In early June 2025 I participated in a New Scientist/Kirker tour package called “The Science of Champagne“, which evidently took place in and around Reims.

During the tour we were accompanied by drinks expert, Jonathan Ray and the tour manager Graeme Coles.

Jonathan Ray is the drinks editor of The Spectator as well as a drinks columnist for The Field and Spear’s. He is also author of All About Wine, Bloodlines & Grapevines and Drink More Fizz!.

This post is the second in a two-part posting, and covers the Tuesday and Wednesday of the tour.

The introduction and the first day, Monday, of the tour, can be found here…

Champagne I – je goûte les étoiles!

And you can also check out:-

Hotel – Loisium Wine & Spa, Champagne

Hotel – Royal Champagne Hotel & Spa, Champillon

At the end of this post I’ve copied over some French terminology, often specific to Champagne.

Tuesday 10 June

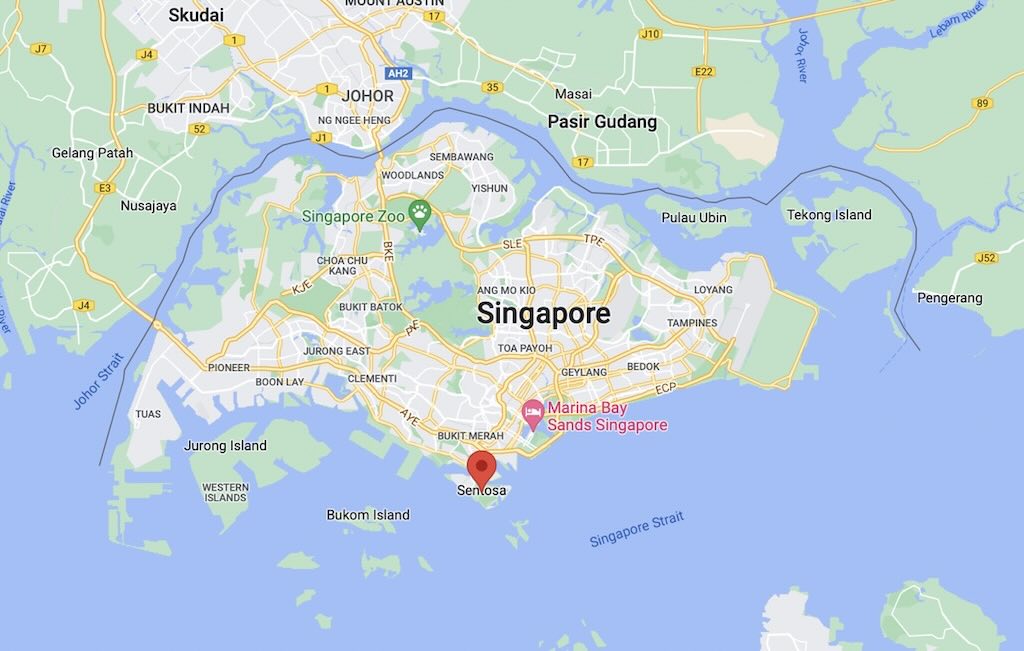

The day started with a drive to the historical heart of Champagne, the village of Aÿ. Destination Bollinger’s historic estate nestled among Premier and Grand Cru vineyards.

