In April 2002 Monique and I bought a painting of “Plum Blossoms in Snow” in Beijing.

It is about 2 metres by 1 metre, and we brought it back home in a roll tube, and later had it framed. It has hung over our bed since then, and always brings back fond memories, e.g. my wife loved the strong pinks and reds.

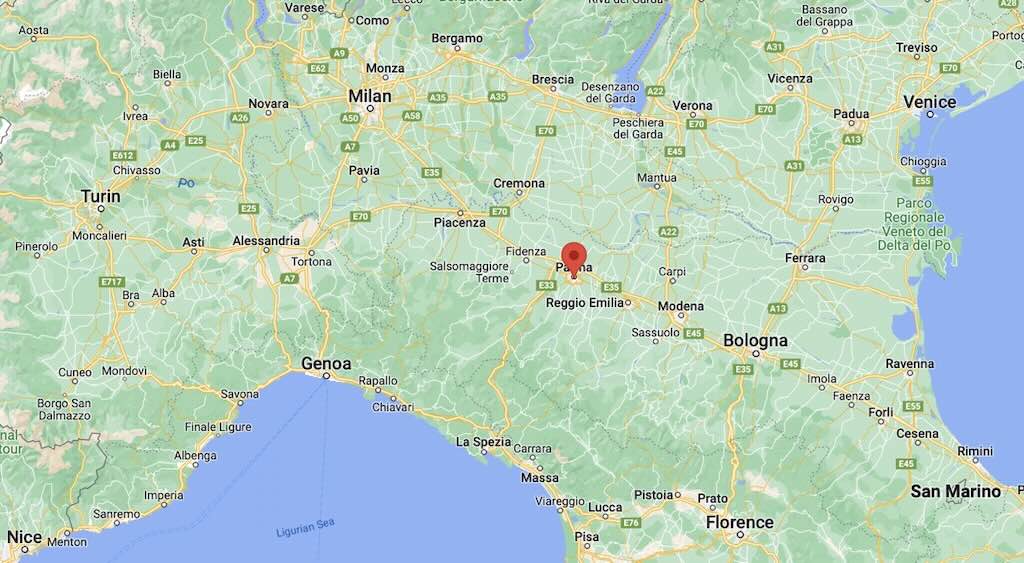

I was on an official visit, and my wife and I were very well received during our stay in Beijing. I don’t remember the exact context, but we were accompanied by someone from the Chinese Ministry of Culture to an officially endorsed studio. I remember well the studio itself. There was no “front shop” that I could see, and the interior was very dusty and surrounded by old looking storage racks holding what looked like a multitude of paintings all rolled up. There were a few tables, one or two with what looked like unfinished paintings, and there were a few small scrolls hanging vertically. It certainly didn’t look like a “tourist” studio, and the they appeared a little surprised to see us, but I think they knew our chaperone.

The studio was probably a member of the Chinese Artists Association (中国美术家协会) or the Chinese Calligraphers Association (中国书法家协会). I understood that the visit was to see a kind of “living tradition”, but it was Monique who decided she would like to take something back with her.

Initially we viewed a number of smaller pieces, but Monique was looking for something more imposing. This was usually not her style, but she wanted a big display piece (we were still living in a big house with lots of wall space).

She hit on a piece with an abundance of pinks and reds (two of her favourite colours). The plum blossom (梅花, méihuā) is China National “spiritual” flower, and today the peony (牡丹, mǔdān) is China’s national flower (more specifically the tree peony Paeonia suffruticosa). The plum blossom embodies endurance in adversity, purity, and renewal. I remember the official looking very pleased, and saying it was a very wise choice, and that it would bring much peace and tranquility to our home.

My wife did receive a written certificate, but I have never found it. I know I paid $200 and the painting was carefully rolled and placed into a very solid looking tube and sealed. I suspect that the official I was with mediated a price that appeared to satisfy both myself and the elderly man in the studio. I might add, it cost more than $200 to frame it back home.

