet was a monogenetic (single-eruption) volcano, that occurred ~100,000 years ago (Late Pleistocene). It was possibly a few hundred meters taller than it is today, with steeper slopes. Its shape has been eroded but is still conical, although flattened slightly by ice and frost. It blew there simply because it followed fault lines that had been waiting for magma for millions of years.

After it erupted, ice and time erode the cone (~80,000–12,000 years ago). In fact the entire area, including Sverrefjellet, was buried under a thick ice cap (~21,000 years ago). The ice then scraped the flanks of the volcano, removed loose ash and rock, flattened parts of the cone. Boulders were rolled down its slopes and on to the plain below. These are the erratics in the photos. This just means a glacially deposited rock different from the type of rock native to the area in which it rests. Sverrefjellet endured as a nunatak, a peak sticking out of the ice and re-exposed after the glacier receded.

Over the last 15,000 years the land rose as the weight of ice disappeared, forming raised beaches and lifting valleys (called isostatic rebound).

What we seen today is a landscape shaped by freeze–thaw weathering, not lava or ice.

I’ve pulled up again the “beach photo”, of the opposite (eastern) side of Bockfjorden from Jotunkjeldene. What we see rising above the far shore are not volcanic. This is Devonian red sandstones interbedded siltstones and shales (~419–299 million years ago). Possibly with some Carboniferous marine limestones. They are visible today thanks to glacial erosion. Ice has carved out the U-shaped fjord basin between us and those cliffs. When the glaciers retreated (~15,000–10,000 years ago), the steep walls were left behind. Stream gullies and snow melt channels now incise the slopes (visible as white streaks and vertical shadows). The cliffs were further shaped by periglacial weathering, and constant process of freeze–thaw cycles open cracks, and rocks fall down the slopes.

First we looked out to sea, and now to the right from the Jotunkjeldene beach area, we have steep, reddish cliffs rising dramatically from the far shore of Bockfjorden. This is the most geologically expressive image of the sedimentary record in the area, and is part of the Woodfjorden Group sedimentary system.

We see steep red to reddish-brown cliffs, with horizontal layers, vertical gullies and snow-filled crevices.

The red sandstone and siltstone originally were deposited in river channels and floodplains in a Devonian rift basin (~390–360 Ma). Whereas the darker interbeds are shales or fine siltstones which would have been quiet-water settings like floodplains or shallow lakes.

These layers were deposited horizontally in a continental rift system when Svalbard lay near the tropical zone. The presence of red coloration signals deposition in an oxidizing (continental, not marine) environment, consistent with floodplain settings under dry/warm conditions.

What we see today is after the region experienced multiple tectonic events. The area was faulted and gently tilted creating weakness, that were followed by streams and gullies.

Glacial sculpting (~21,000–10,000 years ago) carved Bockfjorden into a U-shaped valley. The nearly vertical cuts are due to ice plucking and abrasion. Then came periglacial erosion from meltwater and freeze–thaw cycles. Today, frost weathering dominates, with water gets into cracks, freezes, and breaks apart the rock, forming the loose talus at the base.

Just as we could see some nice example of local flowers, we could also see some interesting and unusual rocks sitting on the beach.

This is quite a sizeable rock (more than one metre across), but it’s not local to Sverrefjellet (not basalt) or sedimentary rock. It looks to be metamorphic slate/phyllite with quartz veins. It matches Caledonian metamorphic basement rocks exposed further inland. Judging only by the type of stone it might have come from the Atomfjella Complex (~10–15 km to the southeast), or more generally from the Bockfjorden basement highlands, exposed 5–10 km inland.

However, this is a large, angular boulder with preserved cleavage, indicating short to moderate glacial transport. It hasn’t been water-rounded, so it likely wasn’t moved far by meltwater after deposition. So probably during the Last Glacial Maximum, it was transported as debris within the ice that flowed from the interior of northwestern Spitsbergen down into Bockfjorden and Woodfjorden, and on towards the coast. Reconstructions of Pleistocene glacial flow in this region (e.g. Hjellebreen and glaciers from the Vestfonna ice cap) suggest ice advanced from south–southwest to north–northeast, aligning with a source inland from Jotunkjeldene. That makes a 5–20 km range geologically reasonable.

In simple terms it is very old rock that was first exploded, and then came down inside a glacier, and was finally dumped on the beach, where it will remain until it is finally broken up by weathering.

The above massive rock (more than 2 metres across) was completely different from one analysed above, yet they were almost next to each other. This rock is identified as a strongly banded gneiss with migmatitic texture. So a metamorphic rock formed by high-temperature and high-pressure metamorphic processes acting on formations composed of igneous or sedimentary rocks. Migmatite is a composite rock found in medium and high-grade metamorphic environments, commonly within Precambrian cratonic blocks. It consists of two or more constituents often layered repetitively. One layer is an older metamorphic rock that was reconstituted subsequently by partial melting (“paleosome”).