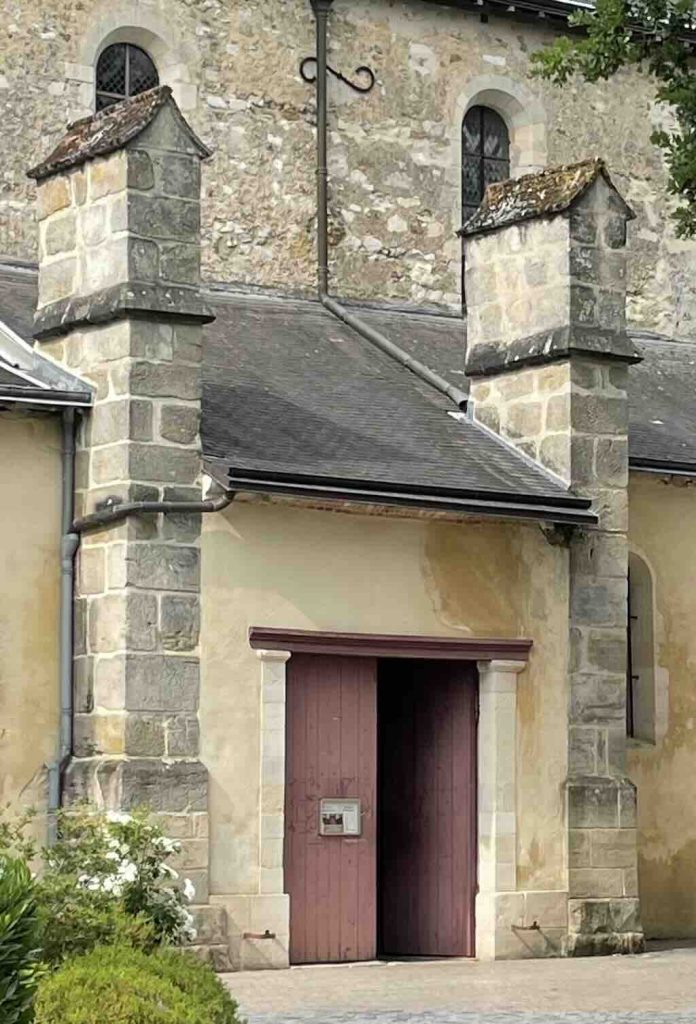

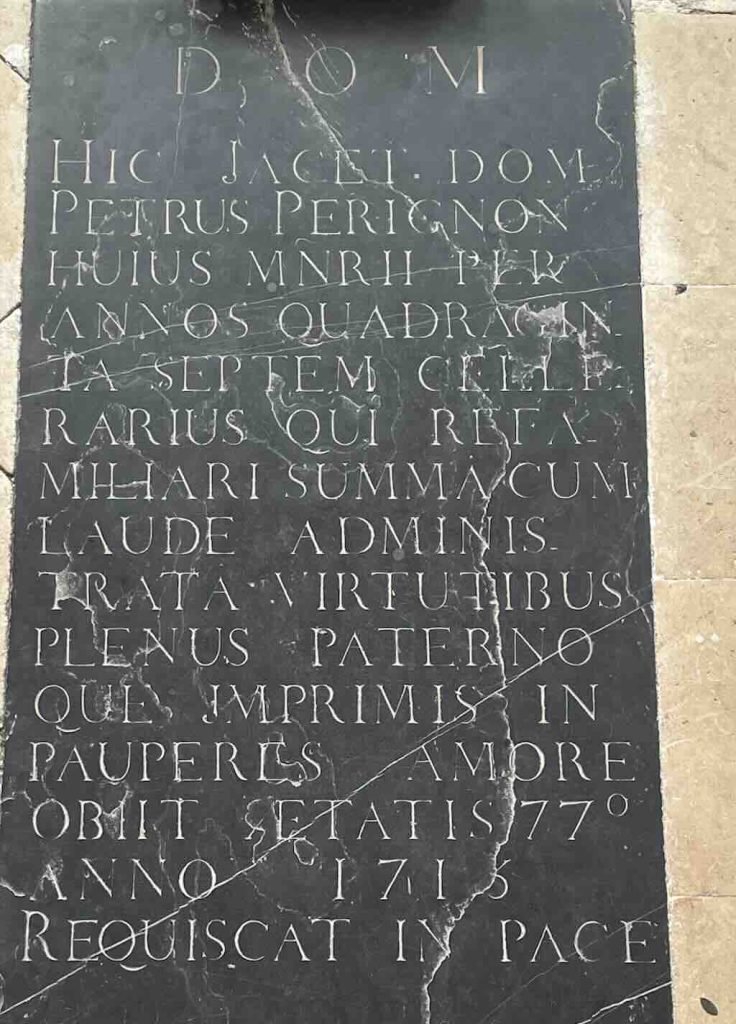

But on the way we made a slight detour to the Abbey of Saint‑Pierre in Hautvillers, and the tomb of the monk Dom Pierre Pérignon (1638–1715), known as Dom Pérignon. Popular myths frequently, but erroneously, credit him with the invention of sparkling Champagne, which did not become the dominant style of Champagne until the mid-19th century.

Initially the welcome at Bollinger felt more like a typical tourist presentation, but things warmed up as the visit progressed. So this time let’s start with the history of the house Bollinger.

Champagne Bollinger is one of the most prestigious and historically rich Champagne houses in France. It is known for its powerful, Pinot Noir-driven style and deep roots in tradition, family ownership, and terroir.

Founded in 1829 in Aÿ, in the heart of the Champagne region, the house began as a partnership between Hennequin de Villermont, Paul Renaudin, and Jacques Bollinger.

Athanase-Louis-Emmanuel Hennequin de Villermont (1763–1840), was a French naval officer who served in the American Revolutionary War. He was from a noble family with estates in the Champagne region. Later he would inherit land in Aÿ, which was already famous for its vineyards. The fact is that Athanase didn’t just lease out the land or remain passive, but actively co-founded the Champagne house. It’s perfectly possible that he saw winemaking as a way to preserve and elevate the value of his estate after the French Revolution, which had financially shaken many noble families.

What is sure is that he must have trusted Bollinger and Renaudin, and probably had an existing social or professional relationship with them. Athanase died in 1840, and Jacques Bollinger later married into the family, creating a dynastic continuity between the Bollingers and Villermonts. Due to noble conventions at the time, it was considered improper for aristocrats to engage directly in commercial enterprises under their own name. Thus, when he co-founded the Champagne house in 1829, it was named Renaudin-Bollinger, not “Villermont”, even though he was one of the key initiators.

Paul Renaudin came from a humble, local Champenois background. He was not an aristocrat or noble, like his founding partners. Renaudin was described simply as a “born-and-bred Champenois” and worked at Müller-Ruinart before co-founding Bollinger. It’s presumed that he was, or at least became, a skilled cellar manager. There’s no substantial record of Renaudin pursuing other ventures outside Bollinger, and he doesn’t seem to appear in later public accounts of the family. He died without descendants, but his name stayed on the company label until the 1960s.

Joseph Jacob Bollinger, known as Jacques Joseph Bollinger, was born in 1803 in Ellwangen (in the Kingdom of Württemberg). It’s probably that he came from a family that had connections to winemaking and commerce. Bollinger left his native Germany to train in the Champagne wine trade, and he first worked for the Muller-Ruinart house (and probably met Paul Renaudin there). His German heritage placed him among several key figures from the German states who shaped the early Champagne industry, e.g. Joseph Krug and Florens-Louis Heidsieck.

After co-founding the house with Paul Renaudin and Athanase de Villermont in 1829, Bollinger married de Villermont’s daughter, Louise-Charlotte, in 1837. Over time, the Bollinger family assumed full control, and the house has remained family-run for nearly two centuries. One of its most iconic figures was Lily Bollinger, who ran the house from 1941 to 1971 with both elegance and steely business acumen, helping to preserve its independence and global reputation.

Today, Bollinger is one of the few Grandes Marques still in family hands. The Bollinger family’s involvement continues through Société Jacques Bollinger (SJB), the holding company that oversees the brand’s interests.

It is interesting to be reminded of early winemaking practices, namely:-

- Wood‑fermentation & extended ageing – From the beginning, Bollinger embraced fermentation in oak barrels for high‑end cuvées, a practice now rare in Champagne today. This technique imparts additional structure, aromatic richness, along with subtle oxidative notes. Bollinger also ages their wines on the lees for well beyond the legal minimum, i.e. 3 years for the Special Cuvée, 5 years for the Grande Année, and more than 8 years for RD (Recently Disgorged) wines.

- Reserve wines in magnums since 1890 – Bollinger uniquely stores reserve wines in magnum bottles, some more than 15 years old, making them a key component in the Special Cuvée blend. This method enhances consistency and complexity in the non‑vintage.

- Preservation of historic techniques & cellar legacy – Bollinger maintains their own cooper in-house to care for oak barrels that can be more than 100 years old. In 2010, an abandoned cellar was discovered with bottles dating back to 1830. Bollinger preserved these using laser aphrometry to measure their pressure before disgorgement.

The aphrometer is a device used to monitor the final pressure inside the bottles and, indirectly, the quantity of carbon dioxide (or “bubbles”). Check out this article on the technique and more generally on the creation of the Bollinger Champagne “archive”.

The story of the Bollinger Champagne archive is interesting in itself. In 2010, an intern wandered into a dark extremity of the cellar complex and began moving a pile of empty bottles. Behind these, he discovered 600 bottles of old, forgotten Champagne, some dating back to 1830, as old as the Champagne house itself. The newest bottle dated to 1921. No Bollinger employee had any recollection of the storing of these special vintages, but they were possibly hidden out of sight from occupying Germans, or simply left and forgotten between the wars. The discovery of this remarkable treasure trove pushed the house to gather together all the old discarded and ignored bottles throughout the cellars, and to turn them into something useful, a liquid “archive” of Bollinger winemaking, with as many bottles as possible painstakingly analysed and restored. The result amounts to a collection around 5,000 bottles, an unparalleled archive of historic Champagne making.

Bollinger established its signature style through oak fermentation, long lees ageing, and reserve magnums. Lily Bollinger introduced innovations such as RD (Recently Disgorged) in 1967, and launched the prestige Vieilles Vignes Françaises from ungrafted old vines in 1969.

From 1971 onward, leadership passed through Bollinger nephews and cousins, namely Claude d’Hautefeuille, Christian Bizot, Ghislain de Montgolfier, and today Charles‑Armand de Belenet. The Bollinger family continues to hold majority ownership.

Today Bollinger owns an unusually high percentage of the vineyards it uses, over 180 hectares, of which more than 85% are classified as Grand Cru or Premier Cru. These holdings are concentrated in the Montagne de Reims and the Côte des Blancs, particularly around Aÿ, Bouzy, and Verzenay. The house’s vineyards provide it with a rare degree of autonomy and control over grape quality, setting it apart from many producers who depend on external growers.

Bollinger is also renowned for its commitment to Pinot Noir, which forms the backbone of its blends and contributes to the house’s signature structure and depth. The typical blend for its non-vintage Special Cuvée is around 60% Pinot Noir, 25% Chardonnay, and 15% Pinot Meunier. The house also produces single-vineyard, vintage, and prestige cuvées, e.g. La Grande Année and RD (Récemment Dégorgé), which emphasise maturity and extended lees ageing.