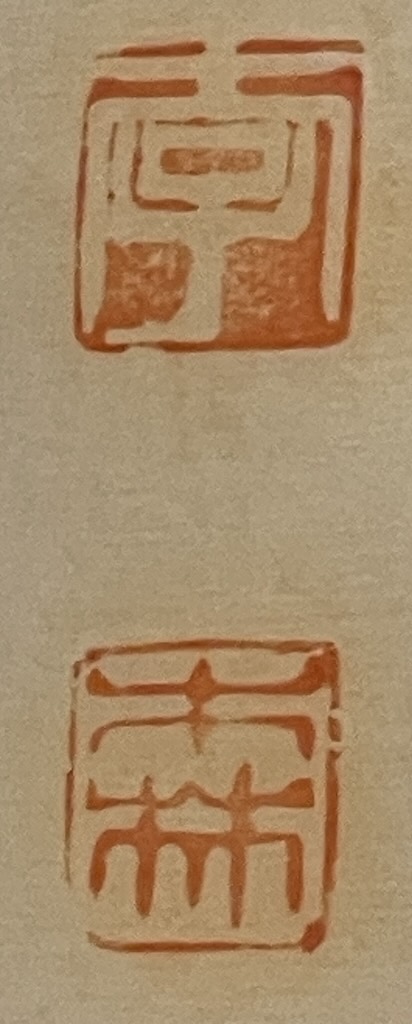

雪斋 (Snow Studio) and 草堂 (Thatched Hall)

There is an inscription 雪斋 (Snow Studio), which appears to match the art name of 溥伒 / 溥雪斋 (Pu Jin).

The seals read 草堂 (Thatched Hall), which also appears to match one of the artists known halls/studios 松风草堂 (Pine Wind Thatched Hall). The “草堂” portion is well known, and it is plausible that it could be used in isolation on a seal.

The style of plum blossoms and poetic inscription fits the tradition in which the artist worked. And his presence in Beijing art circles lends credibility to having a studio accessible to official or cultural visits.

However the artist is said to have died or disappeared around 1966. So our painting might be a more modern reproduction, possibly executed by a descendant or inheritor adopting the artists studio name.

Studio names and art names are sometimes reused, but snow, plum and the “thatched hall” motifs are classical and may appear in names of other, lesser-known artists or studios. The seal on this painting is just 草堂, without a modifier like 松风草堂, which might suggest a simpler or alternative hall name, or an artist using the core “thatched hall” phrase.

Given the coincidence of 雪斋 in the inscription, 草堂 as seal, and his historical use of 松风草堂, it’s possible that this painting is by someone in the artists lineage or school who adopted his studio name or tradition. It is equally possible that it could be a later production by someone carrying on his “studio” name, or even a homage piece.

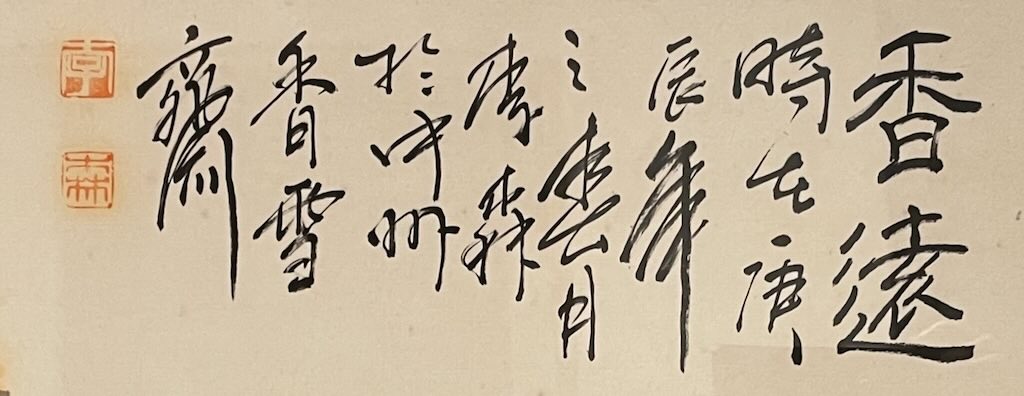

The Inscription

The inscription reads (simplified transcription):

香远时自清,雪香齐

With the seals and brush style, it looks like a couplet or poetic line. A reasonable interpretation is:

香远时自清 (xiāng yuǎn shí zì qīng)

The fragrance travels far, naturally pure.

雪香齐 (xuě xiāng qí)

Fragrance joins with the snow.

This is a very classical type of inscription, evoking the idea that even in the harshest winter, the plum blossom’s fragrance carries far, untainted, and in harmony with snow. This is a metaphor for upright character and integrity in difficult times.

The 香远 (xiāng yuǎn) is composed of 香 (fragrance) and 远 (far), and together form “fragrance travels far”. This phrase is actually part of a famous couplet attributed to Song dynasty scholar Lin Bu (林逋, 967–1028)…

疏影横斜水清浅,暗香浮动月黄昏

“Sparse shadows slant across clear shallow water; hidden fragrance drifts in the yellow dusk of the moon”

The idea is that plum blossoms emit fragrance that lingers and carries, subtle but enduring.