Today, Champagne Bollinger exports to more than 100 countries and maintains a strong presence in the UK, where it has long been associated with British cultural icons, most famously, James Bond.

Bollinger is also committed to environmental sustainability, having received the Haute Valeur Environmental (HVE) certification for its vineyards and investing in biodiversity and reduced chemical use.

The Maison Bollinger is the historic Champagne house located in Aÿ. Established in 1829, it comprises the production facilities (hidden to the left) and extensive cellars (through the central ground-floor door).

Our tour started with a visit to a small plot, just outside the site across the road. I think these were old, ungrafted Pinot Noir, and I suspect the plot was the 0.15 hectare Clos Chaudes‑Terres. Along with Clos Saint‑Jacques (0.2 hectares), the grapes are used for the Vieilles Vignes Françaises, a prestige cuvée.

It is said that the traditional method of planting is used, where the vines are planted in a tangle, not in neat rows. Also its mentioned that the vines are layered, i.e. where a cane from one vine is buried to produce a new plant, without grafting.

We saw neither of these features.

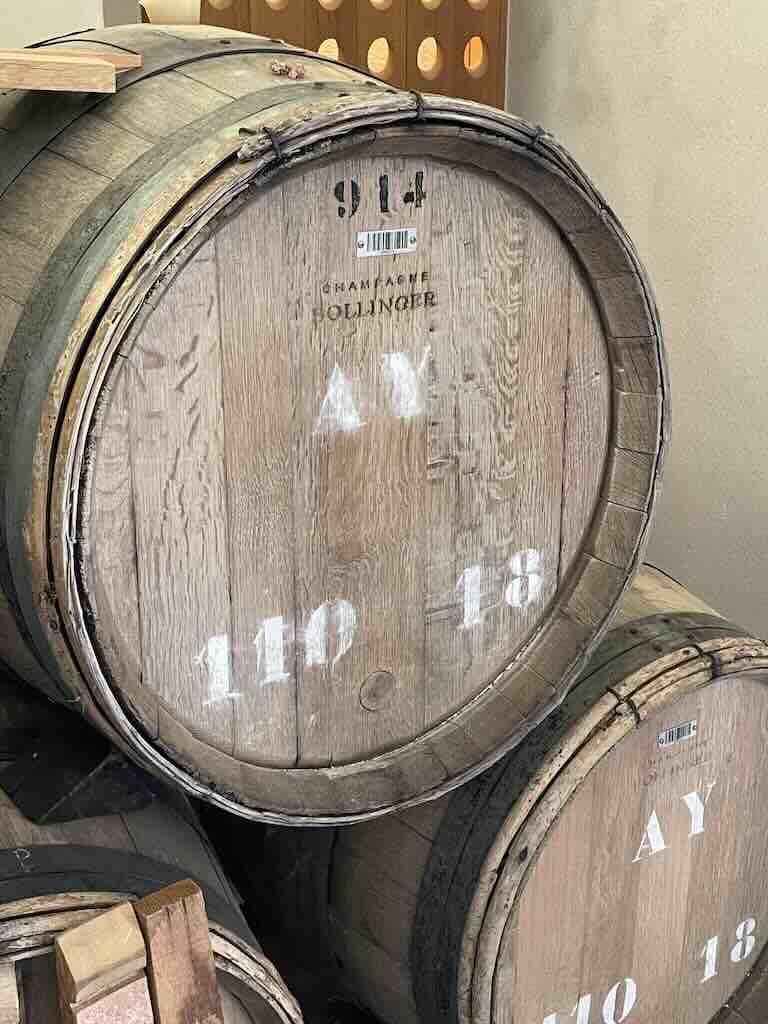

In the tour preplan we were supposed to see the barrel hall housing up to 4,000 oak barrels, many decades old, and meet the in‑house cooper. This didn’t happen, and instead we saw some old empty barrels at the entrance to the cellars.

It is my understanding that Bollinger exclusively uses around 4,000 second-hand oak barrels sourced from Burgundy, thus ensuring that the wood is fully seasoned and doesn’t introduce over-powering fresh oak aromas. Some of the barrels can be over 100 years old, and are maintained by Bollinger’s own in-house cooper, which is said to be the last full-time cooper in a Champagne house. I understand that the houses that employ oak barrels normally get them from one or other local “tonnellerie”.

As you might have guessed, new oak wood barrels are not “welcome”. Ageing or “seasoning” new oak barrels, whether for Champagne or other fine wines, is necessary, and is designed to soften the wood’s raw character, leach out aggressive tannins, and develop a more refined flavour profile.

Most of the “ageing” happens before the barrel is even assembled. Oak logs are split into staves, then left to air-dry outdoors for 24 to 36 months, sometimes even longer (up to 5 years for high-end barrels). This natural weathering leaches out harsh tannins, volatile compounds, and green wood flavours (e.g., bitterness, resin, and excess astringency). Rain, sun, and microbial action mellow the wood. It is possible to kiln-dry the wood, which is faster but produces less subtle results. Usually this ageing happens in the cooper’s drying yard, but if the wood comes from French forests, it may be seasoned near those forests.

The slight porosity of oak allows micro-oxygenation, which softens tannins, refines acidity, and enhances aromatic complexity. Bollinger considers the oak barrel part of its signature style. Each barrel plays a dual role. First it’s used to ferment fresh musts and later it houses reserve wines for their NV blends, such as Special Cuvée.

Every spring, casks undergo structural repairs (replacing staves or ribs), followed by cleaning, drying, and sulphuring to ensure ideal hygiene and fermentation conditions.

Each barrel is marked, and, as seen above, has a barcode. There is a house mark, a unique fût number, a vintage or year when the barrels was first used, village origin, volume, etc. and codes to track location/use history.

Hand-maintained casks reflect Bollinger’s craft-led ethos. You can see in the photo that the top and bottom’s more fragile edges (chimes) of the barrels are protected with flexible wooden bands that can easily be changed. Also part of barrel maintenance involves the light toasting (or re-toasting) of the interior of used barrels, and this often involves burning the dried lees (lies sèches).

During the tour we did see some of the 6 km of cellars and a few of the 12 million bottles stored there. And we did walk past the Bollinger’s “Galerie 1829”, their “secret” trove of rare historical vintages.

During our visit to the cellars, the guide was quite forthcoming in explaining the different winemaking processes and what made Bollinger different, etc.

Let’s just rapidly run through the winemaking process (focusing on Bollinger). Grapes are hand-harvested and within hours pressed to obtain the cuvée. The juice is separated by grape variety, vineyard parcel, and pressing cycle, and undergoes its first fermentation becoming still wine known as vin clair. Usually this is done in large temperature-controlled stainless steel vats, but Bollinger uses over 4,000 decade old oak barrels stacked in temperature-stable cellars. Each parcel is fermented separately, allowing the winemaker to judge its character (e.g. acidity, aroma, structure, clarity, etc.).

In early spring (March/April), the chef de cave and winemaking team perform the assemblage. Dozens or even hundreds of vin clair samples are tasted blind. For non-vintage Champagne, base wines from the current harvest are blended with reserve wines (older vintages stored in barrels or magnums). The goal is to create the house style, or reflect a vintage’s unique identity.

Once the blend is finalised, the still wine is cold-stabilised and filtered. Each bottle is filled with the final blend and a small dosage of liqueur de tirage, a mix of sugar and active yeast. This initiates the second fermentation in the bottle. The bottle is sealed with a crown cap and “bidule” (small plastic reservoir to catch sediment during riddling). Now the bottle is placed horizontally (sur latte) in the cellar, typically 10–12°C, humid, and dark. The yeast consumes the sugar, producing a small amount of alcohol, and some carbon dioxide (creating the bubbles).

The yeast eventually dies and forms sediment, called the lees. This is the sediment seen (above left) lying along the inside of the bottle. The wine is now maturing on its lees, a process called autolysis.

For non-vintage Champagne, the bottle will stay like that for a minimum 15 months (by law), but most top producers age 2–3 years. For vintage Champagne the minimum is 36 months, but most houses like Bollinger age for 8–15 years or more.

During this time, the lees break down, releasing mannoproteins and amino acids, which add creaminess, aromatic complexity, and finesse. The bottle remains undisturbed, lying on its side, slowly evolving. The sediment is a layer of the dead yeast. It is the physical trace of a transformation that gave the wine both its sparkle and taste.

After this aging, the bottle will be “riddled” (turned and tilted so the sediment slides into the neck). In the second photo above (on the right) we can see the bottles, neck down, on the wooden racks. And we can see that slowly the sediment is collecting in the “bidule” in the neck.

Then the bottle will be disgorged (sediment frozen and ejected), dosed (sweetness adjusted), corked, wired, and labeled.

The cellar visit culminated with a tasting. Frankly, I can remember the tasting but I can’t remember what we tasted. I presume it was a Special Cuvée NV, a Rosé NV, and I guess a vintage cuvée. I will admit that I found the wines of Chauvet more varied and distinct. Bollinger is not a Champagne I buy, but I was in fact looking forward to tasting that Pinot Noir (a grape I like very much). I think I left a little disappointed.

On the other hand I do remember the sparking discussion about Bollinger and James Bond. Along with detonating wristwatches and vanishing cars, there was always a glass of Champagne ready (properly chilled, of course). Through more than six decades of cinematic intrigue, Champagne flowed almost as freely as bullets, but as the idea of evening martini’s was buried, Bollinger emerged as the unmistakable signature of 007’s refined taste. Mind you, Bond does not déguste his Champagne in a white-wine glass, so we still have some work to do on the next James Bond.

In Ian Fleming’s novels Champagne was always essential to Bond’s persona, not just as a drink, but as a symbol of power, seduction, and class. He drank it in hotels, in trains, and during intimate meals (and more). In the books his early favourite was Taittinger Blanc de Blancs 1943 (in Casino Royale, 1953). But already he was far from faithful, since he also drank Krug, Veuve Clicquot, and occasionally Dom Pérignon.

In the films Bond regularly drank Dom Pérignon. In Dr. No (1962), Sean Connery scoffs, “I prefer the ’53 myself”. In Goldfinger (1964) it was “My dear girl, there are some things that just aren’t done — such as drinking Dom Pérignon ’53 above the temperature of 38°F”. So Dom was cool, exclusive, and always drunk by the Cold War elite.

However, Bollinger arrived in the 1973 Live and Let Die, with Roger Moore. But it was in Moonraker (1979) that things really changed. In a space-bound private jet, he says “Bollinger? If it’s ’69, you were expecting me”. Bollinger had arrived.

The story goes that Christian Bizot, then head of Bollinger, was friends with Albert “Cubby” Broccoli, the legendary Bond producer. There was no flashy commercial deal, no mass marketing push. Bollinger simply agreed to supply Champagne, and Bond agreed to drink it. There was no product placement fee, just cultural alignment. Since then, every official Bond film since Moonraker has featured Bollinger Champagne, often vintage, always seductive.

Bollinger has released several James Bond special editions:-

- Bollinger 007 Millésimé 2002 – released with Quantum of Solace (2008)

- Bollinger Spectre Limited Edition (2015) – a sleek black bottle in a gun barrel box

- Bollinger 007 2011 Vintage – paired with No Time to Die (2021), in a black and gold livery

- Bollinger R.D. 2004 “James Bond 007” – a tribute to 40+ years of the partnership, aged 16+ years on lees.

As someone wrote, Bollinger is a wine that wears its tuxedo in the dark, waits in silence, and knows exactly when to pop, but always with elegance.

Then our tour continued to Brimoncourt, whose headquarters is located in an old printing works “designed by Gustave Eiffel“. Let me quote Brimoncourt’s description of itself…

Inspired by the Regency spirit, Brimoncourt is a timeless and faithful tribute to the origin of champagne wine.

The House carries the values of elegance, sharing, independence and lightness.

Brimoncourt cultivates the fragile balance between modernity and tradition.

Passionate about history and fascinated by the tireless quest of men for excellence, admirer of nature, lover of the land of Champagne and its wine, Alexandre Cornot infuses this particular touch of personality and his almost obsessive requirement in each of the creations of the House he bought in 2008.

Brimoncourt is our timeless and faithful tribute to this history which carries us and whose cardinal values are elegance, sharing, independence and lightness.

The expression of our champagnes is always one of joyful elegance.

Before we look at their sparking wines, it’s worth noting that we were wonderfully well received.

Following a very complete introduction, we tasted their Champagne’s along with an impressive garden buffet of pâté-croûte champenois (served with the Cuvée Brut Régency), fish & seafood tartare (with the Cuvée Blanc de Blancs), Lobster & Asparagus (Cuvée Extra-Brut), hay-smoked poultry & morels (Cuvée Millésime MMIX), regional cheeses and red fruit tartlets (Cuvée Brut Rosé).

It’s important to understand that Brimoncourt is highly unusual both as a new Champagne house and in its market positioning.

Firstly, most Champagne houses are either centuries old or micro-grower startups. Brimoncourt is a revived brand (an historical name from the 19th century) relaunched in 2008, this puts it in a rare, if not unique, category.

Secondly, few new houses dare to enter Champagne unless they’re grower-producers. Brimoncourt is neither a large house nor a grower, but rather a negociant. They buy grapes and make wine under their own aesthetic vision.

Thirdly, the Champagne region is increasingly dominated by conglomerates (LVMH, Pernod Ricard, Vranken-Pommery), but Brimoncourt remains independent.

Fourthly, it’s rare to launch a brand of this scale and ambition outside the orbit of corporate funding or dynastic heritage.

So, it’s a “new” Champagne house with a focus on branding, ambition, and independence. It is neither a grower nor a Grandes Marques, so Brimoncourt is practically unique in 21st-century Champagne.

But Brimoncourt also goes one step further in the way it positions itself in the Champagne market. Some people call it anti-luxury luxury. Instead of the gold-and-black pomp of prestige cuvées, Brimoncourt uses clean design, pastel labels, witty messaging, and elegant minimalism. Its tone is lighter, more playful, less ceremonial. Where most houses evoke cathedral grandeur, Brimoncourt evokes gallery elegance.