The idea that “its fragrance travels far, and at all times it is naturally pure”, is a moral metaphor, meaning a gentleman of integrity is like the plum, upright and incorruptible, and his virtue apparent even from afar.

Later the brushwork is more fluid, and appears to read…雪香齐 (xuě xiāng qí). This links plum blossoms with snow fragrance (i.e. with snow’s purity). It is a poetic way of saying “the purity of plum fragrance stands equal to the purity of snow”.

Next two larger characters stand out…雪斋 (Xuě Zhāi), or 雪 meaning snow and 齋 meaning studio, study, hermitage. This is very likely the artist’s studio name “Snow Studio”. It’s thought that this would match the seals “草堂” (Thatched Hall) as a parallel or secondary studio designation.

Overall Impression

This is a traditional Chinese ink-and-colour painting of plum blossoms 梅花 (méihuā). Plum blossoms are one of the most important motifs in Chinese art and poetry. The idea is that they bloom in late winter and early spring, often before the snow has melted, and therefore symbolise resilience, endurance, and renewal.

The trunk and branches are painted in bold, dark ink strokes, suggesting age, strength, and vitality.

The blossoms in pink, red and dark-orange stand in sharp contrast, creating vibrancy and life against the more austere branches.

The composition is classical, with twisted old branches filling the canvas with clusters of flowers, suggesting strength enduring through hardship.

This type of work is often referred to as “ink-and-wash with added colour” (水墨加彩), a technique developed in the Chinese academic painting tradition.

However, the picture field is densely packed with blossom clusters across much of the span, with a few heavy, inked trunks/major branches running diagonally and then fanning into a web of twigs.

Negative space is limited. Traditional plum compositions usually breathe through voids (large reserves of paper) and what is called a “three-mass structure” (e.g. root-joint-crown) with clear directional flow. Here the centre of mass feels overcrowded, and blossom density is too uniform, producing a decorative “wallpaper” effect rather than a sense of depth and natural growth. Several twig lines create tangents and near-parallels that flatten the image.

The reality is that the painting looks more like a studio “show” piece scaled up for effect, rather than a traditional composition.

Major branches are laid in with consistent, wet black, and the articulation of nodes/knuckles are generalised and not individualised. Secondary twigs sometimes thicken or hold the same width as they move outwards towards the viewer. Normally the thickness should thin down decisively from old wood, to secondary wood, to new twigs. Angles are too crisp and economical. The branch logic isn’t strict, with a few “Y-forks” look symmetrical, and some twigs meander rather than “snap” with calligraphic intention. The trunk ink lacks dry–wet modulation and “flying white” that suggests bark. All this suggests that the brush strokes were carried with a fairly uniform load. The expert eye would argue that the strokes come from the bone rather than the muscle and don’t have the “authority” of a master.

Blossoms are mostly flat pink/red dabs, with limited differentiation between bud, half-open, and full-open. Calyx/stamens are understated or missing. Good dotting (点) and drawing (勾) you demonstrate varied growth and budding stages, some flowers with clear calyx structure and a few precise stamens to attract the eye. Here, many flowers are just uniform disks, and the cluster-to-cluster rhythm is repetitive.

So the painting is pretty from a distance but a little monotone close up. A master would have spent far more time on the uniqueness (character) of the individual flowers.

The pinks are bright and even, but the transitions are shallow, with red/pink often sits atop ink without mixing. The colour looks a little too “synthetic and clean”, which is common style for the late 20th century. There’s little colour and intensity modulation inside the petals, so they don’t look like individual and uniquely different flowers. Trunks are largely single-tone black so no “atmospheric ink” to push some branches into the background.

Overall, the painting aims at decorative appeal (and “someone who loves pink”).

The calligraphy lacks “structural tension” in the curves and turns. The characters are a bit too even and mild. Perfectly correct but not compelling.

The pair of seals are generic hall titles without a personal name reinforces the sense of a workshop identity. They communicates lineage more than authorship.

Finally, it worth noting that upscaling a painting to mural size often exposes weak brush grammar and repetitive flower dotting.

The result is pleasing viewed from 3–4 meters, but doesn’t reward close reading.

Contemporary Beijing studio painting (plum blossoms), ink and colour on paper, signed with studio names “Snow Studio” and “Thatched Hall”.

Perfectly respectable, but not the work of a major hand. It is not a tourist “export scroll”, but an authentic studio piece, painted by someone with training and credentials.

For my wife and I, it is not just plum blossoms, but a memory of early-21st century Beijing, still oscillating between pride in tradition and the practical needs of the modern marketplace. It now sits above my bed, as a daily reminder of our 49 years spent together.