It positions itself in art, design, and contemporary culture, not just wine world metrics. At times it’s more like a fashion house than a Champagne producer. The approach is radically different from the “legacy, tradition, savoir-faire” rhetoric typical in Champagne. Its focus is on the art-driven client who wants a design-led Champagne, which again is quite unique.

So who is behind Brimoncourt? Alexandre Cornot was born in Reims, son of an Air Force officer, he initially trained as a naval officer, briefly working in law, and as an art dealer (including at Christie’s New York).

Not hidden, but less well known, is that Cornot co‑founded Brimoncourt with Arnaud Dupuis‑Testenoire, who reportedly made his money in the steel industry. It is written that he made the initial investment (estimated around €5 million) and would also have helped secure further investors. We also know that in early years (circa 2013), Brimoncourt raised around €1.5 million, followed by another €2–3 million later that year. This was probably from a mix of private individuals backing the business in small to mid‑size investment rounds.

Already In 2006, the entity “SAS Champagne Brimoncourt” was registered as a legal structure by Cornot, perhaps in anticipation of acquiring the Brimoncourt brand, or with the hope that it could eventually be secured.

SAS stands for “Société par Actions Simplifiée“, which is a type of French legal entity, similar to a Simplified Joint Stock Company. It is a flexible, limited liability, corporate structure under French law for startups and partnerships with multiple shareholders.

In 2008, Cornot acquired the dormant Brimoncourt brand, and he brought in Dupuis‑Testenoire as a full partner.

Under French law someone can legally create a company under a name even if they don’t (yet) own the rights to the trademarked brand or historical name. It’s almost certain that Cornot must have known that the name “Brimoncourt” was not actively trademarked or defended at that point, i.e. it may have been in a dormant or lapsed status. That allowed a company to be formed using it as a legal name, while still needing to secure trademark rights separately before using it commercially (e.g. on bottles, labels, packaging, etc.).

The original Brimoncourt Champagne dates back to the mid‑19th century, though exact founding dates are unclear. It produced sparkling wines until ceasing activity in the 1950s. After that, the brand name remained dormant, unused in commerce for several decades. Ownership of the brand during its original operation is not well documented publicly. It likely belonged to a small local Champagne family or négociant. After the house stopped producing, the trademark lapsed or was unused. Original Brimoncourt wines were likely produced in or near Aÿ, typical for regional négociants of that era. However, no publicly available vineyard or facility details survive, reinforcing the idea that Brimoncourt rapidly became a defunct label.

Once purchased, they had the rights to revive it. Public sources do not disclose the exact amount paid for the brand. As a “sleeping” name the acquisition likely involved a modest trademark transaction.

Immediately Brmoncourt secured grape contracts (starting in 2009), launched its wines, and began full-scale commercial operations. 2010 was Brimoncourt’s first full production year, yielding around 65,000 bottles. From that, they began gradually building their family of wines, for example, the vintage Blanc de Blancs 2008 appeared in 2013.

Along with a brand and bottles, they needed a brand hub, e.g. offices, store rooms, and a tasting/event space.

Sometime in 2009–2010, after acquiring the label, they found a 3,000 square-metre site with a printing-house building (said to be built in part by Eiffel). It was repurposed as Brimoncourt’s HQ (offices, creative workshops, wine storage, and tasting/event spaces). There are no public figures on the price paid. Given the heritage classification, its sizeable footprint, and central Champagne location, the transaction may have been in the low‑to‑mid seven-figure range (this remains speculative in absence of official disclosure).

It’s mentioned that Brimoncourt has a distribution agreement with Baron Philippe de Rothschild in France, but they are not listed as a shareholder.

Another name hidden in a few of the secondary sources, is François Huré. He is a respected French oenologist and the Cellar Master (Chef de Cave) known for emphasising freshness, elegance, and terroir expression. He was named one of the Top 100 Master Winemakers by The Drinks Business in 2023. He studied biology at the University of Reims and later earned a National Diploma in Oenology (Diplôme National d’Œnologue) from the University of Burgundy. He then worked at the Domaine de Montille and the Hospices de Beaune, then followed a period at Coldstream Hills (Australia) and Pegasus Bay (New Zealand). He returned to Champagne in 2005, taking charge of the family estate Huré Frères in Ludes, before joining Brimoncourt in 2008 as its chief oenologist, overseeing the sourcing, production methods, and final blending.

As far as I can tell the Chardonnay comes from Côte des Blancs and Sézannais (notably premier and grand-cru zones), and the Pinot Noir/Meunier from Montagne de Reims (especially Aÿ) and the Marne Valley. This would usually be, but not always, through multi-year agreements to ensure grape quality, consistency, and traceability. However, there does exist a Champagne “bourse aux vins” which is a spot market for grape musts, base wines, or even bottled reserve wine. It’s used more for gap-filling or market responsiveness, but is less reliable for maintaining a house style.

There is also a mention that Brimoncourt’s wines are pressed, fermented, and aged in cellars “once used” by G.H. Mumm and Bollinger.

I remembering hearing that Brimoncourt produced around 250,000 bottles (not sure if this figure is annually), but only employs 10 people. This highlights the important role of totally outsourced harvesting, production and storage.

Let us turn our attention for a moment to the 19th-century printing works, now home to Champagne Brimoncourt. There is a statement attributing it (or part of it) to Gustave Eiffel, based upon architectural style and historical context.

What can we discover in online public records? Of course private records or records not available online, can alter considerably our understanding of the building.

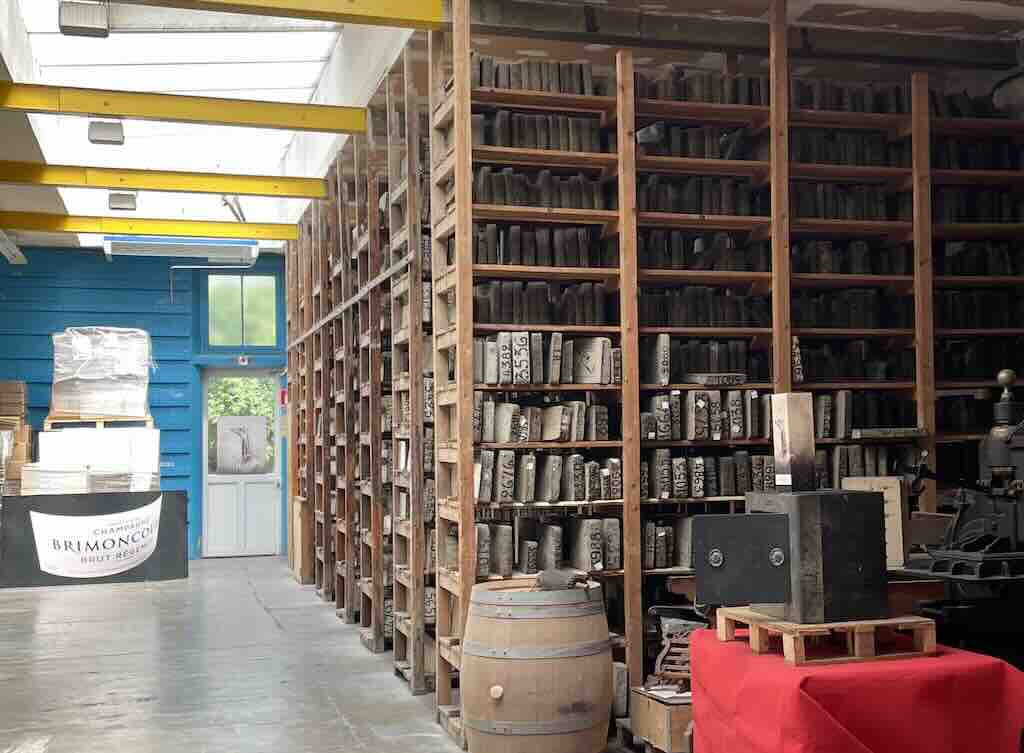

However, the most compelling fact is the unique archive of lithography stones (see above).

We know from online public records that a commercial printing works, known in legal registries as Imprimerie Édouard Plantet or simply Imprimerie E. Plantet, and classified under “autre imprimerie (labeur)”, installed itself in 1883 on the site of a former gendarmerie. There are no online public records indicating when the original building was constructed, who designed and built it, or why the gendarmerie moved, and where it moved to.

We know that in the mid-2000s, the “imprimerie” provided services like photocopying, reprography, binding, engraving, and production of stamps and printed materials. We also know that a SARL (Société à Responsabilité Limitée, the equivalent of a private company limited by shares) was created in April 2008 with a capital of €100,000. It took over the legacy of “Imprimerie E. Plantet – Maison fondée en 1883“, succeeding the previous company Imprimerie Billet in Aÿ. I’ve not been able to determine what this “succeeding” actually meant. However, Imprimerie Billet is a historic, family-operated, century old, print specialist located in Damery, near Aÿ. It is a world leader in Champagne labels, producing around 300 million labels annually and holding over 30% of the Champagne market share.

So we know that Imprimerie Édouard Plantet was legally active as a SARL between 2008-2011, when in December 2011 it was dissolved, and a secondary establishment was formed.

The mention of a “secondary establishment” usually refers, in French legal terms, to a secondary location of business operations (établissement secondaire) registered under another active company, not a new company per se. The “secondary establishment” most likely refers to Brimoncourt’s registration of a business presence at that same address shortly after the dissolution of the Plantet entity.

In May 2012 the SARL was declared “cessation of payments”, and entered judicial liquidation. In 2014 it was struck off the trade register due to asset insufficiency. And we know that Alexandre Cornot held the position of liquidator beginning in March 2010.

Wednesday 11 June

The day started with a drive to visit the oldest wine house in Champagne, Gosset, founded in 1584 by Pierre Gosset.

This was particularly interesting. Before COVID our preferred Champagne was a rosé from Perrier‑Jouët. When we started to drink Champagne everyday during COVID lockdown we noticed a slight change in the bottle shape made in 2020. I know it sounds stupid, but I found the new bottle less elegant looking. More importantly we had already noticed from 2013 onwards that the Perrier‑Jouët Rosé was slightly less vibrant than in the past. In fact, 2013 marked a clear shift, with a Pinot Noir increasing up to 55%, and Chardonnay dropping to 45%. My wife still liked the fruitiness, but I was less convinced (even if I’m a fan of Pinot Noir). This shift in ratio reflected a broader trend in prestige rosé Champagne, with more producers leaning into Pinot Noir to give their rosé depth and ageing potential. We should also not ignore the fact that rising temperatures have made it easier to ripen Pinot Noir fully, especially in cooler sites like Aÿ, Verzy, and Mailly, where Perrier‑Jouët sources their grapes. In any case drinking more than 60 different Champagnes during COVID gave us the opportunity to change to Gosset Rosé, which then became my wife’s preferred Champagne.

Pierre Gosset, born in 1484, was a prominent figure in the Champagne region. He was the Lord and Alderman of Aÿ, and he established a négociant business in 1584. This would mark the inception of what would later become Champagne Gosset, the oldest wine house in Champagne.

In the 16th century, the wines of Aÿ, primarily still reds made from Pinot Noir, were highly esteemed and often served at the tables of French royalty. Pierre Gosset’s wines were among these, competing with the renowned wines of Beaune (the wine capital of Burgundy).

The Gosset family’s dedication to winemaking spanned 16 generations, maintaining a focus on quality and tradition. In the 18th century, as the production of sparkling wines gained popularity in the region, the family naturally transitioned to producing Champagne. In 1760, Jean Gosset introduced the distinctive “Flacon Antique” bottle, featuring a unique necklace medallion, still used today.

It is my understanding that the original version of the slender “antique bottle” first appeared with Jean Gosset, ca. 1760. The bottle fell out of regular use after wartime disruptions, but later Gosset made the conscious decision to bring the antique bottle “back to life” and make it the emblem of their entire Champagne range. I’m not sure if Gosset practices the idea, but I’m told that the glass was often thicker and sometimes even included visible air bubbles or imperfections, mimicking hand-blown styles. It’s even said that the shape can influence how the Champagne matures on lees. Anyway, the bottles are visually striking.

The family did not always concentrate on wine production, for example Alphonse Gosset (1835–1914), a direct family member, was a prolific architect in Reims. He designed the Grand Théâtre, the post office, Bourse, churches, workers’ housing, and even the Pommery cellars. His son, Pol Gosset, continued the legacy, creating notable buildings across Reims, Épernay, Paris, and even Morocco.

Between 1959 and 1969, Champagne Gosset was official supplier to the Presidency of the French Republic under Charles de Gaulle.

The story goes that after over 400 years and those 16 generations of family ownership, Gosset looked for a partner that would first protect the estate’s heritage and identity, and also have the resources to boost its production and thus expand its reputation. The transaction was made with the Renaud‑Cointreau group, a French family-owned spirits conglomerate most famous for Cointreau liqueur and the little known but well respected Cognac Frapin. The Renaud‑Cointreau family was seen as a fitting choice due to shared values around quality, tradition, and a careful approach to growth.

It’s worth mentioning that the Renaud‑Cointreau family’s private wealth, accumulated through Rémy Martin and Cointreau, enabled them to invest in Gosset in 1993. This was independent from the publicly traded Rémy Cointreau company. The family simply chose to keep Gosset within their exclusive family estate, preserving autonomy and tradition.

The transaction was private, and no official amount has been documented in open sources. This is not uncommon for family business transactions of this nature, which are often kept confidential. But we can try a guess. Firstly Gosset was probably producing around 400,000–500,000 bottles per year in the early 1990s. It had a very good reputation but was undercapitalised, and its distribution was mostly French/European, not global. In 1987 Krug was bought by Rémy Martin for around $60-80 million (its now owned by LVMH), and in 1998 Deutz (producing around 1 million bottles annually) was bought by Louis Roederer for about $30-40 million.

Today, Champagne Gosset is still committed to traditional winemaking techniques, including avoiding malolactic fermentation to preserve the natural fruitiness and freshness of the wines. However, the wine still is double-fermented, and sits on the ‘lees,’ or dead yeast cells, absorbing proteins that help to create a wine with delicate smaller bubbles that make the desired “mousse”.

This last paragraph is often seen in brochures, etc., but what does it mean exactly? Basically there are two processes, with and without malolactic fermentation (called MLF for simplicity).

In both processes grapes are picked and gently pressed. Juice is clarified and prepared for fermentation. Yeast converts sugar into alcohol, producing a dry base wine (“vin clair”). This dry base wine is the work of the yeast (usually Saccharomyces cerevisiae) which converts sugar (glucose and fructose in grape juice) into ethanol (alcohol), carbon dioxide, aromatic byproducts (esters, alcohols, acids, etc.), and heat. The key is to control the temperature to control the process and protect the aromatics.

Champagne Gosset is not a grower, instead, it operates as a négociant-manipulant (NM). It sources the first pressing of grapes from across the region, primarily from Grande & Premier Cru villages in the Marne, Côte des Blancs, and Montagne de Reims, covering about 140 hectares of vineyards.

That said, Gosset’s roots do come from its own vineyard holdings. When founded in 1584, Pierre Gosset produced still red wine from grapes grown on his own Aÿ vines. However, in modern times, the house blends fruit from many crus instead of relying on estate vineyards.

So Gosset controls its sourcing and only selects first-pressings from around 160 grower-partners. That broad sourcing is how they maintain consistent style and quality year after year.

It’s my understanding that Gosset has a few hectares of estate-owned vineyards in Aÿ, plus a 2 ha domaine in Épernay used for hosting and very limited winemaking.

Now the processes (or techniques) diverge. To provoke (or encourage) malolactic fermentation (MLF) in Champagne or any still wine, winemakers take specific steps to create the right environment for lactic acid bacteria to convert malic acid into lactic acid. The malic acid is a natural acid present in grapes, but we must remember its the yeast that converts the sugar in the grape into alcohol. Malic acid is an acid, not a sugar, so it cannot be fermented into alcohol. Only sugars are converted into ethanol. To convert malic acid into lactic acid a bacteria (Oenococcus oeni) is needed. But it is temperature-sensitive, so winemakers typically keep the wine at 18–22 °C to activate MLF. They also need to ensure free sulphur dioxide levels <10–15 mg/l, which is low enough to allow bacterial activity. It is possible to count on the bacteria already present in the wine, cellar, or barrels, but it’s less predicable. Or the winemaker adds a starter culture, usually immediately after alcoholic fermentation is complete. This ensures a controlled, efficient conversion of malic to lactic acid.

In very simple terms this fermentation process take 2 to 6 weeks, depending on temperature, pH, alcohol content, and bacterial population, and converts malic acid (tart) into lactic acid (smooth). Experts talk about this process as making the wine more creamy and adding “buttery notes”, as opposed to a “crisper” wine with more acid. The MLF will only stop when the malic acid has been completely converted, and winemakers will have to stabilise the wine with sulphur dioxide and cold treatment to prevent unwanted bacterial activity later.

Gosset wants to preserve the freshness, and that means carefully selecting ripe but naturally acidic grapes (not underripe and too sharp, not overripe and lacking freshness). Remember, they can’t use MLF to “fix” sharp wines later. In fact they will act positively to stop any possibility of MLF. So they will cool the wine after primary fermentation to inhibit bacteria (e.g. <15 °C). They will also add higher levels of sulphur dioxide early to suppress any natural lactic acid bacteria.

But now Gosset must build roundness another way. This means that they will blend in older reserve wines aged in steel tanks (or for some select wines neutral oak). These older wines add texture, savouriness, and mature aromas (but without the creaminess from MLF). The aim is to find a fresh-based harmony without sacrificing acidity.

Both processes involve blending (assemblage). This means wines from different grape varieties, vineyards, and years are blended. Reserve wines (from previous years) add complexity. Non-MLF wines are blended more carefully to avoid harshness from excess acidity, so this may require using older reserve wines.

As far as I know Gosset sources its grapes from a very wide area (far wider than most other houses). It gets its Pinot Noir from Montagne de Reims, including Aÿ (the historic home of the Gosset family). The Chardonnay comes from Côte des Blancs, and the Meunier (with some Pinot Noir) comes from the Vallée de la Marne. Each grape from each region is supposed to deliver a different component to the blend, i.e. Pinot Noir gives structure, red fruit and ageing power, Chardonnay give minerality and citrus, and Meunier adds roundness and fruit.

Gosset also differs in the use of the different reserve wines in the blending. Firstly on average the reserve wines for blending are around 6 years old, but can exceed 20 years old. Houses that use MLF also blend with reserve wines, ranging in age from 3 years (Pol Roger) to 10 years old (Bollinger). As far as I know Gosset stores the reserve wines in stainless steel vats to keep the freshness and avoid oxidation. Gosset is also unusual in using only a limited quantity of reserve wines 12-15% in their non-vintage cuvées. Some houses can use in excess of 50% reserve wines. Also Gosset differs from many other houses in the different percentage of grapes used in the blend. Gosset uses a lot more Chardonnay (30-60%) and Pinot Noir (40-60%), and less Meunier (0-25%). By comparison Bollinger uses ~60%, ~25%, and ~15%, respectively, whilst Pol Roger uses ~33%, ~33%, ~33% respectively.

Both processes include a second fermentation in the bottle (Méthode Champenoise). A liqueur de tirage (sugar + yeast) is added before bottling, allowing in-bottle fermentation and carbonation (carbon dioxide). The bottles are sealed with a temporary crown cap. Little known is the use of a “bidule”. It’s a tiny plastic cup or insert placed inside the neck of the bottle during bottling. It sits under the crown cap and is used only during the second fermentation and lees ageing phase. During disgorgement, the bidule and sediment are expelled together (usually via freezing the neck).

Both processes leave the bottles to age “on their lees“ (dead yeast) for months or years. In both cases this builds complexity and refines the mousse (bubbles). However, the aim is a little different, with MLF it adds creaminess to an already-soft wine, and without MLF it softens the sharp acid over time (but this takes longer).

Again here, Gosset is different from many of the other houses. They will leave bottles to age up to 10 years or more, as compared to 5-7 years for many of the other Champagne houses.

In both processes (MLF and non-MLF) the bottles are riddled to collect lees in the neck, then disgorged (lees removed). Dosage (a mixture of sugar and wine) is added to balance acidity, often a little more for MLF wines to round off any sharpness. Gosset does not need to “mask” harshness because the wines are aged long enough to develop natural balance.

While the Champagne house itself is ancient, its current cellars are located in Épernay, not in Aÿ. These cellars are relatively new for Gosset, but have deep historical roots in the region. Gosset moved into these cellars in 2009, but the site was formerly of Champagne Perrier-Jouët and included its 18th-century chalk cellars.

Very poetic, our preferred rosé from Gosset, actually replaced our previous preference, the rosé from Perrier-Jouët.

The cellars we see above are dug into the chalk hillside and reach depths of up to 20 meters. They cover around 1.7 hectares of underground space, allowing the storage of 2.5 to 3 million bottles. The advantage of chalk cellars is that they offer a naturally stable temperature (10–12°C) and high humidity, ideal for long lees ageing.

Above we can see the bottles stored, and “tagged” with a rather cryptic notice.

The board tracks a specific lot of 105,000 bottles of Champagne, laid down on 7 July 2021, likely a specific blend (coded 221C1S), stored in a matrix of 250 × 420 bottles. The codes are internal to Gosset but reflect vintage, cuvée, and storage specifics. This is part of the méthode champenoise ageing process, and where the bottles undergo long lees ageing in Gosset’s chalk cellars in Épernay.

The 250 x 420 actually means 250 wire cages, each filled with 420 horizontally stacked bottles. The metal ageing cages (called gyropalette cages or sur lattes racks), hold the champagne bottles during the long ageing period en bouteille.

The word gyropalette needs explaining.

In the méthode champenoise (traditional method), after the second fermentation in the bottle, dead yeast cells (lees) settle in the bottle. These must be gathered into the neck of the bottle before disgorgement, where they’re removed.

Traditionally, this was done by hand. Firstly the bottles were placed on pupitres (wooden A-frame racks). Then they were rotated at regular intervals by “riddlers” (called remueurs), who would rotate and tilt each bottle slightly every day, over weeks, to coax the lees into the neck.

A gyropalette automates this process. It’s a large metal cage that holds a large number of bottles horizontally. The cage is then mounted on a mechanical base with hydraulic arms. The arms rotate and tilt cage and its bottles at programmed intervals and angles, mimicking hand riddling.

I understand that all aging, riddling, disgorging, and bottle storage now takes place in Épernay. However, some pressing and vinification may still occur in Aÿ, particularly for prestige cuvées.

What are we looking at above? Whilst the cellars are more or less totally dedicated to storing and ageing full bottles, the small space seen above actually performs one of the most important steps in creating Champagne.

Starting centre-right we can see firstly the disgorging machine (dégorgeuse), which freezes the neck, pops the temporary cap (the “bidule“), and ejects the frozen lees. Then comes the dosage machine which adds the liqueur d’expédition (dosage mixture of wine and sugar). And finally there is the corking and wiring machine, which inserts corks and fits the muselets (wire cages).

Let’s back-track and think about what this process does to the wine in the bottle. The second fermentation (prise de mousse) has occurred in the sealed bottle. Sugar and yeast were added at bottling (the liqueur de tirage), and the yeast has consumed the sugar and produced carbon dioxide, which has dissolves into the wine. The pressure in the bottle is typically 5.5 to 6.0 bar (or atmospheres). That’s about 2–3 times the pressure in a car tire, and it’s the reason why Champagne bottles must be made of thick, reinforced glass.

Disgorgement removes the yeast sediment (lees) that collected in the bottle neck during riddling. The bottle is opened very briefly after the neck has been flash-frozen, forming a plug of frozen wine and lees. So there will be a momentary drop in pressure when the bottle is opened. However, because the wine is very cold (often near 0°C), the pressure drop is minimal and short-lived.

During dosage, a small amount of wine (often the same Champagne) and sugar is added to replace the lost volume. This does not increase the pressure inside the bottle, it just fills the “headspace” and replaces the disgorged wine. It does not add new bubbles, they were already created during the secondary fermentation. What it does do is add a touch of additional sweetness (depending on style, Brut, Extra Brut, etc.). It can be a tiny flavour tweak if the wine is taken from a special base wine or old reserve wine. So it aims to add to the mouthfeel, balance, and aging trajectory, but does not add any addition “fizz”.

So the final pressure in the bottle remains about 5.5–6.0 bar at cellar temperature. And it stays like that, until the cork is “popped”.

Above we can see five different wines from Gosset. I think the normal tasting involved the first four, but (I think) due to the questions, etc., the host brought out the 2012 vintage “Celebris” as well.

Celebris is Latin for, “celebrated”, “renowned”, or “famous”.

The question was about what exactly does more or less ageing really add to the overall taste of a Champagne, and did one to two extra years really make that much difference. What was clear was that, independently of a persons likes and dislikes, there was a distinct different is appearance, aroma and taste.

Gosset is our (my) favourite (at least for the moment), and so I’m going to try to cover all the key features of each wine…

Brut Excellence – the house entry-level non-vintage brut cuvée

- Label colour: Deep red (light silver neck foil)

- Appearance: Light gold, steady bubbles

- Aroma: Green apple, white flowers, light toast

- Taste: Fresh, approachable, balanced citrus and brioche

- ~€40–€45

- Note: This wine is still available, but no longer appears on the Gosset website (it was still in our tasting group)

Grande Réserve Brut – Signature house style, non-vintage brut, Pinot Noir more dominant

- Label colour: Dark red/maroon (gold neck foil)

- Appearance: Golden straw, fine mousse

- Aroma: Pear, hazelnut, honey

- Taste: Richer, structured, with depth and a long finish

- ~€45–€60

Grand Blanc de Blancs – 100% Chardonnay, aged 4+ years

- Label colour: Light blue

- Appearance: Bright pale gold

- Aroma: Lemon, white peach, chalk

- Taste: Elegant, mineral-driven, saline and fresh

- ~€75–€85

Grand Rosé Brut – Chardonnay (50%-60%) and Pinot Noir

- Label colour: Pink-gold or pale salmon

- Appearance: Pale pink with copper hues

- Aroma: Raspberry, rose, citrus

- Taste: Refined, crisp, with fresh red fruit and finesse

-

~€65–€75 retail

Celebris Extra Brut (Vintage) – Top-tier Champagne, aged (up to 10 years), no added sugar

- Label colour: Black with gold text (Blanc de Blancs) or black-gold (Rosé)

- Appearance: Pale gold with fine, persistent bubbles

- Aroma: Brioche, dried fruits, citrus zest

- Taste: Dry, elegant, layered with mineral and toasted notes

- ~€210–€325 for Celebris Blanc de Blancs 2012

- ~€170–€230 for Celebris Rosé 2008

One noticeable difference between the photo of our tasting, and the Gosset website, is that we see mention of a year (vintage), whilst on the website there is only a mention of ageing duration (e.g. 12 years).

Gosset wants to reinforces a house-driven narrative of style and long ageing over year-to-year differences. And it also avoids a direct comparisons with more “vintage-labeled” producers (e.g. Bollinger, Louis Roederer, etc.).

French Champagne terminology

Viticulture & Harvest

- Côte – A slope or hillside, often part of vineyard names (e.g. Côte des Blancs).

- Clos – A walled vineyard (e.g. Clos du Mesnil).

- Pressurage – The act of pressing grapes, extremely regulated in Champagne.

- Marcs – The official term for a press load of grapes in Champagne (4,000 kg max).

- Cuvée – The first, highest-quality juice (about 2,050 liters from a marc).

- Taille – The second pressing, lower in acid and quality (up to 500 liters).

Winemaking

- Débourbage – Juice clarification before fermentation.

- Vin clair – The still base wine, before secondary fermentation.

- Assemblage – The blending of different base wines (from different crus, grape varieties, or vintages).

- Tirage – The bottling of the blended wine with sugar and yeast to induce second fermentation.

- Liqueur de tirage – Mixture of sugar and yeast added before tirage.

- Prise de mousse – The “foam taking” — the second fermentation in bottle that produces the bubbles.

Aging, Riddling, and Disgorgement

- Sur lattes – Bottles stored on their sides during aging.

- Remuage – Riddling: gradually tilting and rotating bottles to collect sediment in the neck.

- Pupitre – The traditional wooden A-frame rack used for remuage.

- Gyropalette – A modern machine that automates riddling.

- Degorgement (à la volée/à la glace) – Removal of the sediment plug; manually (volée) or by freezing (glace).

- Liqueur d’expédition – The dosage: a mixture of wine and sugar added after disgorgement.